South Korea (Jan 2025)

“Rose of Sharon, thousand miles of range and river land;

Guarded by her people, ever may Korea stand.”

-“Aegukga,” (애국가) South Korean national anthem (English translation)

The Rose of Sharon, or mugunghwa, has a long history in Korea. Its name means “eternal blossom that never fades,” and records show that it was treasured as a “blossom from heaven” starting in ancient times. The Silla Kingdom, a dynastic period that lasted from 57 BCE-935 CE, called itself Geungwahyang, meaning “Country of the mugunghwa.” The flower was planted as a symbol of resistance during the Japanese occupation (1910-1945), and adopted as the national flower after Korea regained its independence from Japan. It symbolizes the country’s beauty, resilience, and tenacity. Today, it appears in the South Korean national anthem (as quoted above), the presidential seal, and other national emblems.

It may seem a stretch to open an investing whitepaper with a botanical description, but national symbols are national symbols for a reason – they are part of the “imagining” that communities undertake when they are defining who they are. The image of a bald eagle soaring through the sky recalls the individual freedom, strength, and resilience valued by the American people; Rome’s Colosseum represents the enduring legacy of a great empire; and the mugunghwa signifies a country that has bloomed and flourished where it is planted.

We’ll come back to the Mugunghwa in a bit, but first, a brief introduction to this paper. With 18% of the Global All-Cap portfolio in South Korean stocks1, we wanted to share our views on the investment opportunities we are finding there. This whitepaper will first give a brief overview of the history of South Korea (especially its remarkable economic transformation since World War II), then will examine the current market and economic landscape before describing some of the specific investment opportunities that Kopernik is finding in the country.

From Authoritarianism to Democracy

“Democracy is not a gift from heaven; it must be achieved through struggle.”

-Kim Dae-jung (President of South Korea, 1998-2003)

On September 2, 1945, Japanese representatives surrendered to the Allied powers, bringing an end to the years of global conflagration wrought by World War II. For the then-unified Korea, this meant an end to 35 years of Japanese colonial domination – replaced by Allied postwar occupation. Arbitrary divisions were common in the postwar era (in Europe, a divided Berlin existed within a divided Germany). Korea was no exception, divided into two occupation zones along the 38th parallel: the Soviet Union occupied the North, and the United States the South. This division, originally planned to be temporary, became permanent at the end of the Korean War in 1953.

In 2025, the enduring legacy of this postwar partitioning is one of the most visible reminders of the Cold War that defined the geopolitical landscape in the second half of the twentieth century. The two Koreas would develop along radically different lines. North Korea (officially the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, or DPRK) is a Communist totalitarian dictatorship, a legacy of its close associations with both the Soviet Union and China during the Cold War. In contrast, South Korea (officially the Republic of Korea, or ROK), is today a constitutional democracy with a mixed economy.

It took many decades for South Korea’s democracy to develop; initially, the country was led by the autocratic nationalist Syngman Rhee. Rhee’s strong anti-communist leanings meant that he had support from the U.S., but his authoritarian policies led to a student uprising in 1960 that knocked him from power in favor of a short-lived parliamentary government. Weak and ineffective, that parliamentary system was overthrown in a military coup in 1961, and General Park Chung-Hee took power. Park’s rule lasted until his assassination in 1979 during a series of student protests.

Authoritarian rule continued with Park’s successors throughout the 1980s until 1987, when massive pro-democracy protests erupted following the death of a student activist. In October 1987, a new constitution was finalized, allowing for direct presidential elections, and strengthening the power of the National Assembly. 40 years after the partition, South Korea’s democracy was in place. As is increasingly common across the globe, political corruption remains significant in South Korea – almost every presidential administration has seen a large corruption scandal, and five of South Korea’s former presidents served or are serving prison sentences as a result.

Exports, Exports, Exports: The Miracle on the Han River

“We have been born into this land, charged with the historic mission of regenerating the nation.”

-Park Chung-Hee, 1968

Park’s economic philosophy focused on self-reliance. The Korean War had been devastating to South Korea’s economy: civilian casualties reached roughly 1.5 million; property destruction was estimated at $3.1 billion, with nearly 43% of residential homes and businesses destroyed. South Korea was heavily dependent on foreign aid, which totaled roughly $2.3 billion during the 1950s. The total assistance amount accounted for 74% of total government revenues between 1953-19612. Determined to reverse this, Park and his government instituted a series of Five-Year Plans to guide the country’s economic development.

The following 4 decades saw economic growth so strong the period became known as the “Miracle on the Han River.” South Korea’s economy completely transformed, going from a predominantly agricultural subsistence economy to a massive industrialized and technologically sophisticated export-based economy. Historians typically date the Industrial Revolution in Europe from 1760-1840: 80 years. South Korea’s transformation was half that long.

