Navigating Market Inefficiencies (Dec 2024)

In everyday life, people love prices that are out of sync with fundamentals. Homebuyers celebrate free equity when the appraisal comes in above the contracted purchase price. Thrift store shoppers look for bargains, digging through racks and bins of clothes and household goods, celebrating when they find a heavily discounted designer bag or pair of shoes, or a set of antique dishware. People clip coupons, shop sales, and take advantage of accidental disconnects—like in 2022, when a gas station owner in Tennessee made a typo when setting the pumps, making gas $0.45/gallon instead of $4.50. It took 5 hours for a customer to point out the error.

We have long found it interesting that the approach in the investing world is very different from everyday life—namely, many investors aren’t interested in bargain hunting. In fact, the opposite is true: paying up for assumed growth is de rigeur in today’s markets. U.S. markets and big technology companies trade at sky-high valuations, whether the fundamentals justify it or not.

We have written and spoken frequently (in our recent optionality webinar and whitepaper) about how markets are inefficient, and the different ways in which our process is designed to take advantage of those inefficiencies. This whitepaper takes a step back to ask the “why” and “what” questions—why do these inefficiencies exist, and what should investors do to take advantage of them?

Where in the world is homo economicus?

Market inefficiencies exist because market participants are an emotional species. This statement was not always accepted. In the 1970s, social scientists believed that people were generally rational, made logical decisions, and that fear, affection, and/or hatred explained most of the occasions when people departed from rationality. The rational man theory was effectively debunked in 1979 by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who demonstrated that people departed from rationality much more frequently than believed at the time. Their work describes two distinct systems of thinking: System 1 (which operates automatically, relying on intuition and emotion, and requires little-to-no conscious effort), and System 2 (which is based on reason and involves slow, analytical, logical thinking that requires conscious mental effort and control). They defined numerous heuristics (mental shortcuts) and biases that influence our decisions. Since Kahneman and Tversky first articulated prospect theory, homo economicus has abdicated the throne to homo irrationali.

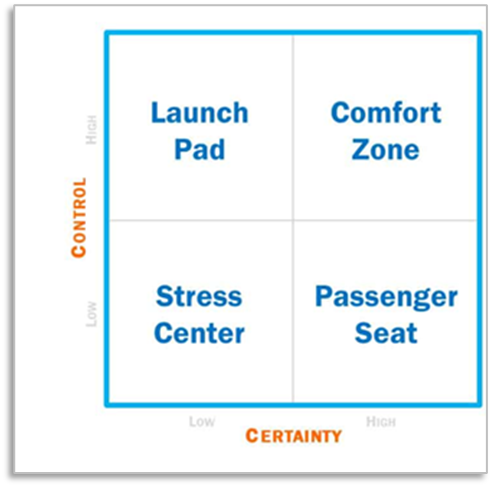

In the decades that followed their initial findings, studies have shown that intuition and emotion are additional drivers of decisions, which is the subject of Peter Atwater’s book The Confidence Map (2023). Atwater’s visual representation of the emotional framework behind decision making is useful for understanding why optionality can become so mispriced.

Atwater’s thesis is that our decisions are influenced by emotion (few would argue with that), and emotion is generally driven by two variables: perceived certainty and perceived control. The far-right corner of the confidence quadrant—the Comfort Zone—is just that: a place where we are comfortable, where things feel familiar. In a high certainty, high-control environment, people are optimistic about the future. They think they will be successful at whatever it is they are undertaking. In the Comfort Zone, caution goes out the window, and the decisions we make reflect our unshakable confidence in the status quo. As Atwater puts it:

The more confident we feel, the more rose-tinted our glasses, and the less apt we are to go looking for or put stock in counter arguments. We limit our view to belief-affirming evidence…. At our very peak in confidence, we believe those feelings will be permanent. What marks the top—whether for a market, a sports team, or a leader—is the extreme extrapolation of invulnerability. We believe we will stay unscathed forever. Not surprisingly, not only does our accompanying behavior look ridiculous in hindsight, it naturally sets up the precipitous collapse in confidence that follows thereafter…

That precipitous collapse as reality sets in leads us to the opposite of the Comfort Zone: the Stress Center, where we feel powerless with our lack of control and overwhelmed by the uncertainty of the situation. In the Stress Center, we feel vulnerable, anxious, and pessimistic. Here, people aren’t thinking about the future. As Atwater says, this is “Here. Me. Now.” It is easy to see how these two extreme quadrants play out in the markets. Investors are overly confident at the peaks, relying on System 1 thinking; similarly, they are overly pessimistic in the troughs. In both cases, investors are unable to conceptualize a future that is different from the present.

