Conglomerates (Feb 2025)

“A conglomerate is a corporation of several different, sometimes unrelated, businesses. In a conglomerate, one company owns a controlling stake in several smaller companies, conducting business separately and independently.”

-Investopedia

Before delving into the current, sorry state of esteem for conglomerates, it is useful to look back at their storied history from yesteryear. Per The Saturday Evening Post, “Fifty-six years ago, you could hardly rent a car, buy a tennis racket, crank up your stereo speakers, or stock up on cans of corned beef hash without putting money into the pockets of James Ling. As the head of Ling-Temco-Vought (LTV), the Dallas businessman ran more than 11 corporate subsidiaries that made consumer electronics, packaged meat, and even developed aircraft used in the Vietnam War.

Ling’s conglomerate came into being alongside others, like ITT Corp. and Litton Industries, in the booming years of the 1960s. The low interest rates and simplified stock valuation of that era allowed these giants to take unprecedented hold of diverse industries, and in 1968 this magazine pronounced ‘It Is Theoretically Possible for the Entire United States to Become One Vast Conglomerate Presided Over by Mr. James L. Ling.’”

For more of the fascinating story of James Ling, you can read the aforementioned article, dated November 1, 2018. But he was only one of a handful of interesting characters running highly revered conglomerates during the go-go years of the late 1960s. Companies like ITT Corp., Litton Industries, Gulf & Western, Textron, Teledyne, and United Brands were still household names when I came into the business a decade and a half later. Returning to the Saturday Evening Post article, “The business philosophy (of Ling and most of the others) was based on the idea of synergy — or, in the ’60s, synergism — the concept that a conglomerate, as a whole, could be worth more than the sum of its parts…. Cornell University business historian Louis Hyman says, “It’s the first time that management is valorized as completely independent of the thing being managed. That’s how they justified these kinds of unrelated purchases.” The popularization of the MBA and the veneration of managerial science mystified the clever finances being wrought by conglomerate heads like Ling, who used debt and inflated stock valuation to grow their empires.” (We’ll leave it up to the reader whether or not to divine any similarities between the current PE funds and the conglomerates of the ‘60s.)

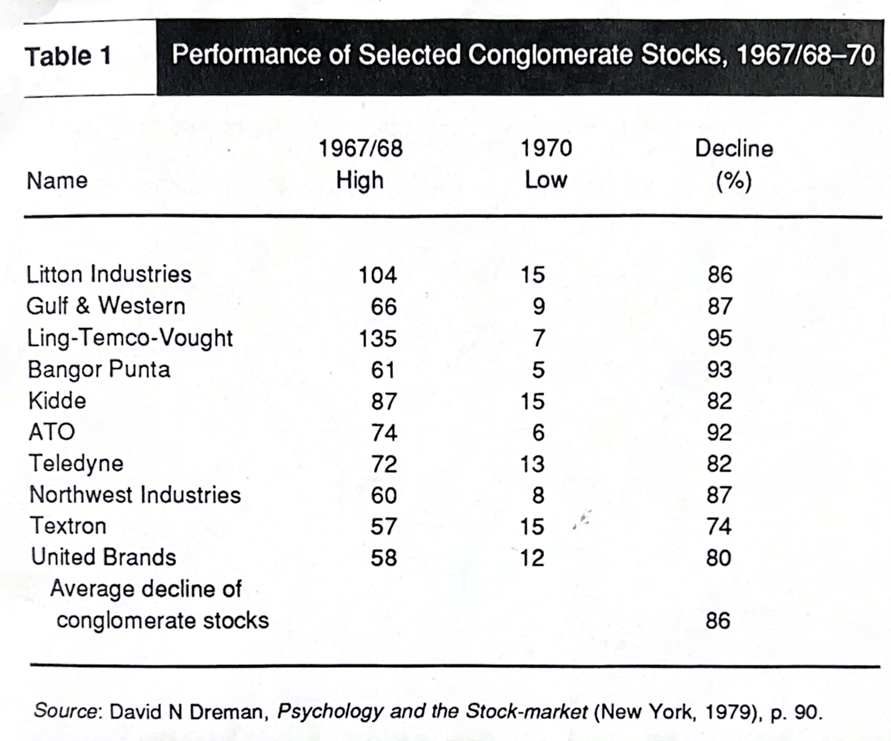

Wall Street loved these stocks for their fast growth, dominance, diversification, and managements who seemingly had the Midas touch. What wasn’t to like? The stocks were massive winners. But alas, like most things that run away with Wall Street’s collective imagination, it ultimately ended in ruin. The adjacent chart from David Dreman (reproduced by Marc Faber in his book The Great Monetary Illusion) highlights the extent of the damage. We recommend the book for those who want to learn more about the go-go markets, amongst other pertinent examples of market inefficiencies.