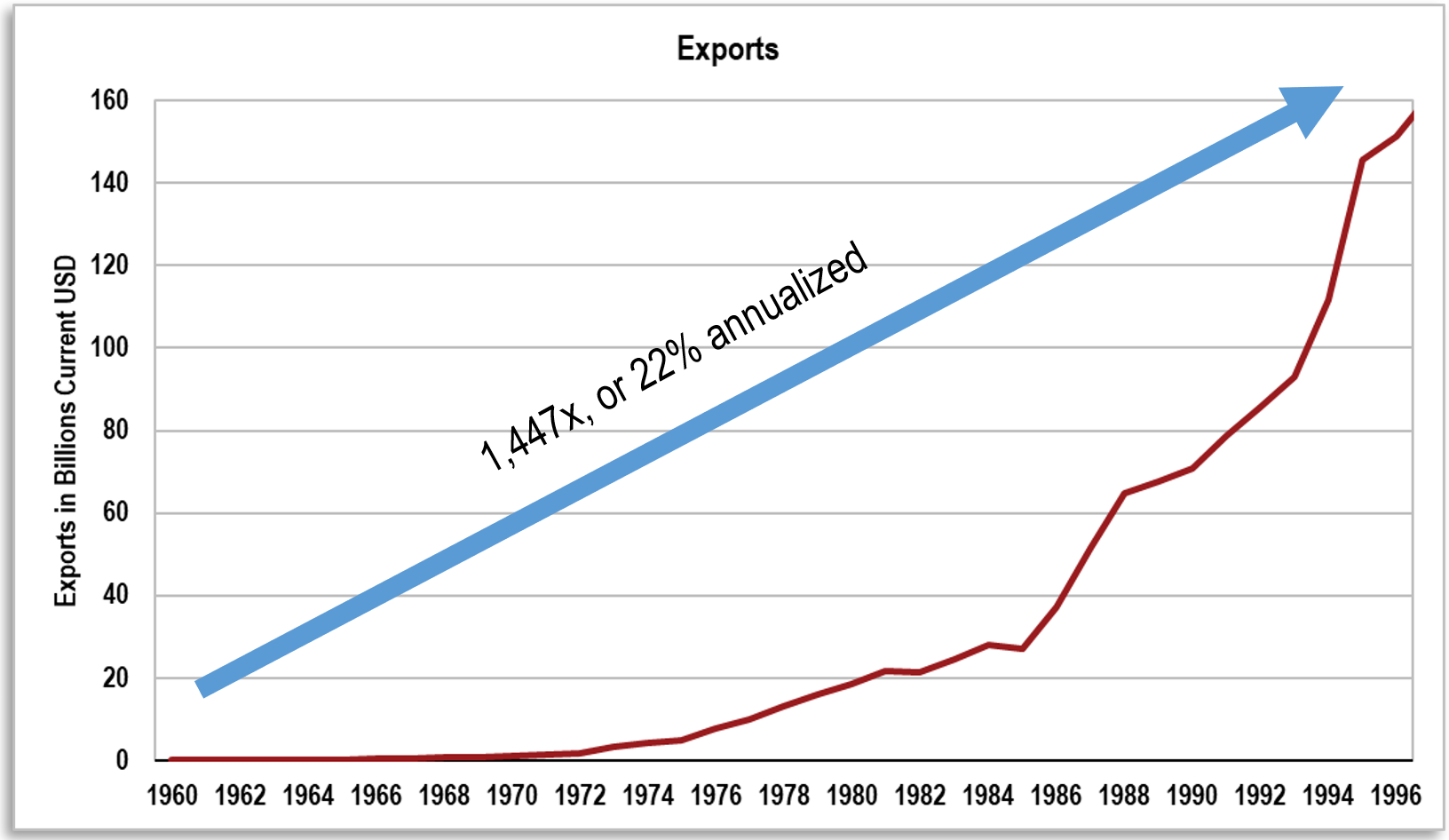

The bulk of this growth was driven by exports, which were a key focus of Park’s economic planning. The government implemented many strategies to boost exports as part of the Five-Year Plans, including the establishment of free trade zones and subsidizing key industries. Exports grew at a 22% annualized growth rate from 1960-1996:

Another component of this massive economic growth was the government’s support of the chaebols. Chaebols are industrial conglomerates that are run and controlled by an individual or family, and they dominate South Korea’s economic structure to this day. These chaebols are huge, consisting of multiple diversified affiliates, but control is centralized in the hands of a few.

Many of the chaebols trace their origins back to the immediate postwar years, when Korean businessmen obtained the assets of some of the Japanese firms. These companies had close links to the government of Syngman Rhee; many received preferential treatment in exchange for kickbacks. When Park came to power in 1961, he at first vowed to root out the corruption of this system but quickly changed his tune when he realized that the chaebols were necessary to achieving the sort of economic growth he desired. Chaebols were instrumental in the massive growth during the Miracle at the Han River, in large part because they were able to produce a multiplicity of goods, which was imperative as the country sought to diversify its exports. South Korea’s exports shifted as economic growth continued; while the dominant exports in the 1960s were textiles and wigs, the defense and chemicals industries were predominant by the 1980s, with electronics and technology coming to the fore in the 1990s.

