Jacoby Transfers (Jul 2023)

Bridge is a fascinating card game. It combines strategy and memory, bidding the hand with playing the hand. Part of the allure is that it requires a complex system of communication where a bid can have differing meanings depending upon agreed upon conventions. For example, a bid of 2 clubs would signify something to one’s partner. Whereas in another partnership, 2 clubs could signify a completely different message. One very commonly used convention is the Jacoby transfer, or simply transfers. It forces the opener to rebid the next higher ranked suit. Transfers were popularized for English speakers in 1956 in The Bridge World article by Oswald Jacoby.

It seemed like a nice title, despite the seemingly divergent facts that we will be discussing: investing, not bridge playing; Carl Jacobi instead of Oswald Jacoby; and improving one’s vantage point when analyzing an investment or using a valuation model, rather than transferring card suits.

Before moving on, I will say that bridge, like poker, is a wonderful game that combines a high level of strategy and skill with the luck of the cards. As such, they are both similar, in many ways, to investing. I’m a big fan of all three. Chess eliminates the chance factor but is still akin to investing, as testified below:

“Magnus Carlsen came by to discuss similarities between chess and investments.

Decisions under stress, calculated moves and pattern recognition.

Bounce back after losses, stay cool and NEVER give up!”

-Nicolai Tangen, CEO of Norges Bank Investment Management, the world’s largest sovereign wealth fund.

Mr. Carlsen is a Norwegian chess grandmaster who is a former 5-time World Chess Champion (2013–2023) and current 4-time World Rapid Chess Champ and 6-time World Blitz Chess Champ.

“Life, in part, is like a poker game,

wherein you have to learn to quit sometimes when holding a much-loved hand,

you must learn to handle mistakes and new facts that change the odds.”

-Charlie Munger

Improving One’s Vantage Point

“Men will always be mad, and those who think they can cure them are the maddest of all.” - Voltaire

“In individuals, insanity is rare, but in groups, parties, nations, and epochs, it is the rule.” - Friedrich Nietzsche

“The scientists of today think deeply instead of clearly. One must be sane to think clearly, but one can think deeply and be quite insane.” -Nikola Tesla

“People calculate too much and think too little.” -Charlie Munger

It is hard not to be impressed with the wisdom of Charlie Munger. He is, of course, a proponent of mental lattices and viewing things from different perspectives. He likes the saying “invert, always invert.”

Munger has adopted the concept of inverting a problem to find solutions. Inspired by the mathematician Carl Jacobi, he said:

Invert, always invert:

Turn a situation or problem upside down. Look at it backward.

What happens if all our plans go wrong? Where don’t we want to go, and how do you get there?

Instead of looking for success, make a list of how to fail instead –

through sloth, envy, resentment, self-pity, entitlement, all the mental habits of self-defeat.

Avoid these qualities and you will succeed.

Tell me where I’m going to die, that is, so I don’t go there.

– Charlie Munger

This concept can be applied to investing – think: “what could go wrong in this investment?” As Buffett and Munger found out, success in investing is more about avoiding losers, than finding winners.

This sets up many of the points we hope to make in this paper. But first, if you’re like me, you may already be looking up Carl Jacobi. Here is a very abridged synopsis (per Wikipedia):

Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi

(/dʒəˈkoʊbi/;[2] German: [jaˈkoːbi]; 10 December 1804 – 18 February 1851)

Was a German mathematician who made fundamental contributions to elliptic functions, dynamics, differential equations, determinants, and number theory.

His many contributions are too numerous to add here, but this article from jamesclear.com adds the following:

“The German mathematician Carl Jacobi made a number of important contributions to different scientific fields during his career. In particular, he was known for his ability to solve hard problems by following a strategy of man muss immer umkehren or, loosely translated, “invert, always invert.”

Jacobi believed that one of the best ways to clarify your thinking was to restate math problems in inverse form. He would write down the opposite of the problem he was trying to solve and found that the solution often came to him more easily.

Inversion is a powerful thinking tool because it puts a spotlight on errors and roadblocks that are not obvious at first glance. What if the opposite was true? What if I focused on a different side of this situation? Instead of asking how to do something, ask how to not do it.”

This approach aligns Jacobi with some of the greatest minds of the ancient world: the stoic philosophers Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, and Epictetus. Munger has said that he relates to stoic philosophy. Certainly, many of his quotes have strong stoic underpinnings. James Clear continues with:

“The Stoics believed that by imagining the worst-case scenario ahead of time, they could overcome their fears of negative experiences and make better plans to prevent them. While most people were focused on how they could achieve success, the Stoics also considered how they would manage failure. What would things look like if everything went wrong tomorrow? And what does this tell us about how we should prepare today? This way of thinking, in which you consider the opposite of what you want, is known as inversion.”