Like all bear markets, the recklessness with which business had been conducted came well into focus with hindsight. Hence Warren Buffett’s famous quote, “when the tide rolls out, we see who has been swimming naked.” And not surprisingly, conglomerate stocks fell into disrepute. More surprisingly, 55 years later, they remain in the doghouse. Sure, there have been bright spots: in the 1980s it became popular to profitably dismember the conglomerates that had previously been so artfully crafted together; General Electric (GE) became so respected as a conglomerate that it achieved, what at the time was, the largest market capitalization in history, before falling into disrepute itself; and Tyco International was all the rage at the turn of the century before its embezzlement scandal made headlines. On the brighter side, Berkshire Hathaway remains immensely successful and well-respected six decades after Warren Buffett gained control.

The question before us:

“Are Conglomerates Good or are they Bad?”

Our answer is yes to both – they can be good, bad, and everything in between. This is because they are not really a “category” or a “thing,” they are a portfolio of business holdings. In that sense, they are akin to investment funds. Rather than asking “do I like conglomerates,” one should ask, “Do I like these underlying businesses? Do I like this management team? Do I like these valuations?”

We posit that investors who are willing to ponder these questions stand to make excellent investment returns by taking advantage of the current, inordinately large degree of inefficiency in the market. Kopernik Global Investors, consistently taking exception to the Efficient Market Hypothesis, finds that most investors are not rational, but rather are emotional (especially within a crowd) and sometimes are lazy, as well. Regarding the latter, researching conglomerates requires strenuous effort. It entails deep fundamental analysis of multiple companies – often in many different industries, countries, and currencies. The next steps require summing the parts, adjusting for minority interest and the nuances of consolidation accounting, and then risk adjusting for all of the above and more. Frankly, this degree of rigor isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. This gives a competitive edge to those who are willing and able to make the effort.

When it comes to the emotions of crowds, though it is likely self-evident, some examples may be in order. Mentioned previously, conglomerates went from adored in the late 1960s to detritus in the early 1980s. The crowds were wrong at both extremes. A tad more recently, during the first two decades of my career, GE stock went from $5.50 to $280, when over the summer of 2000 it became the largest market cap in the world. Over the ensuing two decades it fell back to $30. This recent summer saw it exceed $200 once again. From 1981 to 1999, the price of the stock far outran the underlying fundamentals. The price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio rose from 7x to 38x; enterprise value-to-sales (EV/S) from 0.48x to 5.6x, and the price-to-book value (P/BV) from 1.4x to 12x. Investors would have been better served to focus on the fundamentals of GE’s portfolio of businesses. For what it is worth, the stock’s P/E and P/BV now exceed the manic high of the previous cycle: 39x and 9.5x, respectively. Caveat Emptor! For more on the topic of cycles and crowd psychology, please read Extraordinary Popular Delusion & the Madness of Crowds (Charles Mackay), Devil Take the Hindmost (Edward Chancellor), Thinking Fast & Slow (Daniel Kahneman), The Undoing Project (Michael Lewis), and/or the Little Book of Behavioral Investing (James Montier).

Interestingly, investment thought isn’t applied consistently. While many conglomerates are still on the outs with investors, trading at steep discounts to their book value, Berkshire Hathaway trades at a nice premium (we have no issue with that premium). Elsewhere, investors seem to have no problem paying full value for collections of businesses if, instead of being held by a conglomerate, they are held by a stock fund (mutual fund, ETF, hedge fund). This applies to REITs and bond funds, as well. If the portfolio of businesses is held by a private equity fund, investors seem happy to pay more than full value, plus pay high management fees and hefty performance fees, and do so while accepting iffy marks (managers estimates of fair price) and risky levels of debt. Similar observations can be made for private credit, venture capital, and hedge funds. Why comparable businesses are accorded very different valuations simply based upon the “wrapper” in which they are held is a mystery to us. Taking advantage of such inefficiencies is our raison d’etre.

When others care more about a portfolio’s ‘wrapper’ than about the quality of its underlying businesses, management, and valuations, opportunities can’t be far behind. While others pay up for PE funds, VC funds, Berkshire and GE, while simultaneously relegating most publicly traded conglomerates to the bargain bin, we are happily accumulating the solid business that they are shunning.

It is helpful and important to remember that it is not a binary world where things are all good or bad. The conglomerate structure has been used to obfuscate numbers and mislead investors. Yet, many conglomerates are well managed. Investors in the 1960s were not wrong about the benefits of “synergism” (synergies). Managements have the ability to add or subtract value over time. As GE was able to do in the early days, a good management team can use the cash flow from a thriving business to help grow or protect other emerging (or struggling) businesses within the portfolio. These are some of the reasons that investors like the conglomerate approach when it is referred to as private equity, VC, etc., as mentioned earlier. There are significant advantages. Why publicly traded equity portfolios are singled out for disdain is anybody’s guess and everybody’s opportunity.

Kopernik’s Approach to Conglomerates

In our search for attractive conglomerates, we use a “sum-of-the-parts” approach – analyzing each meaningful component of the conglomerate individually. We appraise each one on its own merit, sum them together and make necessary adjustments. We then factor into the analysis our opinions of management’s ability to add or subtract value over time. We prefer to focus on conglomerates that have businesses with good fundamentals, and which have a long track record of growing tangible book value. We gravitate towards those with substantial insider ownership and strongly prefer the parts of the conglomerate where we are most aligned with management. Today, we are finding many opportunities in Asia, especially in South Korea and China. These companies are significantly undervalued, similar to where the Japanese trading companies were a half dozen years ago.