On the brink of the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis, South Korea’s economy would have been unrecognizable to a time traveler shot forward from the end of the Korean war in 1953. Gone was the rural, agrarian system of the past; urbanization drove the population of Seoul from 1.3 million (in 1953) to 10.1 million (in 1996). Total exports had gone from $32 million in 1960 to $130 billion in 1996. GDP per capita had gone from $64.09 in 1953 to $13,403 in 1996. The tiger economy was roaring – what could possibly silence it? Of course, tigers cannot roar forever, and the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis knocked the wind out of the South Korean economy’s lungs. GDP growth halted and then reversed: 6.2% growth in 1997 became -5.1% in 1998. Unemployment tripled, and the won plummeted, reaching a record low of 1,995KRW to $1 USD. Of the 30 largest chaebols, 11 of them went bankrupt between 1997-1999. Korean banks had non-performing loans amounting to 118 trillion KRW (27% of GDP) as a result of over-lending, which was common before the crisis hit. The country, which had a large amount of short-term foreign debt and rapidly dwindling foreign exchange reserves, was on the brink of bankruptcy by November. An IMF bailout package – the largest in history at the time – lent South Korea $58 billion on the condition that the country raise interest rates, restructure the financial sector, and place limits on the chaebols. The economy rebounded quickly, and South Korea paid the loans back in full by 2001, well ahead of schedule. The entire country participated: the Gold Collection Campaign encouraged citizens to turn in their gold to help repay the IMF; 3.5 million citizens turned in 227 tons of gold coins, jewelry, and other trinkets, which were melted down to help repay the loan.

A poster from the Gold Collection Campaign. Note the mugunghwa on the bottom left.

For the last 25 years, economic development in South Korea has continued to be strong. GDP has more than tripled since 2001, and today it is the world’s 14th-largest economy, with a GDP (in PPP terms) larger than that of Spain, Canada, Australia, and the Netherlands. South Korea ranks higher than the U.S. in educational outcomes and life expectancy—while spending far less in both education and healthcare—and it has a lower poverty rate and lower budget deficit as a percentage of GDP than the U.S. does. As we have noted elsewhere, South Korea shares many characteristics of developed markets; indeed, the FTSE classifies it as such. Meanwhile, MSCI classifies it as an emerging market—and it appears that most investors agree with that characterization, given the enduring power of the “Korea Discount.”

Geopolitical Risk and the Korea Discount

“Fear is the foe of the faddist, but the friend of the fundamentalist.”

-Warren Buffet

In recent years, we have seen political instability increase around the world. According to the Carnegie Endowment’s Global Protest Tracker, more than 160 anti-government protests erupted in 20243. In the U.S., we were pleased to see that, for the first time in 3 election cycles, protests did not erupt in the streets over the results of November’s presidential election. France’s National Assembly voted to oust the prime minister in the first successful no confidence vote in over 60 years. Great Britain has seen four prime ministers in the last 5 years. And incumbents around the world have been losing elections: since 2022, more than 70% of incumbent leaders, parties, or coalitions in developed economies have lost control of the presidency or prime ministership.

In South Korea, this political instability reared its head early in December when President Yoon Suk Yeol declared an “emergency martial law,” the first since 1987. Yoon accused the opposition party of controlling parliament, conducting “anti-state” activities, and sympathizing with North Korea. The subsequent sequence of events was well-covered in international media: the National Assembly voted to reject the martial law declaration; Yoon, constitutionally obligated to abide by the Assembly’s vote, lifted martial law. Yoon has since been impeached, but the impeachment must be approved by the Constitutional Court (which has 180 days to decide). Prime Minister Han Duck-soo was appointed as Acting President, but (adding even more confusion) on December 27, 2024, he was also impeached. On January 15, 2025, President Yoon was arrested. We continue to monitor the situation.