As we delve deeper into philosophy, a disclaimer is in order – way back in school, I was always a math/science geek with little use for the social sciences or humanities, so I’m way out of my circle of competence here. However, I do find the juxtaposition between stoicism on one hand, and the thoughts of Friedrich Nietzsche, on the other hand, to be fascinating. The devotees of reflexivity, in particular, seem to be the modern-day antithesis of stoic thought.

“The theory of reflexivity is defined as follows – human behavior is determined not by reality, but by subjective perceptions of it.

It is a kind of ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ when subjects treat a situation as real, then this situation becomes real in its consequences.”

On the stoic side is the belief that one cannot have much impact on the world, and therefore should focus on controlling oneself. On the side of reflexivity is the belief that one can, and should, have an impact on the outside world. One’s actions can forever change the world, and reality is ever subjective and not rational. Stoics place virtue above all else while some reflexivity cohorts seemingly put winning above all else, often rationalizing the ethical considerations.

(As an aside, sadly, Milan Kundera passed away the other day. An excellent author, he was a fan of Nietzsche and wrote a lot about the methods and effects of the Soviet infiltration of his native Czechoslovakia. It’s not hard to see parallels between those methods and those being employed by today’s movers and shakers.)

The stoics imagine what could go wrong, hoping to prevent or rectify. Modern philosophies teach that optimism is self-fulfilling, and individuals and groups can actualize positive outcomes.

Who’s correct? A quarter-millennium of American history suggests that optimism always pays. Suggests? It shouts it. Aggressive bets pay handsomely. And while money and power have always carried a lot of weight, it is increasingly clear that this era of unlimited money printing has bestowed almost unlimited power on the privileged class, enabling them to use a turbocharged version of reflexivity. The tail has been wagging the dog. With enough firepower, blitz-scaling is a formidable strategy. Political Action Committees (PACs) allow the powerful corporations to enact preferential laws and to otherwise stack the deck in their favor. A notable example was the ability of many large corporations to gain access to loans at de minimis interest rates while smaller competitors were closed due to covid legislation, etc. Even before the real blizzard of currency, if one could count on enough followers, one could “break the Bank of England.” The clout of the powerful is nearing a cyclical high, as Matt Stoler describes well in Goliath: The 100-year War between Monopoly Power and Democracy. In 2023, stoicism seems to be a 3,000-year-old relic. Reflexivity rules the day.

“It’s like the slaughter of the innocents.

It makes the people who run Las Vegas seem like good people.”

– Charlie Munger

While it seems a lopsided contest, few will be surprised that the rest of this commentary will be devoted to the idea that a stoic approach may be beneficial in today’s environment.

In general, this is the Munger approach:

“It is remarkable how much long-term advantage people like us have gotten by trying to be consistently not stupid, instead of trying to be intelligent.”

“The big money is not in the buying and the selling, but in the waiting.”

“People calculate too much and think too little.”

“You must force yourself to consider opposing arguments. Especially when they challenge your best-loved ideas.”

“Acknowledging what you don’t know is the dawning of wisdom.”

“You don’t have to be brilliant, only a little bit wiser than the other guys, on average, for a long time.”

“Assume life will be really tough, and then ask if you can handle it. If the answer is yes, you’ve won.”

“I would argue that passion is more important than brain power.”

“Knowing what you don’t know is more useful than being brilliant.”

“It’s waiting that helps you as an investor and a lot of people just can’t stand to wait. If you didn’t get the deferred-gratification gene,

you’ve got to work very hard to overcome that.”

“All intelligent investing is value investing, acquiring more than you are paying for.”

“Confucius said that real knowledge is knowing the extent of one’s ignorance. Aristotle and Socrates said the same thing. Is it a skill that can be taught or learned? It probably can, if you have enough of a stake riding on the outcome…”

We’re asking a few questions in this commentary. For starters, in our cyclical world, where too much of anything usually sows the seeds of its own destruction, can all these trends go to the sky? Secondly, can every attempt to blitz-scale win? Can more than a few of those companies that are striving for dominance win? Might people begin to support the underdogs? Are the stoic virtues (courage, temperance, wisdom, justice) obsolete?

Our first focus is on the concepts of inverting and imagining what could go wrong.