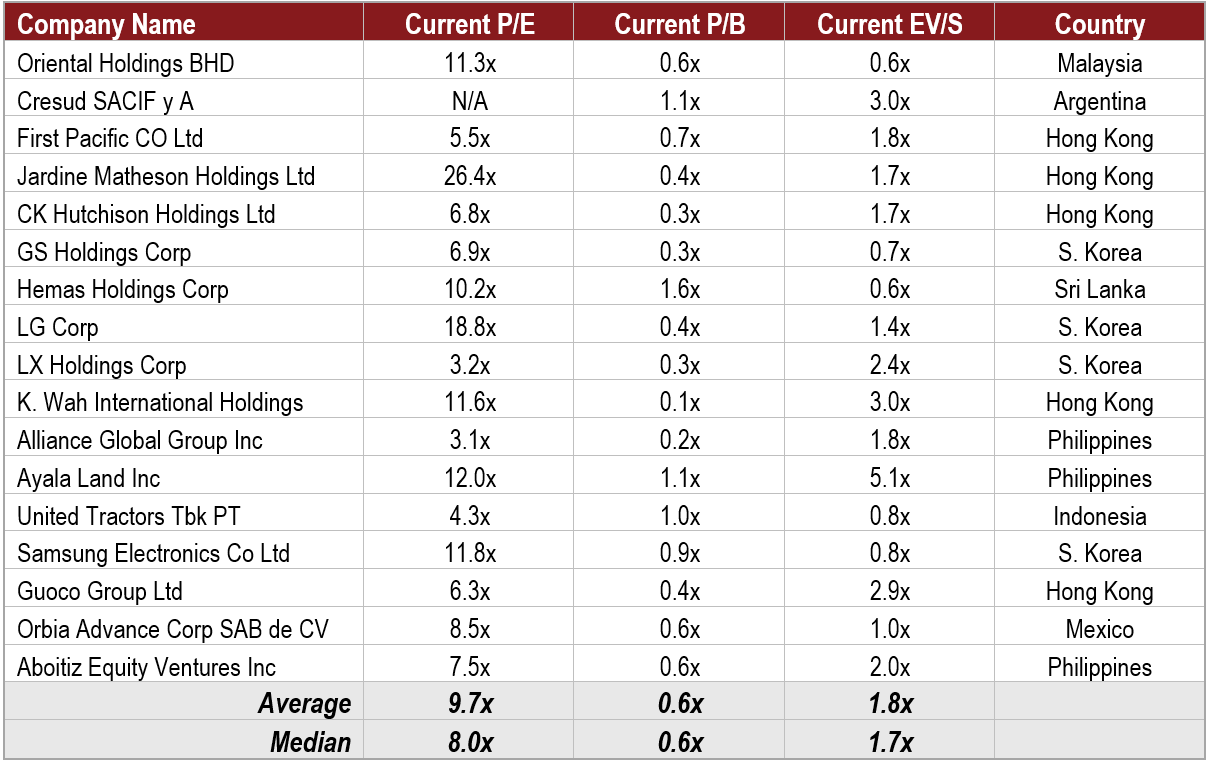

As was the case for a younger United States in the days of Vanderbilt, Morgan, Carnegie, and Rockefeller, emerging markets tend to have a lot of power concentrated in a few hands, usually in a conglomerate structure. We like holding some of the best assets in many promising emerging countries. See the table below for a hint at the type of value available in the conglomerate universe. Most are consistently profitable, pay nice dividends (without borrowing to do so), and grow book value as well.

As of 2/13/2025. Kopernik has positions in Oriental Holdings BHD, Cresud SACIF y A, First Pacific Co Ltd, Ck Hutchison Holdings Ltd, GS Holdings Corp, Hemas Holdings Corp, LX Corp, LG Holdings, K. Wah International Holdings, United Tractors TBK PT, and Samsung Electronics Co Ltd.

Lest we assume these valuations speak for themselves, consider that the P/E of the S&P 500 Index is currently 25.7x. Please see the Appendix for further discussion of how the market’s P/E is in reality much more daunting than it appears.

Below are some of the low-priced conglomerates that have been creating value, even as the stock price sags:

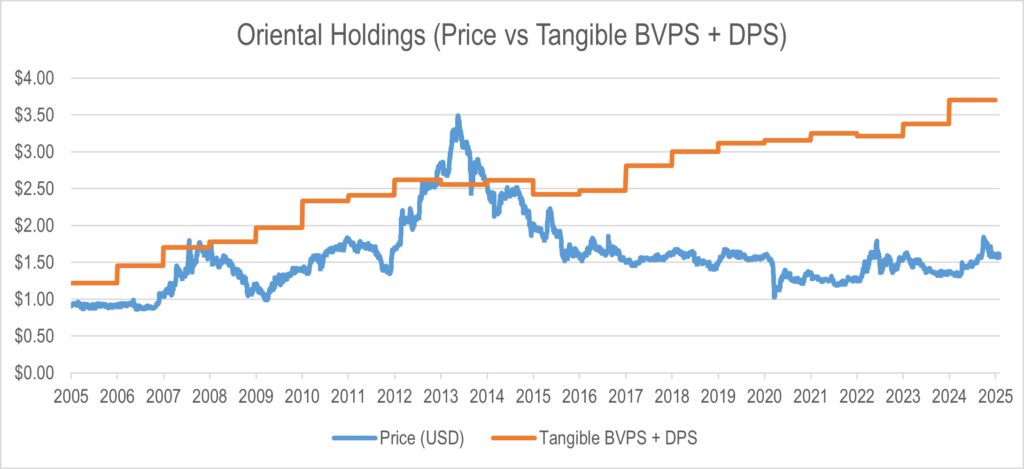

Oriental Holdings BHD (“Oriental Holdings”) is a Malaysia-based holding company. They have palm oil plantations and an automotive distribution business, own hotels and resorts, and manufacture plastic products. They also own investment properties and operate a nursing college and hospital. The company has low balance sheet leverage and has grown tangible book value per share (TBVPS) 2.5x over two decades—while paying a 5% dividend.

As of 2/13/2025, Kopernik has a position in Oriental Holdings.

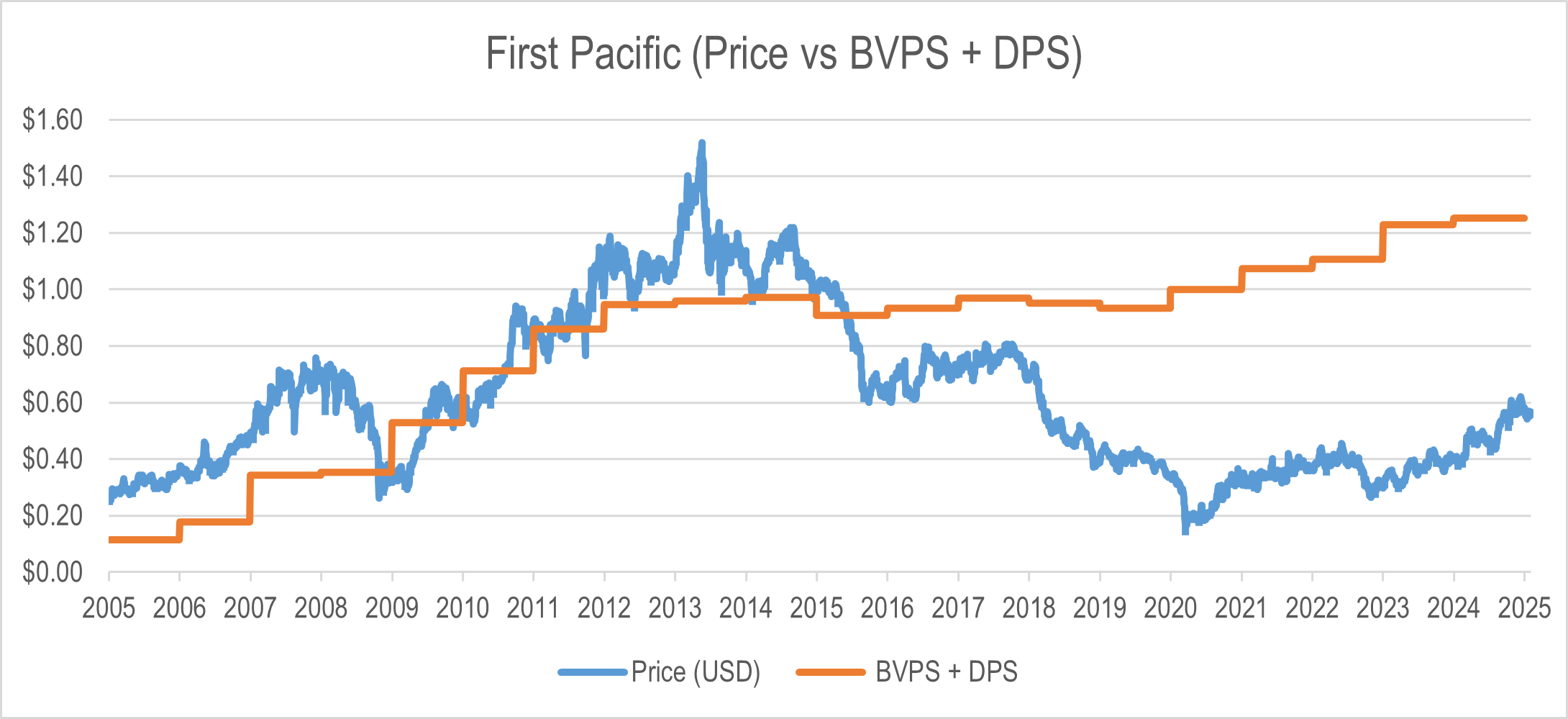

First Pacific Co Ltd (“First Pacific”) is a Hong Kong-based company operating in the Philippines and Indonesia, where it is the dominant player in consumer staples. They also have businesses in copper/gold mining, telecom, palm oil plantations, and infrastructure. The company has grown book value per share (BVPS) by 9x over two decades, while paying a 5% dividend.