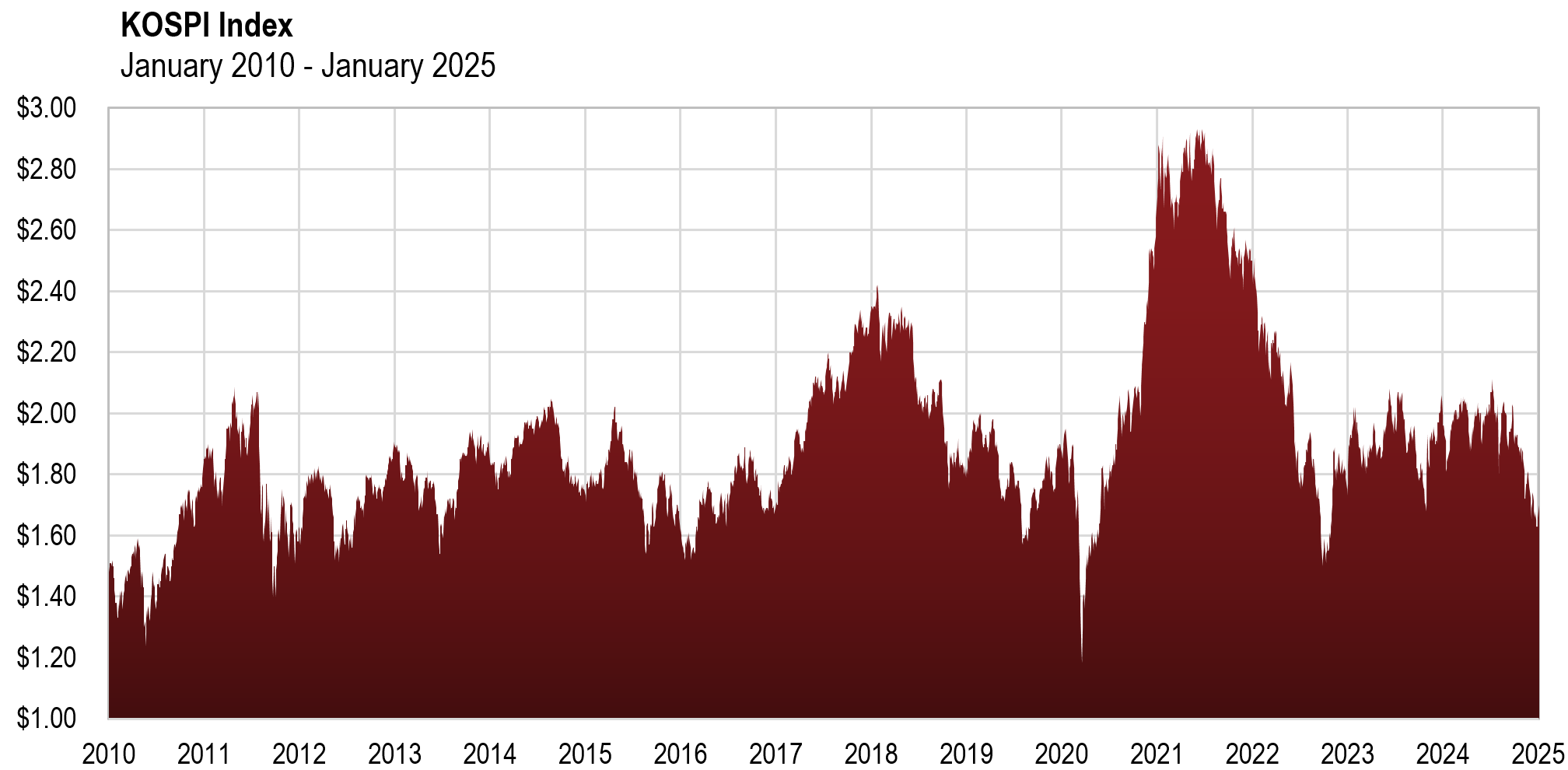

As we have seen numerous times around the globe, political uncertainty frequently (although not always) lends itself to market volatility. While many investors see volatility as risk, we believe that risk is the prospect of a permanent loss of capital or purchasing power. Indeed, the volatility wrought by political instability has frequently provided buying opportunities, which likely could be the case now – the KOSPI was down 21% in USD terms in 2024 (while the NASDAQ was up 29%!).

Geopolitical risks are present in every country and every region, and thus in every business. Managing these risks is not black and white. As fundamental bottom-up investors, we evaluate each company on a case-by-case basis. Mitigating risk for us means focusing on price, in addition to quality, only purchasing when a company’s valuation is trading below its risk-adjusted intrinsic value as determined by Kopernik, and diversifying the portfolio to account for the risks involved. Avoiding risk is impossible, whether we are investing in emerging or developed markets. Investors should demand to be overcompensated for taking the risk, thereby enabling positive investment outcomes to much more than offset the ill-fated ones.

In the United States, the market does not appear to be pricing in any risk, even in the face of contentious political debates, questionable fiscal policies, and an economic war with much of the world. In contrast, the South Korean market has more than priced in the risk. Stock prices are depressed due to the perception that emerging markets are riskier than developed ones and poor corporate governance practices among the chaebols, South Korean family-owned conglomerates. This “Korea discount” has persisted for many years and continues in the face of the government’s “Value Up” program, which was launched early in 2024 and is designed to encourage companies to voluntarily implement corporate governance improvements and minority shareholder-friendly policies. While we remain unconvinced of its ultimate effectiveness, it’s encouraging that we have seen some examples of companies making changes.

Investment Opportunities

“The time of maximum pessimism is the best time to buy,

and the time of maximum optimism is the best time to sell.”