Atwater’s other two quadrants, the Launch Pad and the Passenger Seat, are not comfortable places. We like it when we feel like we have both high certainty and control, hate when we have neither, and are anxious when we have one and not the other. In the Passenger Seat, we have high certainty but low control; in other words, we have ceded control to someone or something—getting a haircut or being on an elevator are examples. We like it when we have ceded control voluntarily and we are okay in the passenger seat if we have high certainty that things will turn out well. People get on airplanes assuming they will land safely.

In the Launch Pad, there is high control but little certainty. Like the Passenger Seat, this is not a comfortable place to be. Behavioral economists have shown that people abhor uncertainty. But whether investors accept it or not, the Launch Pad is where they must live. The future is unknown and unknowable. The best we can do is mitigate the risks of an uncertain future by controlling the portfolio management decisions we make.

Opportunities arise when investors forget that investing often happens in the Launch Pad. Today, U.S. investors are hugging the right side of the Comfort Zone and Passenger Seat; they have a high degree of certainty in the future. Investors with high certainty tend to suspend System 2 thinking—the slow, deliberate, logical thought processes that result in the most considered decision-making. There is excitement about the future (and an assumption that things will continue as they are, especially regarding artificial intelligence and technology). Unfortunately, this is a very dangerous thing for investors—feeling good about the future doesn’t change the fact that we can never know what is going to happen.

We believe it is one of our competitive advantages that, when other investors may find themselves in the Comfort Zone, Passenger Seat, or Stress Center, we stay firmly in the Launch Pad. We want to buy from those in the Stress Center and sell to those in the Comfort Zone and/or Passenger Seat. As Warren Buffet said, “be fearful when others are greedy, and greedy when others are fearful.” John Maynard Keynes believed that most investors would rather lose money from the safety of the herd than stray out on their own. This mindset allows those who embrace uncertainty to use it to their advantage. If we have lemons, we should make lemonade; if we feel wind, we should construct windmills; if we are making decisions about an uncertain future, we should build an anti-fragile portfolio. Before delving into a logical approach to dealing with dangerously inefficient markets, let’s touch on portfolio fragility.

Inefficient markets demand anti-fragility.

“Wind extinguishes a candle and energizes fire.”

-Nassim Taleb

“The fragile wants tranquility, the antifragile grows from disorder,

and the robust doesn’t care too much.”