As of 2/13/2025, Kopernik has a position in First Pacific

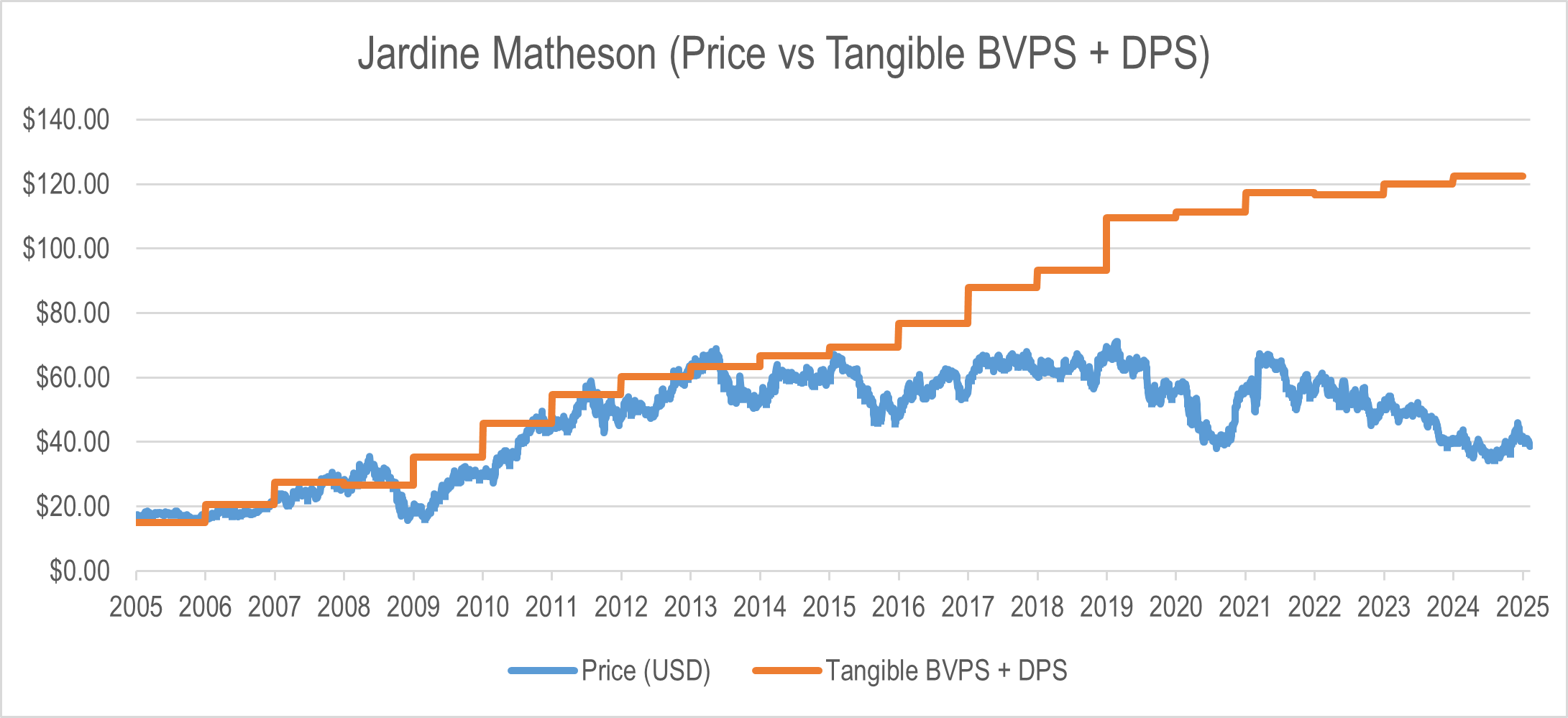

Jardine Matheson Holdings Ltd (“Jardine Matheson”), founded in China in 1832 by two Scotsmen, William Jardine and James Matheson, is today a Hong Kong-based company that operates in more than 30 countries. Their business segments include automobiles, financial services, hotels, construction, mining, and transportation services. The company has grown TBVPS 8x over two decades, while paying a 5% dividend.