-Sir John Templeton

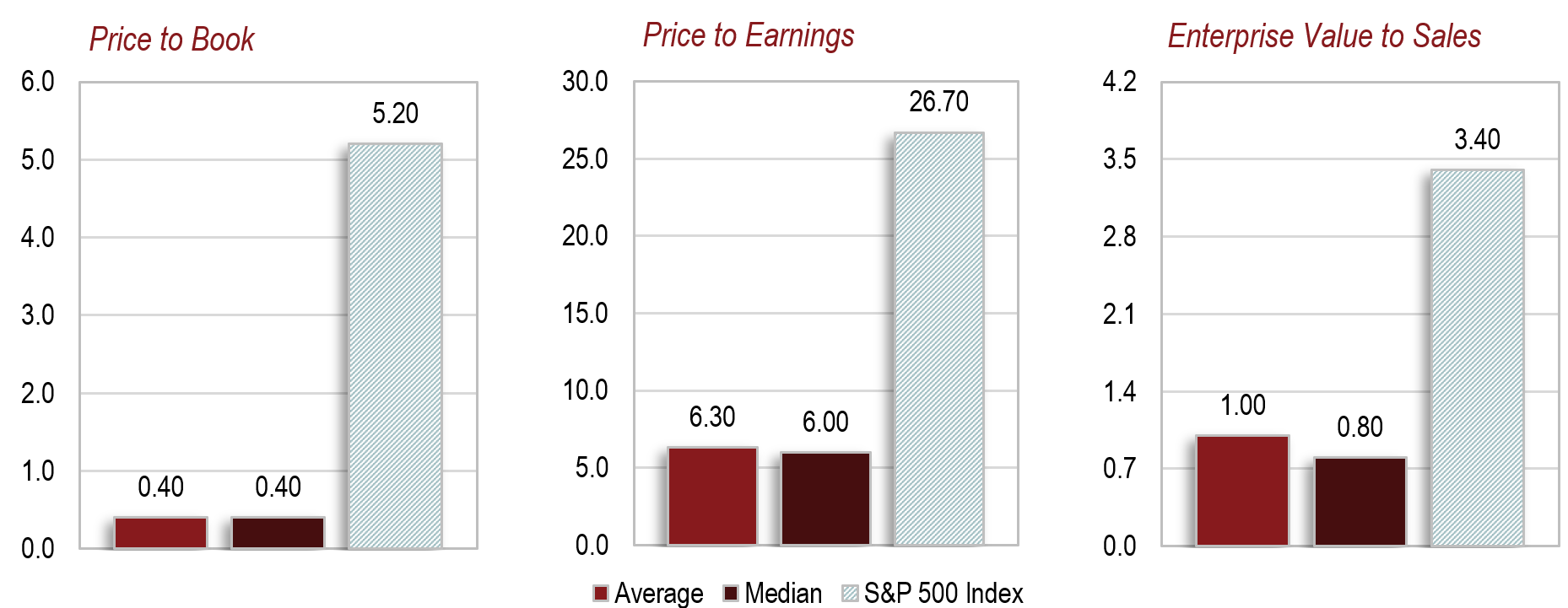

As mentioned above, we currently have a 18% weighting to South Korean stocks in the Global All-Cap portfolio4. As with everything in our strategies, this is a result of our fundamental bottom-up research process. Kopernik does not have target exposure levels, so the portfolio construction is a product of the opportunities our analysts are finding. The Korea discount has presented numerous opportunities for us to purchase high-quality, industry-leading franchises trading at deep discounts to their intrinsic values and developed market peers:

Kopernik Global All-Cap Strategy – South Korean Holdings

As of 1/6/2025

A few specific examples follow. We have discussed many of these in previous quarterly calls, but the discount is so pronounced that it’s worth summarizing here.

Telecom

South Korea is one of the most connected countries in the world in terms of mobile phone usage – 86% of the population owns a smartphone. The country has a triopoly of telecom companies that dominate the market; Kopernik has positions in two of them, KT Corp and LG Uplus Corp. KT Corp is the largest player in broadband/fixed line and the number two player in wireless; LG Uplus is the number three player in both. Both also have an internet-based television service. Combined, they have a 70% market share in wireless, 62% market share in broadband/fixed line, and a 68% market share in internet-based TV. Importantly, both underearn on margins, portending significant upside should margins converge to industry standards. These are dominant companies in a necessary industry—people will give up a lot of things before they give up their phones.

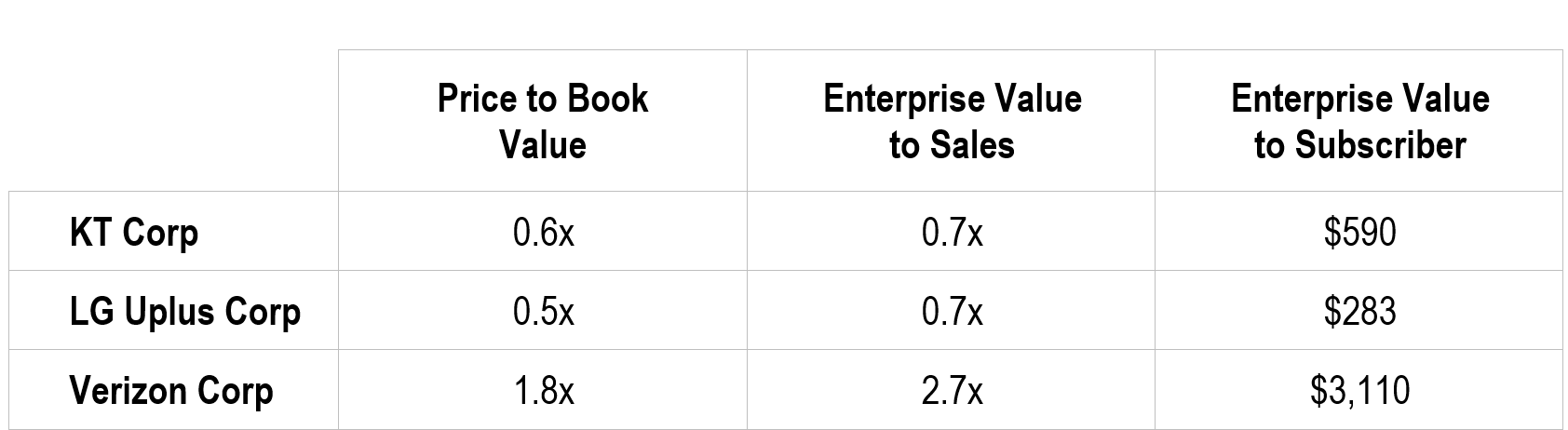

Dominant, and undervalued. Both KT Corp and LG Uplus trade for less than book value and are discounted on an EV/Sales basis. Both are also highly discounted compared to their U.S. peers, especially on an enterprise value to subscriber basis.