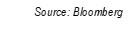

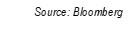

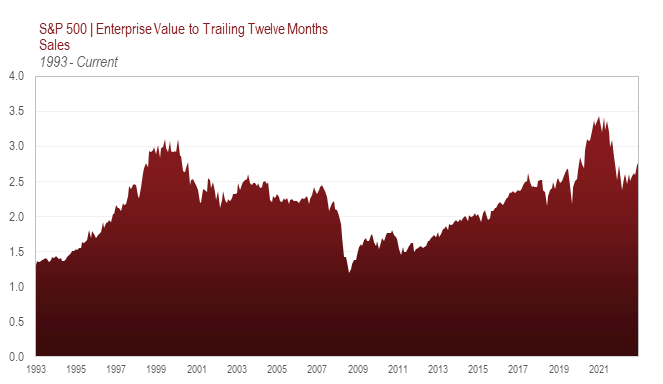

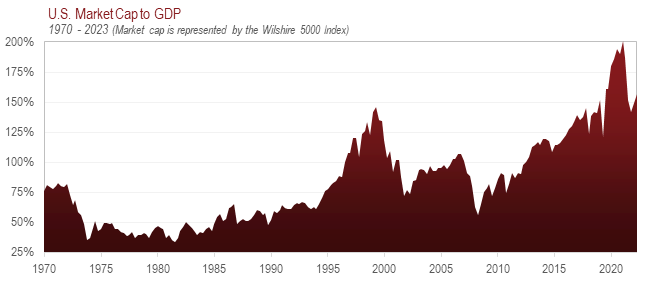

For example, look at the following charts…

Is it difficult to imagine what could go wrong? Do the following valuation-focused charts make it any easier?

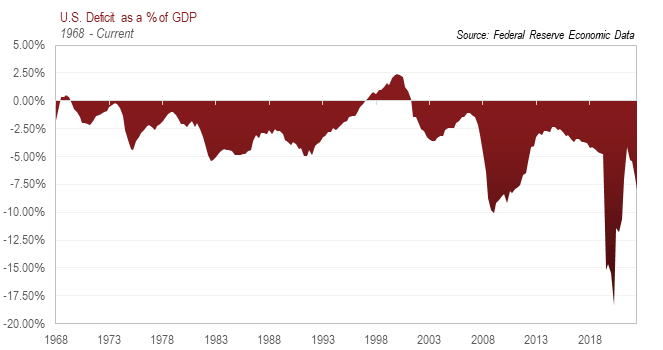

But don’t the fundamentals support higher prices? The economy has grown. True, but it has been outgrowing its economic underpinning, as demonstrated below:

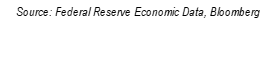

But, if low interest rates support higher valuations, can we envision higher rates in the future?

As of July 2023, a ten-year Treasury Bond (T-Bond) yields nearly 4%, meaning that if held to maturity an investor stands to make nearly 4% per year. Reasonable people can debate whether that is more or less than the rate of inflation. Bonds are no longer the poster child of “return-free risk,” as they were for much of the past decade, but still represent a risk/return proposition to be steadfastly avoided. Granted, if 10-year rates instantly fall back to last year’s lows (also the lows of the written history of mankind) the lucky bondholder would benefit from the healthy 34% appreciation. Unfortunately, a quick return to the levels of 1981 would result in almost a 60% destruction of wealth. Many financial assets would be similarly affected.

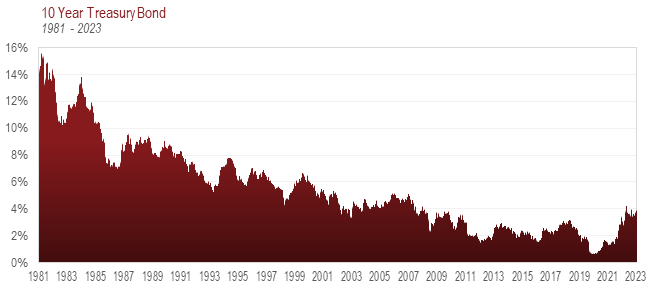

But isn’t inflation “transitory”?

Will this be remedied? Defaulted on? Inflated away? History and logic make a compelling argument that high debt levels and lax fiscal discipline invariably lead to higher inflation, and that inflation migrates through the system in waves. It is seldom “transitory.” Democracies, for all their virtues, famously have a tendency toward lax finances.

“Many forms of Government have been tried and will be tried in this world of sin and woe.

No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the

worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.…’

-Winston S Churchill

“The best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter.”

-Winston S. Churchill

“I do not know if the people of the United States would vote for superior men if they ran for office,

but there can be no doubt that such men do not run.”

-Alexis de Tocqueville

“A democracy cannot exist as a permanent form of government. It can only exist until the voters discover that they can vote themselves largesse from the public treasury.”

-Alexander Fraser Tytler

‘Fiat currency always eventually returns to its intrinsic value–zero.’