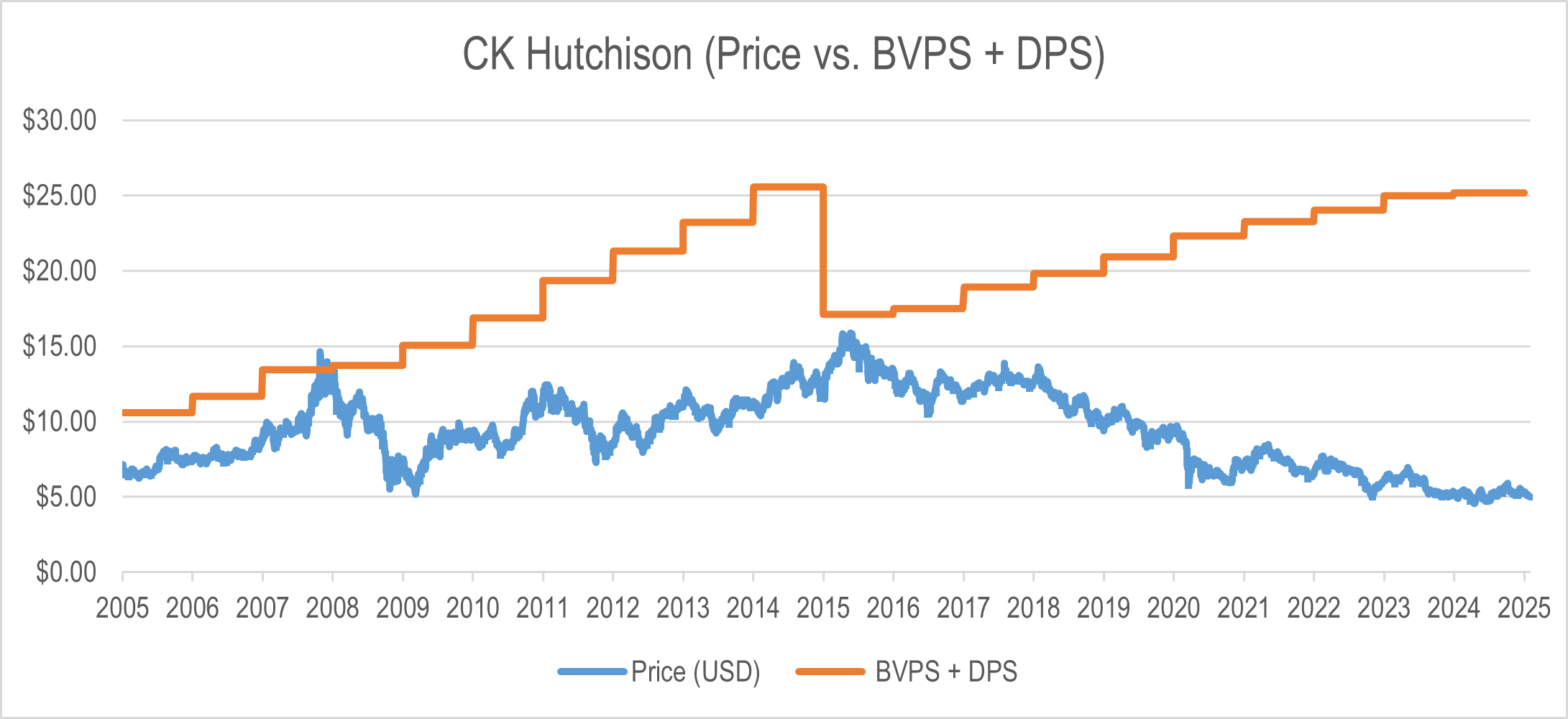

Hong Kong-based CK Hutchison Holdings Ltd (“CK Hutchison”) holds interests in 53 ports in 24 countries, is the world’s largest international health and beauty retailer, and one of the largest wireless telecom providers in Europe. It also has business segments in infrastructure and financial services. The company has grown BVPS over 90%, while paying a 6% dividend.

As of 2/13/2025, Kopernik has a position in CK Hutchison.

CK Hutchison underwent a corporate restructuring in 2015 that spun off their property business, causing the large drop in BVPS.