Kopernik has positions in KT Corp and LG Uplus Corp.

KT Corp’s stock price was up 20% in 2024, and the discount is still pronounced. The Korea discount is alive and well in telecom.

Retail

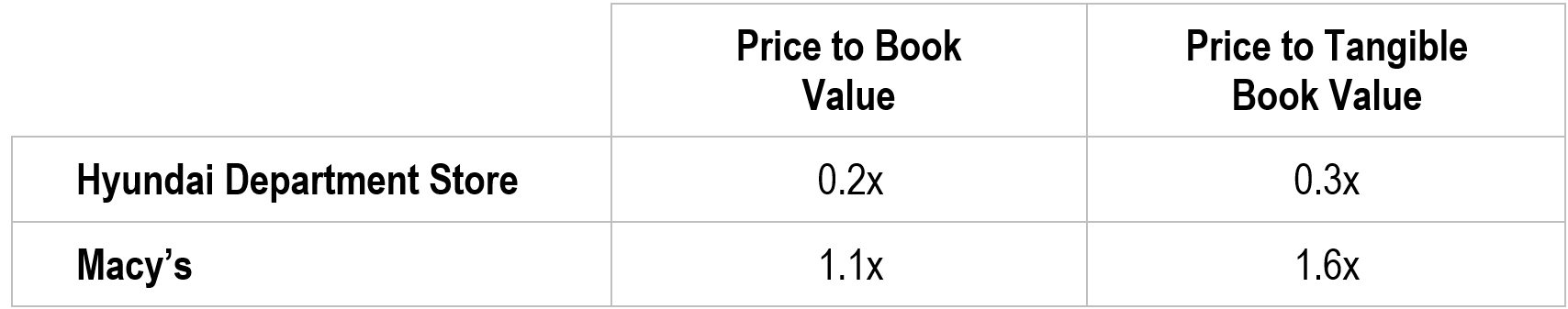

The department store is a dying breed in the United States; less so in South Korea, where department store sales made up 17% of retail sales in the first half of 2024. While in the U.S., the department store format is in structural decline, the format is favored in Korea – stores have strong foot traffic and are also viewed as hubs of social life and entertainment. Hyundai Department Store (HDS), one of three major department store brands in the country, trades at a fraction of Macy’s, on a price-to-book basis. HDS owns real estate in central Seoul, while Macy’s has a number of suburban locations where traffic is weak. The market has priced in negative sentiment in South Korea, less so in the U.S. HDS is significantly undervalued compared to Macy’s; it is also a business in better shape, in our analyst’s opinion.

Kopernik has a position in Hyundai Department Store.

Information Technology

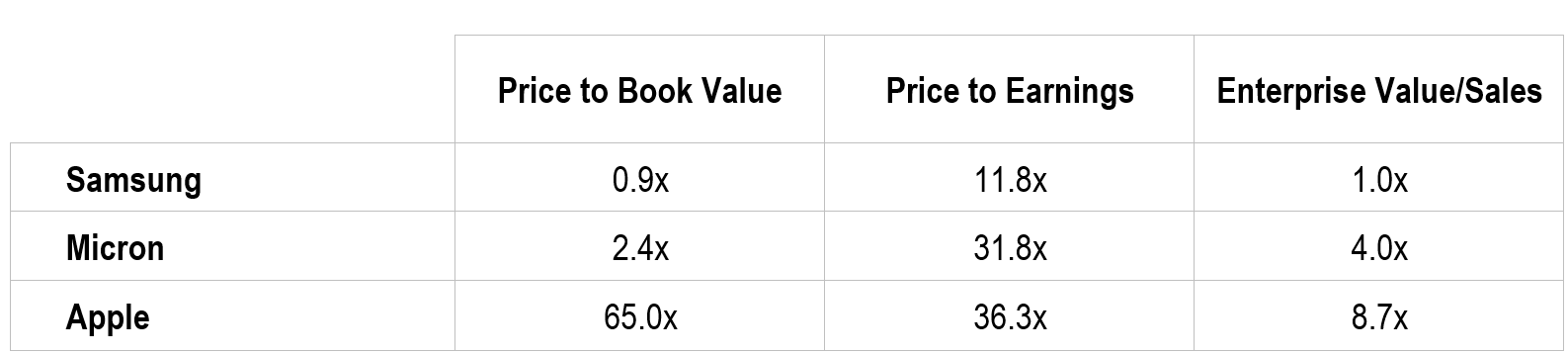

Combined, Apple and Samsung have roughly a 36% market share in the global smartphone market – Samsung’s 18.4% compared to Apple’s 18.1% (as of Q3 2024). Tablets are a slightly different story: Apple has a 39% market share, compared to Samsung’s 19%. Both companies are technological leaders in a competitive industry. Yet the difference in their valuation is pronounced:

And yes, Samsung has a significant memory chip business, so we added Micron to the table!