-Nassim Taleb

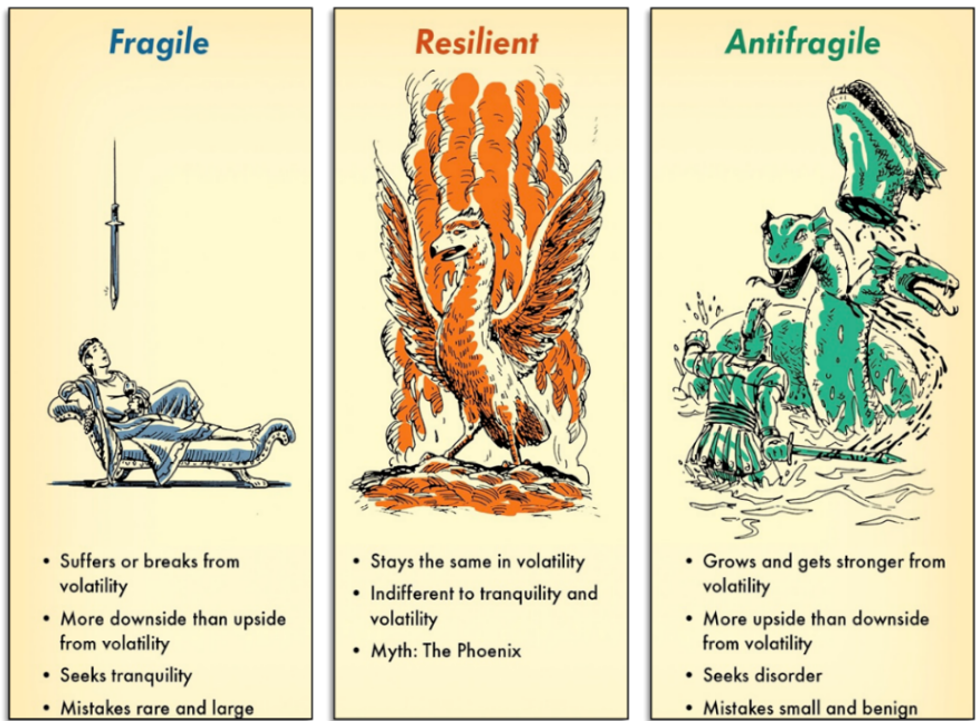

There are some things in life that thrive and improve with randomness and uncertainty. That is the subject of Nassim Taleb’s book Antifragile: Things that Gain from Disorder (2012). Antifragility, positive asymmetry, positive optionality—these terms all suggest that the downside is limited, and upside is outsized (the opposite of fragility and negative optionality). Taleb draws on mythology to illustrate his framework:

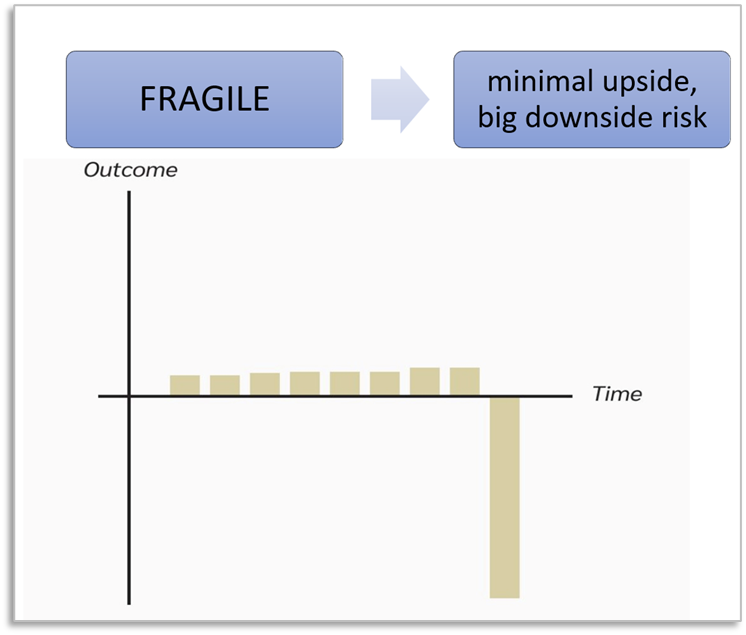

Fragility: The Sword of Damocles

King Dionysius was extremely rich and powerful—and also extremely unhappy. Damocles, a courtier, pesters Dionysius until Dionysius offers to let him hold the throne so he can see for himself how wonderful it is. Damocles sits on a golden couch clothed in resplendent garments, waited on hand and foot by many servants, and given all the rich food, drink, and perfumes he could want. But then, Damocles notices that Dionysius has placed a sword above his head, held in place by nothing other than a single strand of horsehair. Clearly, a fragile situation. The upside (riches and power) is more than offset by the downside (nearly certain death). If the status quo persists, Damocles will be fine. But if there is any disorder and the horsehair breaks, the outlook is very bleak.

Fragile systems thus, like the status quo, hate volatility, and have much more downside than upside. A typical fragile payoff diagram looks as such:

Perhaps this sounds like our current economy? U.S. GDP growth has been strong, but it has been propped up by an unsustainable amount of debt. If there is a landing—even a soft one—does the horsehair break?

Resiliency: The Phoenix

The phoenix is a mythical creature; a magical bird with bright, gorgeous colors, it is associated with fire, shapeshifting, and healing. When it is killed, the phoenix disintegrates into ashes, from which it is then reborn. The phoenix is the very definition of resiliency—neutral to change and volatility and recovering from adversity without trouble.

The closest economic analog to the phoenix, in our opinion, is a short-term U.S. treasury. It has low duration risk and is at least generating some yield to protect from inflation (although we would argue not enough—a topic for another time). Thus, at least in the short-term, these securities are neutral: in a downturn, they don’t lose; in an upturn, they don’t gain.