-Voltaire

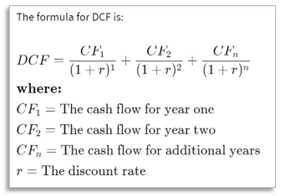

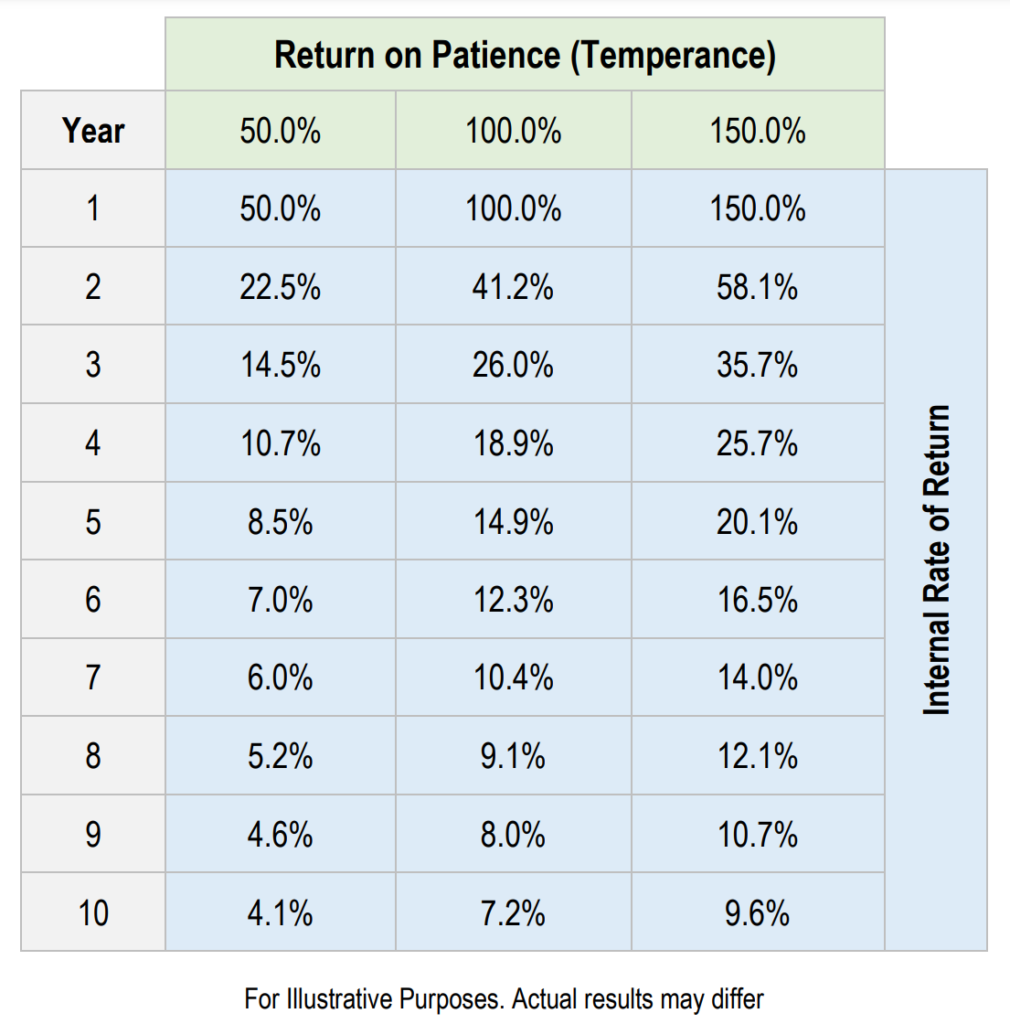

Howard Marks often uses Elroy Dimson’s insightful remark that, “risk means that more things can happen than will happen.” Stoics say that by anticipating some of the worst possibilities, one can define, prevent, or repair adverse outcomes. Kopernik says one should anticipate potential bad outcomes so that one can assign probabilities, establish appropriate margins of safety, invest where large positive asymmetries exist, and diversify away much of the risk. Kopernik agrees with the stoic concept that when performing investment analysis, it is helpful to invert. Let’s touch on four ways that we do this: 1) create templates to normalize margins; 2) focus on areas passed over by indexers, i.e., undercapitalized sectors; 3) use multiple, unconventional valuation metrics; 4) an important subset of #3 – invert the discounted cash flow (DCF) model, solving for acceptable internal rates of return (IRRs).