Samsung is a good example of how important the chaebols are to the South Korean economy; in 2022, the company’s revenue made up 22% of South Korea’s GDP, and it is set to account for half of the country’s economic growth in 20245. Another dominant company in a necessary industry – another example of the massive difference in price.

Conglomerates

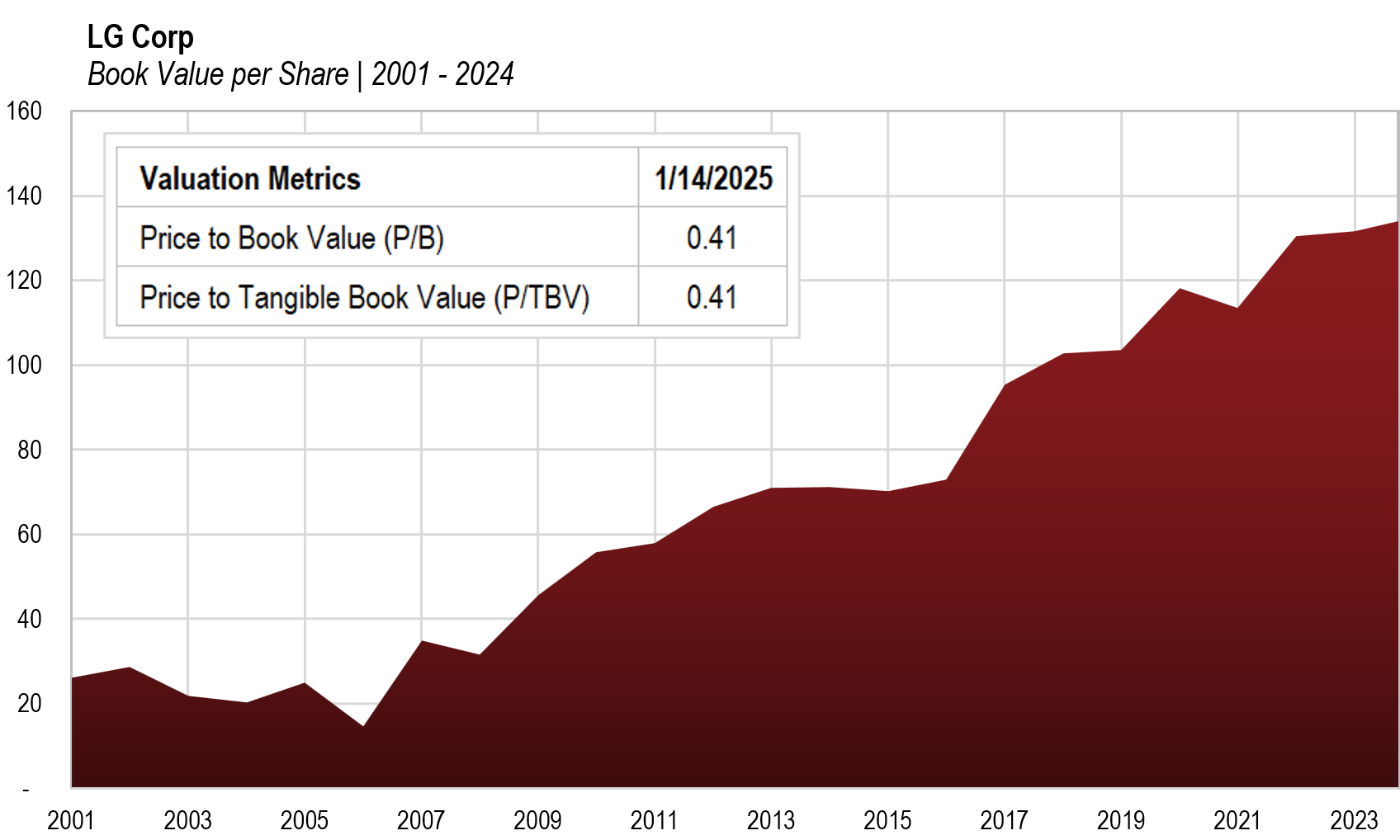

Conglomerates are complex and many investors shy away from them. There are significant issues: many conglomerates buy mediocre companies and overpay for acquisitions; misleading accounting methods can obfuscate analysis of them. As is usually the case, however, lumping all conglomerates in one basket is a mistake. As we discussed in our recent market inefficiencies whitepaper, active managers can take advantage of dislocations in the marketplace. In conglomerates, we are able to buy the “Berkshires of Asia.” While South Korean chaebols frequently have challenging governance practices, they also have heavy insider ownership and are aligned with the shareholder. LG Corp is one example. While the market sees a complicated company with a stagnant share price in a risky emerging market, we like the fact that it owns industry-leading businesses and has grown book value steadily for more than 20 years.

Kopernik has a position in LG Corp.

A Note on Mitigating Risk

Kopernik does not invest in governments. We invest in companies, and we risk adjust to account for uncertainties, including geopolitical risk, ESG risk, financial risk, and the potential for “black swan” events. On average, our investments in South Korea require a 50% discount to theoretical value. Many of these companies trade at prices that are further discounted to our estimates of their risk-adjusted intrinsic value.

A Mugunghwa Among Thorns?

“Some people grumble that roses have thorns; I am grateful that thorns have roses.”