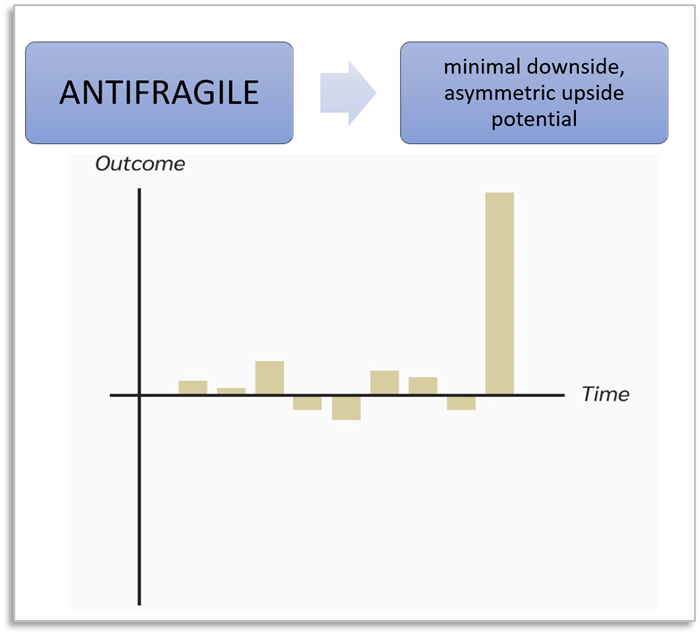

Antifragility: The Hydra

In Greek mythology, the hydra is a multi-headed serpent that guards the underworld. Hercules battles the hydra, attempting to cut off its head; however, for every head he cuts off, two more heads grow in its place. The hydra grows stronger as it is challenged.

An antifragile system is one that likes disruptive events and uses those events to rebuild and grow beyond its original state. Like the hydra, antifragile things thrive on disruption, becoming stronger. They love randomness and uncertainty. Antifragile systems have little downside should the status quo continue, but asymmetrically more upside should things change. Notice how the antifragile payoff diagram below is opposite of the fragile payoff diagram shown above:

In our optionality whitepaper, we made the case that anti-fragile portfolios are those with asymmetric upside and limited downside, and optionality is found in the places where markets are inefficient. But to find inefficiencies, and capitalize on that optionality, investors must look for them. Which brings us to our final point…

Active management matters in inefficient markets.

“An enthusiastic philosopher, of whose name we are not informed, had constructed a very satisfactory theory on some subject or other, and was not a little proud of it. ‘But the facts, my dear fellow,’ said his friend, ‘the facts do not agree with your theory.’

‘Don’t they?’ replied the philosopher, shrugging his shoulders…’then, so much the worse for the facts!”

-Charles Mackay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

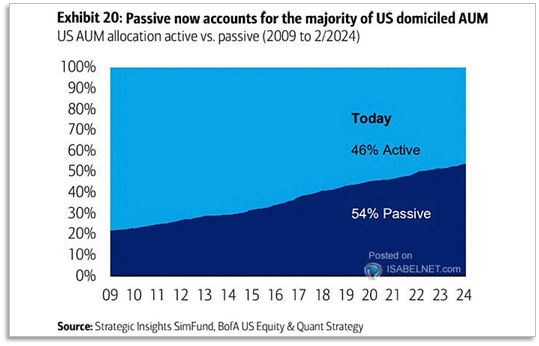

We would argue that investors have ceded control of portfolio management to the whims of asset flows; more than half of assets under management are being passively managed, as the chart below shows. Investors have willingly ceded control of what companies they own, in what proportion they own them, and at what price.

Total holdings of U.S. ETF assets recently reached $10 trillion for the first time in history, and the market has more than doubled over the last 5 years. U.S. ETFs now account for 71% of the $14 trillion global ETF market. While numerically, 57% of ETFs are passively managed, assets under management tell a different story: less than 8% of total ETF assets are actively managed, according to Morningstar.

Passive investing relies on the assumption that markets are efficient—without that assumption, passive investing would not be possible. And yet, the theory and practice of that hypothesis seem to diverge. It is one thing to believe that markets price in all available information. It is another to assume that the information is always accurate, and that those who act upon that information always practice rational decision making.

Centuries of speculation and financial bubbles are proof enough that this assumption is not true. Was Enron reporting accurate financial information? Was someone who paid 10,000 guilders (the cost of a mansion) for a tulip bulb acting rationally? Were those who paid millions of dollars for digital images in 2021 making measured decisions? We think not. Information is not always accurate, human beings are not always rational, and decision-making is not always measured. While at times the price of a stock may capture all available information, usually, it does not.

Passive vehicles that track indexes and depend on algorithms for decision-making simply cannot capture all the moving pieces of Mr. Market. Neither can active managers, for that matter—there are very few true informational edges. What there are, however, are analytical, behavioral, and organizational edges. Active managers who adhere to a disciplined process, demand large price discounts, and risk-adjust can address many of the issues that passive indexers face. Good companies and good ideas do not necessarily equal good investments, and thoroughly vetting every stock in a portfolio is one way to mitigate that risk.