Taking the Road Less Travelled

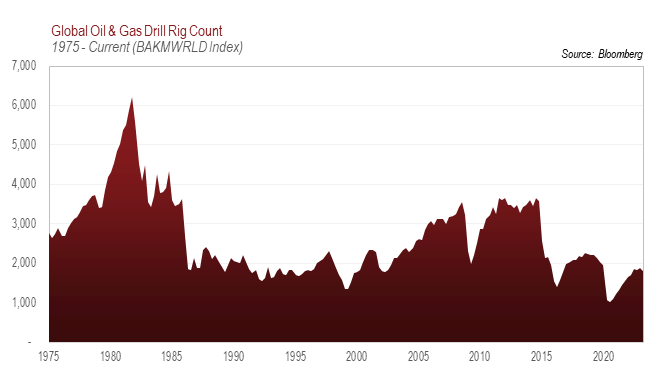

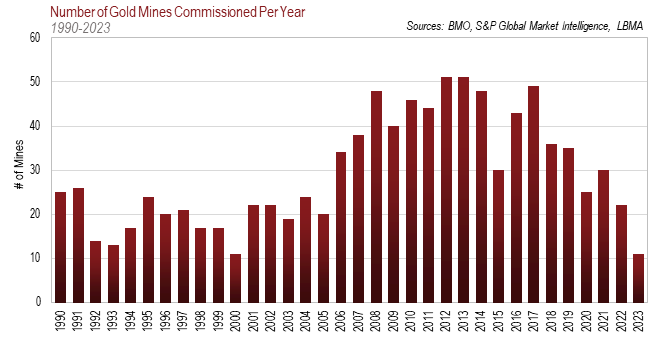

In Introductory Econ, we learn about Supply and Demand. We’ve been taught about the problems associated with too much supply. Yet, investors, as they chase “the hot dot,” don’t realize that they are often sowing the seeds of their own demise. When an industry is doing well, stock prices rise. Many companies take advantage of their valuable stock to raise money, which they often use to invest in more capacity. Clients are usually clamoring for more of their wares at that point in the cycle. This often goes on for years, reaching a frenzy during the final year of a cycle. Sooner or later, supply exceeds demand, prices fall, and stocks plunge. During the ensuing years, the companies find religion, pay down debt, and husband their cash. They don’t even consider investing in capacity, of which there is seemingly too much. Eventually, demand picks up, capacity is insufficient, prices rise, and a new cycle begins.