– Alphonse Karr (French novelist, 1808-1890)

As promised, let’s return to the mugunghwa. The plant is a novice gardener’s dream: hardy and tenacious, it thrives in full sun with moisture but can tolerate partial shade and draught. It flourishes in multiple climates; according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, it can be grown in Zones 5-9, meaning it can flourish anywhere from western Montana to central Florida. It’s easy to see why a country that has seen periods of colonial domination, war, and authoritarian government would utilize it as a national symbol: it thrives where it’s planted.

In some ways, investors can look at South Korea as a mugunghwa among thorns (for the purposes of my analogy, we’ll ignore that the mugunghwa is actually a member of the hyacinth family!). The phrase “a rose among thorns” is a bit ironic because roses don’t grow among thorns – they have thorns. And South Korea certainly does have a few thorns. Emerging markets in general are out of favor. The political situation has been (and continues to be) tenuous; the country has an aging population and the lowest birthrate in the world. Corporate governance in many of the chaebols is weak, and companies have yet to put into place more minority-shareholder friendly policies (although some are beginning to do so). The Value Up program may or may not prove to bear fruit. In the meantime, the market has been flat for years.

However, as we have described above and elsewhere, there are many roses growing among the thorns. At Kopernik, we are less focused on binary views of “good” and “bad” and keenly focused on where the opinion of the crowd diverges widely from likely reality. It was good to buy Brazil when Lula was elected the first time. The U.S. was best bought during the Watergate Scandal. Buying pharma during the drop resulting from Obama’s first election worked well. The market briefly plunged on the first Trump election. Portugal, Italy, Greece, and Spain proved opportunistic buys when they were derisively called the “PIGS” a decade ago. Those were all uncertain times, but fear was overdone. A dozen years ago, Japan was portrayed as doing all the things that Korea is perceived to be doing now. They’ve made changes, and their market is up fivefold.

At Kopernik, we want to buy good companies at deep value prices, which means that our research analysts do a lot of digging around in the garden looking for opportunities. South Korea presents fertile soil that, in our opinion, investors can ill afford to ignore.

As always, thank you for your continued support.

Mary Bracy

Managing Editor—Investment Communications

January 2025

Important Information and Disclosures

The information presented herein is proprietary to Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is not to be reproduced in whole or in part or used for any purpose except as authorized by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell any product or service to which this information may relate.

This letter may contain forward-looking statements. Use of words such as “believe,” “intend,” “expect,” anticipate,” “project,” “estimate,” “predict,” “is confident,” “has confidence,” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are not historical facts and are based on current observations, beliefs, assumptions, expectations, estimates, and projections. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to risks, uncertainties and other factors, some of which are beyond our control and are difficult to predict. As a result, actual results could differ materially from those expressed, implied or forecasted in the forward-looking statements.

Please consider all risks carefully before investing. Investment strategies discussed are subject to certain risks such as market, investment style, interest rate, deflation, and illiquidity risk. Investments in small and mid-capitalization companies also involve greater risk and portfolio price volatility than investments in larger capitalization stocks. Investing in non-U.S. markets, including emerging and frontier markets, involves certain additional risks, including potential currency fluctuations and controls, restrictions on foreign investments, less governmental supervision and regulation, less liquidity, less disclosure, and the potential for market volatility, expropriation, confiscatory taxation, and social, economic and political instability. Investments in energy and natural resources companies are especially affected by developments in the commodities markets, the supply of and demand for specific resources, raw materials, products and services, the price of oil and gas, exploration and production spending, government regulation, economic conditions, international political developments, energy conservation efforts and the success of exploration projects.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. There can be no assurance that a strategy will achieve its stated objectives. Equity funds are subject generally to market, market sector, market liquidity, issuer, and investment style risks, among other factors, to varying degrees, all of which are more fully described in the fund’s prospectus. Investments in foreign securities may underperform and may be more volatile than comparable U.S. securities because of the risks involving foreign economies and markets, foreign political systems, foreign regulatory standards, foreign currencies and taxes. Investments in foreign and emerging markets present additional risks, such as increased volatility and lower trading volume.

The holdings and topics discussed in this piece should not be considered recommendations to purchase or sell a particular security. It should not be assumed that securities bought or sold in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of the securities in a Kopernik portfolio. Kopernik and its clients as well as its related persons may (but do not necessarily) have financial interests in securities or issuers that are discussed. Current and future portfolio holdings are subject to risk.

- As of 1/6/2025. The information presented is based on the holdings of a fully seasoned representative account that we believe is reflective of the strategy. Holdings and performance of individual accounts will differ based upon, among other things, account restrictions, timing of transactions, and corresponding management fees. ↩︎

- “Overview of official foreign assistance: 1950-60,” K|Developedia ↩︎

- “Election-Related Protests Surged in 2024,” Carnegie Endowment. ↩︎

- As of 1/6/2025. The information presented is based on the holdings of a fully seasoned representative account that we believe is reflective of the strategy. Holdings and performance of individual accounts will differ based upon, among other things, account restrictions, timing of transactions, and corresponding management fees. ↩︎

- “Samsung Set to Account for Half of South Korea’s Economic Growth,” Bloomberg. ↩︎