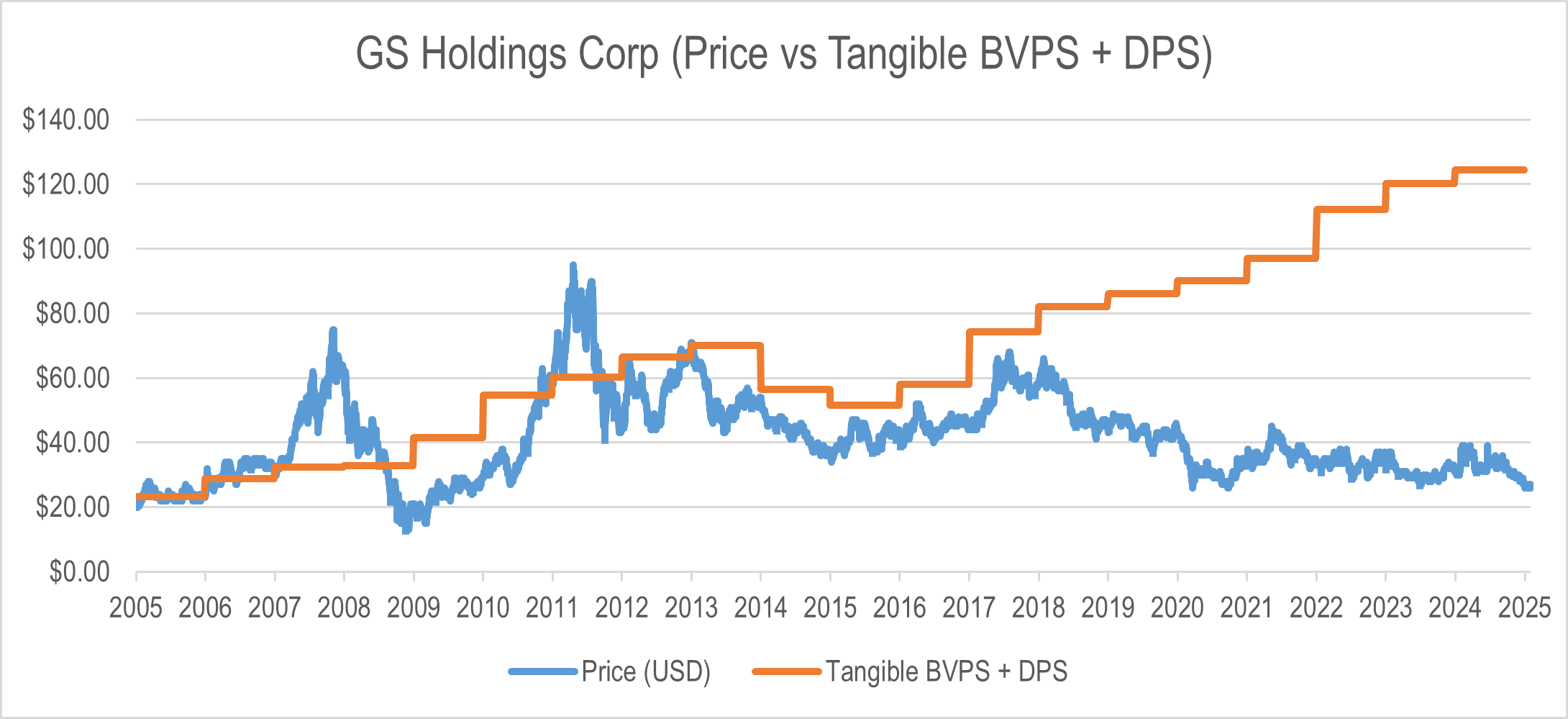

GS Holdings Corp is a South Korea based investment-holding company spun off from LG Corp in 2005. It has an oil refining and marketing business, operates 13 power plants in Korea, and operates convenience stores and supermarkets. The company has grown TBVPS by 4.5x, while paying a 5% dividend.

As of 2/13/2025, Kopernik has a position in GS Holdings Corp.