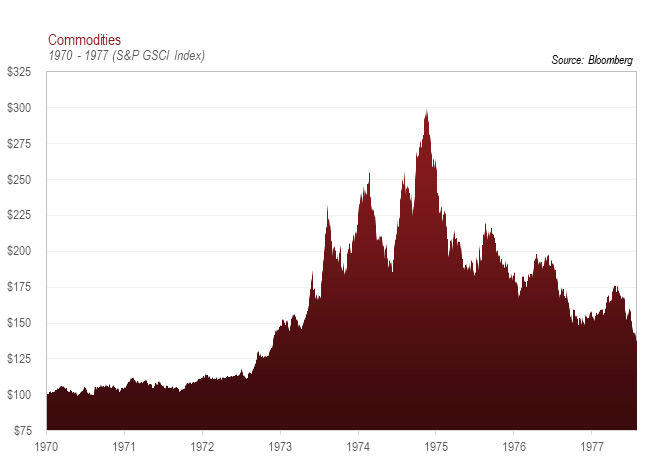

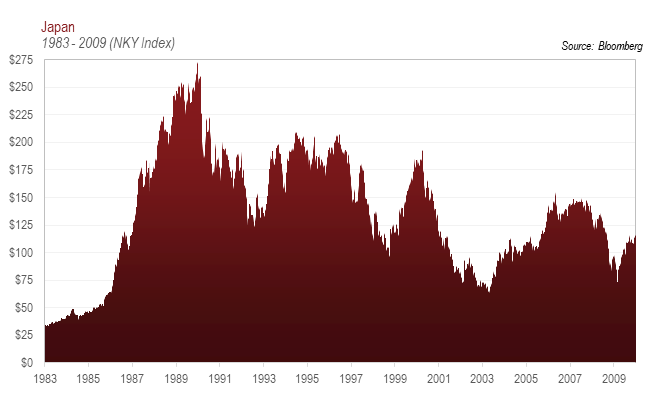

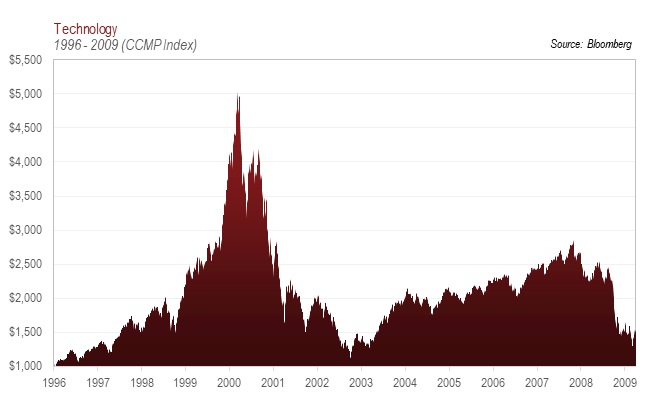

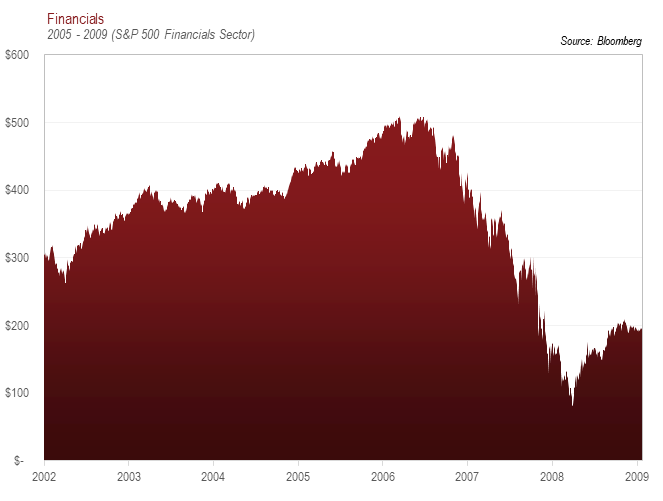

While it is so logical (and apparent with the aid of 20/20 hindsight), common sense gets lost in the heat of the moment. Beaucoup bucks were thrown at natural resources, Japan, technology, and financials during the late 70s, late 80s, late 90s, and the mid-aughts, respectively – with disastrous results. In every case, more than three-quarters of the value was eviscerated during a long, painful bear market. Much later, all of these areas proved to be great investments following years of neglect and underinvestment.

Currently, when looking for opposite ends of the emotional spectrum, the contrast between markets in the U.S. and the rest of the world is shocking. As much as we love the U.S., we suspect that over 60% of the MSCI All Country World Index (ACWI) being in one country will go down in history as a prime example of too much money chasing a good thing. It’s possible that it gets painful. The inverse is attractive – only ten percent of the ACWI being allocated to half the world could prove to be massive underinvestment and a once-in-a-lifetime investment opportunity. Of course, we’re referring to emerging markets (EM), which are oddly considered a market niche despite holding most of the world’s people, land, resources, and potential growth. Emerging markets represent roughly half of the world’s GDP.

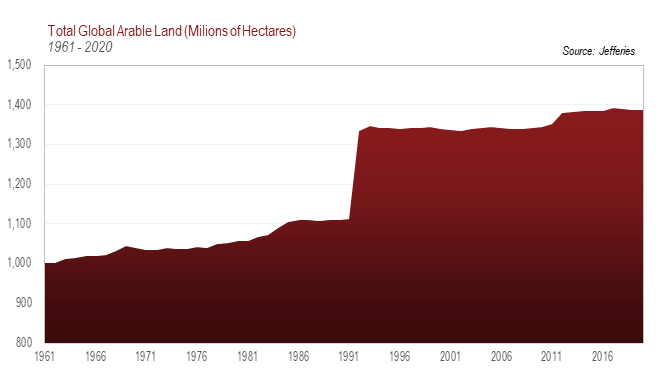

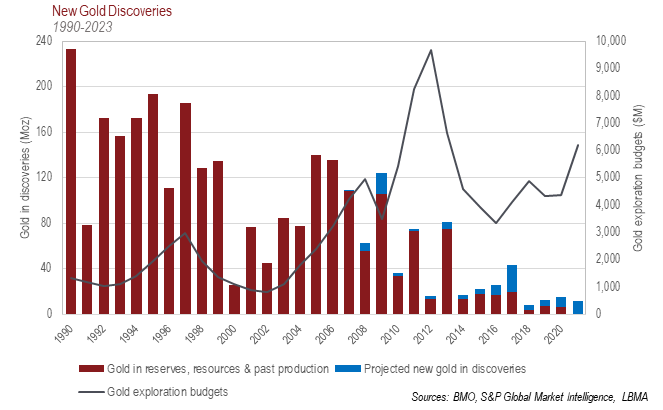

Secondly, as was the case a quarter century ago, companies providing basic human needs such as food production, electricity, energy, metals, and hard money, have endured a long bear market, with concomitant under investment. Meanwhile, the earth’s population is eight billion and growing. The stars are aligned.

To reiterate, too much capital sows the seeds of future overcapacity/recession. Too little investment lays the foundation for future improvement.

“When the whole world is running towards a cliff,

he who is running in the opposite direction appears to have lost his mind.”

– C.S. Lewis

What Appears to Be So Versus What Ought to Be So

Large profit margins are the well-deserved result of superior products and services that meet the needs and wants of the masses. They can also be the result of a short-term phenomenon, an intermediate-term cyclical high, or a longer-term secular peak, none of which are sustainable. They are often the result of clever, but perfectly legal, use of accounting rules. In some, fortunately rare, cases they are the result of outright fraud. Most investors, including ourselves, use the audited financial data as presented. Some, including ourselves, read the very boring but highly informative notes to the financial statements. This is often where the important information is “hidden.”