At Kopernik, we believe that investors are best served by an active management style that uses fundamental bottom-up research to find the best values, risk-adjusts and demands large discounts to recognize those values, and utilizes opportunistic trims and adds to maximize the best portfolio returns.

We believe that there is a need for diligent investment research. We believe that there is an investment return on independent thought, on hard work, on willingness to bear the discomfort that goes hand in hand with contrarianism…The case for passive investing assumes just a few ‘passengers’ taking a free ride on the back of a market made ‘efficient’ by millions of investors working hard to gain equal access to information, staying rational at all times, performing analysis to derive a fair price, and always paying that fair price. Even if one were to believe that people are rational and that markets can be efficient, once there are too many passengers relative to too few drivers, the theory goes out the window. At that point, the premise is nullified; the tail is wagging the dog.

-Kopernik CIO Dave Iben, The Passenger (2016)

That does not mean that we are anti-passive investing; indeed, there are benefits to such an approach as part of a diversified investment portfolio. However, as we put it in 2016, the time to invest passively is when few are doing so. The markets are closer to efficiency when many are actively striving to discover fair pricing. When few are doing so, we prefer to be the driver instead of the passenger. Being the driver means that we are constantly analyzing the road ahead of us, and the traffic around us, identifying the market inefficiencies that we see and determining how to best navigate them. Doing so allows us to be good stewards of capital and, in our opinion, manage a portfolio that portends superior returns.

What has been the result of years of “price agnostic” passive investing? The highest (riskiest) levels ever for U.S. securities based on price to: GDP, book value, replacement value, revenues, and a host of other metrics. Howard Marks suggests that no one can predict the future, but they can make a solid, educated guess as to the proximate part of the cycle. Those in the “Launch Pad,” uncertain as to the future, can surmise that this is likely near the market peak, and is a-decade-and-a-half off the trough. Knowing that, they can, and should, divert the bulk of their funds out of harm’s way and toward undervalued sectors, industries, regions, countries, assets, and specific stocks.

As always, thank you for your continued support.

Dave Iben, CFA

CIO, Lead Portfolio Manager

Alissa Corcoran, CFA

Deputy CIO, Portfolio Manager, Director of Research

Mary Bracy

Managing Editor—Investment Communications

Important Information and Disclosures

The information presented herein is proprietary to Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is not to be reproduced in whole or in part or used for any purpose except as authorized by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell any product or service to which this information may relate.

This letter may contain forward-looking statements. Use of words such as “believe,” “intend,” “expect,” anticipate,” “project,” “estimate,” “predict,” “is confident,” “has confidence,” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are not historical facts and are based on current observations, beliefs, assumptions, expectations, estimates, and projections. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to risks, uncertainties and other factors, some of which are beyond our control and are difficult to predict. As a result, actual results could differ materially from those expressed, implied or forecasted in the forward-looking statements.

Please consider all risks carefully before investing. Investment strategies discussed are subject to certain risks such as market, investment style, interest rate, deflation, and illiquidity risk. Investments in small and mid-capitalization companies also involve greater risk and portfolio price volatility than investments in larger capitalization stocks. Investing in non-U.S. markets, including emerging and frontier markets, involves certain additional risks, including potential currency fluctuations and controls, restrictions on foreign investments, less governmental supervision and regulation, less liquidity, less disclosure, and the potential for market volatility, expropriation, confiscatory taxation, and social, economic and political instability. Investments in energy and natural resources companies are especially affected by developments in the commodities markets, the supply of and demand for specific resources, raw materials, products and services, the price of oil and gas, exploration and production spending, government regulation, economic conditions, international political developments, energy conservation efforts and the success of exploration projects.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. There can be no assurance that a strategy will achieve its stated objectives. Equity funds are subject generally to market, market sector, market liquidity, issuer, and investment style risks, among other factors, to varying degrees, all of which are more fully described in the fund’s prospectus. Investments in foreign securities may underperform and may be more volatile than comparable U.S. securities because of the risks involving foreign economies and markets, foreign political systems, foreign regulatory standards, foreign currencies and taxes. Investments in foreign and emerging markets present additional risks, such as increased volatility and lower trading volume.

The holdings discussed in this piece should not be considered recommendations to purchase or sell a particular security. It should not be assumed that securities bought or sold in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of the securities in a Kopernik portfolio. Kopernik and its clients as well as its related persons may (but do not necessarily) have financial interests in securities or issuers that are discussed.