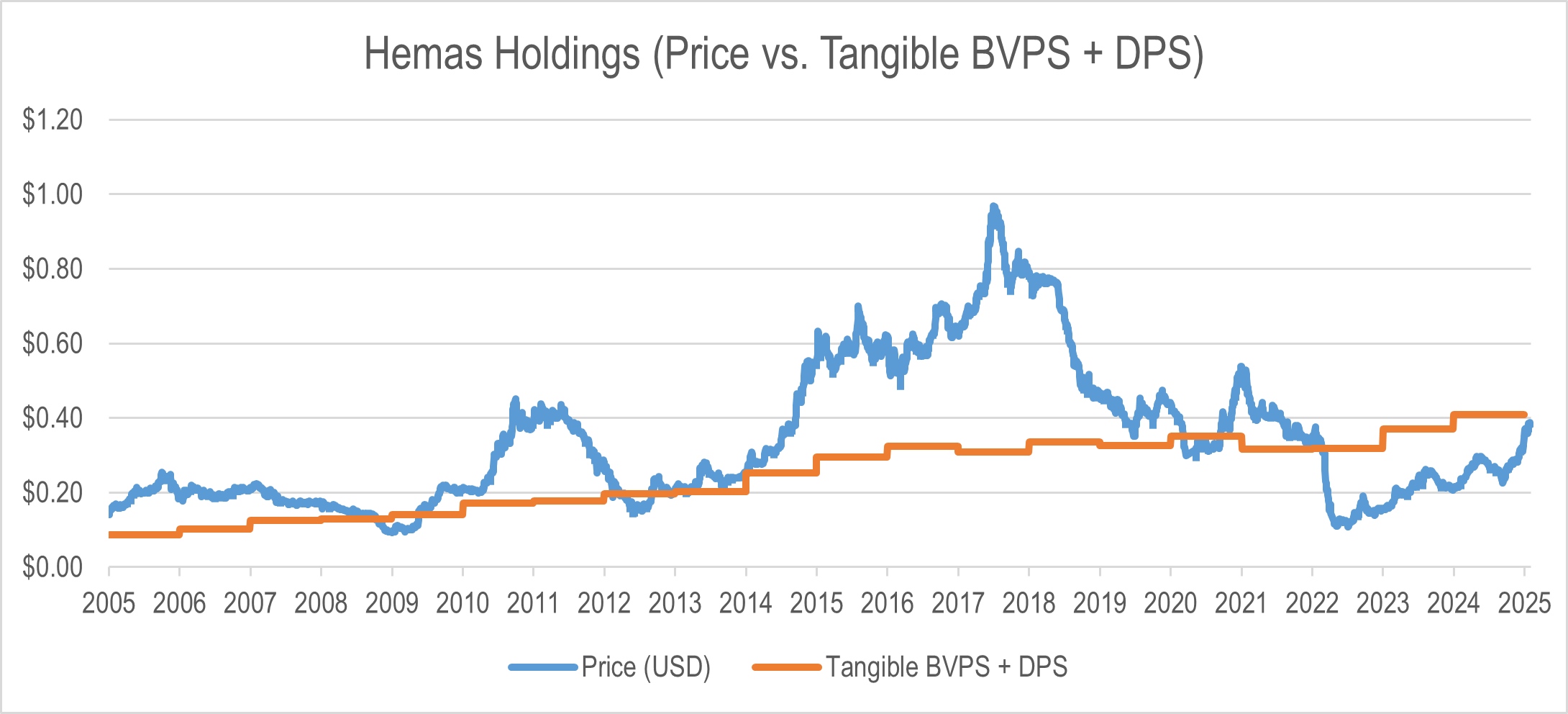

Hemas Holdings is a Sri Lankan conglomerate. They are the country’s largest private healthcare service provider, pharmaceutical manufacturer and distributor, and domestic personal care company. They also have shipping and distribution operations. The company has quintupled its TBVPS while still paying dividends.

As of 2/13/2025, Kopernik has a position in Hemas Holdings.

This is but a small sample—there are many others. Additionally, if one fancies real estate or financials, the list of bargains is quite large. We continue to actively do due diligence on many conglomerates.

Conclusion

Conglomerates are portfolios of businesses which should be evaluated on their own individual merits. Recent investor proclivity to lump them all together and affix a negative connotation has created an exciting investment opportunity for those who are willing to do the requisite fundamental analysis.

As always, thank you for your continued support.

David B. Iben, CFA

Chief Investment Officer

Portfolio Manager

February 2025

Appendix

P/E ratios across the large indices are high—the S&P 500 has a P/E of 25.7x, as mentioned above; the NASDAQ’s P/E is 38.0x, and the Russell 2000 has a P/E of 33.5x. Investors who assume that passive index funds are being honest about the numbers, however, may be off base, as David Collum points out in his 2024 Year in Review:

Let’s take, for example, the QQQ tech index or the Russell 2000. But wait a darn tootin’ minute, pardner. Both indices have P/E’s that are listed around 30. Well, since you brought that up, in 2017 Horizon Kinetics dug into the QQQ and discovered as described in their prospectus that they fudge the numbers. The P/E ratios are averaged. Here is where it gets funky. All stocks with a P/E above 40 are rounded by the ETF protocols to 40, and all stocks with no (or negative) earnings are assigned a P/E of 40. This is tantamount to putting a theoretical P/E cap at 40. Horizon Kinetics, by contrast treated the QQQ ETF as a gigantic Berkshire-like tech entity and simply added up the market caps and divided by the net earnings (earnings minus losses) to get a P/E of 90. I’m bettin’ it’s 100 by now (pardner). That same year Mark Hulbert did the same exercise with the Russell 2000 and also got a P/E of 90. You think you are buying a 3% annual cash flow with potential for rapid growth while, in reality, you are buying a 1% cash flow. But, hey Boo, the potential for earnings to double over and over again is still there.

Important Information and Disclosures

The information presented herein is proprietary to Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is not to be reproduced in whole or in part or used for any purpose except as authorized by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell any product or service to which this information may relate.

This letter may contain forward-looking statements. Use of words such as “believe,” “intend,” “expect,” anticipate,” “project,” “estimate,” “predict,” “is confident,” “has confidence,” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are not historical facts and are based on current observations, beliefs, assumptions, expectations, estimates, and projections. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to risks, uncertainties and other factors, some of which are beyond our control and are difficult to predict. As a result, actual results could differ materially from those expressed, implied or forecasted in the forward-looking statements.

Please consider all risks carefully before investing. Investment strategies discussed are subject to certain risks such as market, investment style, interest rate, deflation, and illiquidity risk. Investments in small and mid-capitalization companies also involve greater risk and portfolio price volatility than investments in larger capitalization stocks. Investing in non-U.S. markets, including emerging and frontier markets, involves certain additional risks, including potential currency fluctuations and controls, restrictions on foreign investments, less governmental supervision and regulation, less liquidity, less disclosure, and the potential for market volatility, expropriation, confiscatory taxation, and social, economic and political instability. Investments in energy and natural resources companies are especially affected by developments in the commodities markets, the supply of and demand for specific resources, raw materials, products and services, the price of oil and gas, exploration and production spending, government regulation, economic conditions, international political developments, energy conservation efforts and the success of exploration projects.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. There can be no assurance that a strategy will achieve its stated objectives. Equity funds are subject generally to market, market sector, market liquidity, issuer, and investment style risks, among other factors, to varying degrees, all of which are more fully described in the fund’s prospectus. Investments in foreign securities may underperform and may be more volatile than comparable U.S. securities because of the risks involving foreign economies and markets, foreign political systems, foreign regulatory standards, foreign currencies and taxes. Investments in foreign and emerging markets present additional risks, such as increased volatility and lower trading volume.

The holdings and topics discussed in this piece should not be considered recommendations to purchase or sell a particular security. It should not be assumed that securities bought or sold in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of the securities in a Kopernik portfolio. Kopernik and its clients as well as its related persons may (but do not necessarily) have financial interests in securities or issuers that are discussed. Current and future portfolio holdings are subject to risk.