But, beyond the requisites above, we find it helpful to invert the analytical framework from what is presented to what it logically ought to be. Before looking at the data (to limit the anchoring heuristic), we study the fundamentals of an industry. Are supply and demand factors conducive to high margins or growth? Are there high barriers to entry to prevent high margins from promptly being competed away? Are there barriers to exit that can lead to sustained losses? Does the industry favor those with low costs, size, brand recognition, favorable asset quality, geographic advantages, or smart management, for example? Based on these factors, we will assess a range of reasonable margin assumptions. When the presented data is superior to “reasonable” expectations, we avoid the securities. These are sometimes winners, but often prove to be the dreaded “value trap.”

Marcus Aurelius, another famed stoic, stated something to the effect that where others see Caesar’s luxurious robe, he sees a piece of cloth that has been dyed with shellfish blood. What would he make of Bernard Arnault becoming the wealthiest man in the world essentially by taking consumer goods such as handbags, dressing them up, and selling them for thousands of dollars? Could he have imagined this not being sustainable? Or, several years ago when another man became the richest on earth by getting the government to subsidize his automobiles (via government rebates) and require his competitors to pay him money, would he have imagined things differently? A decade ago, few could have imagined that it would be considered okay that companies whose cars run on hydrocarbons converted into gasoline should be required to make payments to car companies that run primarily off of hydrocarbons that have been converted into electricity. This is an era that requires imagination, that tests credulity. Lululemon is an incredible success story. If it ever comes to be seen as merely an apparel company, 6 times revenues will prove to have been a dangerous valuation. Similarly, hats off to Chipotle for building a great franchise. But few things have lower barriers to entry than Mexican food restaurants. If they ever become perceived that way, 56 times earnings and 24 times book value will be viewed with disbelief by future generations. The market is effectively valuing restaurants at 24 times what it cost to build them. Competition is on the way. We can move on without mentioning the “Magnificent Seven,” the sobriquet for the mega-cap tech stocks that are almost singlehandedly responsible for the market’s gains this year. To envision these stocks selling at less than half of today’s level requires little imagination. One need merely look at their prices from last October.

Companies that are “underearning” their fundamentals and are attractively valued even if the underearning continues are especially interesting to us. Those willing to think differently than the crowd can expect good returns in the status quo while getting a value “free” option to receive outsized returns if/when the company fulfills its potential. For example, society seems to be reevaluating the premium previously placed on processed foods relative to whole foods.

Through the Looking Glass

This phrase first appears in the title of a book written by Lewis Carroll as a sequel to 1865’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. There, it means “opposite to what’s expected by someone;” here, it symbolizes things in an alternative universe, totally opposite to the real world. How apropos to a world that has seen interest rates at equal or less than zero for much of the last decade and a half; a decade that saw the U.S. Federal Reserve increase the supply of “money” by an astounding factor of ten! For thousands of years (except the past 15) this would have been considered an unimaginable “alternative universe.”

If easy money has made things murky (the results of mal-investment, over-leverage, excess concentration, euphoria-induced valuations, rapid disruption, etc.), investors should consider analyzing the world from a different perspective, from multiple vantage points. In addition to the tried-and-true valuations metrics: price to earnings, price to book value, price to cash flow, discounted cash flow, etc., all of which are impacted by the surreal quantitative easing (QE)-infused world, Kopernik has benefited from augmenting the analysis with Enterprise Value (EV) to sales, EV to break up value, EV to acres of land, EV to customers, EV to ounces/pounds/barrels/etc. of resource, and price to liquidation value. Analyzing things from multiple vantage points helps to avoid frauds and assists efforts to avoid value traps.

Invert, Always Invert

Inverting DCF (discounted cash flow) models into IRR (internal rate of return) models is technically a subset of the previous topic, but its importance warrants a separate discussion. As active managers, we are most excited when we discover areas where the crowd appears to be making a mistake. We’ve been talking about this for some time and believe it has created the likelihood of significant potential returns.

Per Investopedia:

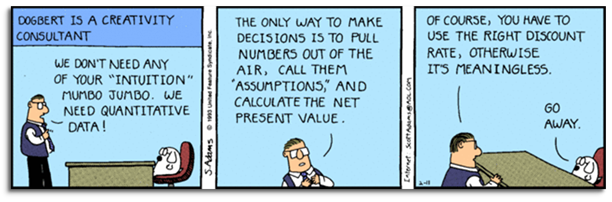

This is a very useful model and is indispensable for fixed-income analysis. Equities are different animals, and we’ve been arguing for years that in the “through the looking glass” era of QE, its usefulness has waned, if not completely disappeared. As someone once put it, it’s like the Hubble telescope (although I guess it should be updated to Webb): it zeros in precisely, but if your inputs are off slightly, you end up in the wrong galaxy. With that in mind, it’s worth examining the inputs to the model. Importantly, all the inputs are guestimates about the future. The future is always murky, but never more so than a post-the-QE decade. Will the massive accumulation of debt prove to have “borrowed” growth from the future? How much were profit margins “flattened” by low-interest rates and the shenanigans that accompanied them? How bad will the hangover be from all the malinvestment that was enabled? Should discount rates be low because rates are suppressed or do the probable higher inflation and likely write-offs of bad decisions mandate higher discount rates? As mentioned, a small tweak to discount rates makes a world of difference. A ‘galaxy’ of difference?

Kopernik inverts the DCF model to an IRR model. Replacing guesses about the future with appraisals of current inherent worth, we invest at large discounts to that worth and analyze returns of time. We are happy to discuss this in detail.

“There isn’t a single formula.

You need to know a lot about business and human nature and the numbers…

It is unreasonable to expect that there is a magic system that will do it for you.”

-Charlie Munger

Thoughts on the Current Environment

As complex, dynamic and interesting as bridge is, it doesn’t hold a candle to the financial markets. Actions affect behavior; behavior affects the markets. When something works for a long time, everyone embraces it; eventually they become infatuated with a system/method/trend. That very process begins sowing the seeds for the destruction of that methodology. It is not news that Kopernik is excited that the apparent overextension of some major investment trends, including financial assets, the U.S., growth stocks, index funds, and private equity has paved the way for massive outperformance by some important areas of underinvestment. These include real assets, international stocks (especially EM), value stocks, active managers, and certain areas within public equities. Life is cyclical. We hereby put forth the idea, or at least the hope, that the current dominance of win-at-all-cost ideology over stoic virtues, has about run its course.

We don’t fully disagree with the prevailing wisdom that the current era of big government and politically driven and controlled central banks favors the rich and powerful. Certainly, the divergence of fortune between the top 1% and the rest has been well-documented and abundantly reported on. Investors seem to believe that a new, quasi-feudal system has emerged that strongly favors those companies that have access to the deluge of money that has been printed and to the powers within government. These include a “consecrated” and concentrated group of companies within technology, pharmaceuticals, private equity, venture capital, defense, and banking. To invest anywhere else is just silly. We tend to agree with these thoughts, with the notable exception of that last point.

For starters, as this quip by the well-known stoic, Seneca, points out, it is usually silliest to invest with the crowd, not against. The evidence was clearly fervently supportive of stocks in the innovative late 1920s, and of quality growth stocks (Nifty-Fifty they were called) in the early 1970s, Japan in the late 1980s, technology in the late 1990s, financials in the mid-2000s, and of the aforementioned anointed group of the current mania. The subsequent losses were formidable in all the previous instances. Good fundamentals don’t mean good investments. Price matters.

Secondly, Marc Faber, and others, have discussed the “end game” of the winner-take-all economy. As the rich and powerful take from the masses, they increase their wealth and power immensely. But, when approaching a saturation point where the masses don’t have meaningful wealth left, the rich and powerful need to turn on each other. Under the feudal example, once all the land has been doled out, an ambitious lord would need to convince the king to favor him at the expense of another lord. At what point in time do the anointed take on the anointed? Google vs Microsoft? Amazon vs Apple or Alibaba? Pfizer vs Lilly? BlackRock vs Black Stone vs KKR, Carlyle, the others? The potential for lower profit margins deserves some mindshare.

Thirdly, and most importantly, even if the deck is stacked in favor of the anointed companies, there is plenty of money to be made investing in the incredible bargains that have been cast aside by the spellbound masses. Many great companies, valuable assets, needed products, and stores of value are disdained by the adrenaline junkies in search of more exciting stories. Value, which simply means buying things for less than they are worth, empirically has worked for centuries. It’s unlikely to have stopped working now, at least on this side of the looking glass.

The Case for Value Investing includes a Case for Values

Have the virtues espoused by Aristotle, and embraced (though tweaked) by the stoics become antiquated over the years, or does their endurance suggest they are well-founded? Kopernik believes that Wisdom, Courage, Justice, and Temperance are as important as ever. Furthermore, they are imperative to good investing. Let’s start with wisdom, an assertion that few would disagree with.

In this data-driven and “data-dependent” world in which we live, there is no shortage of knowledge. Wisdom is about making sound decisions based upon that knowledge. It is about understanding the world around us and putting aside our own judgments and preconceptions in order to see the world for what it is. We recommend studying Charlie Munger’s mental lattices, and behavioral economics, using the methodologies discussed earlier in this paper, and above all, getting out and seeing the world oneself. It is so often much different than we’ve been led to believe.

In stoicism, courage is about standing up for what is right, even when it’s difficult or unpopular, and staying true to our principles in the face of opposition. This trait is unfortunately often in short supply in the investment business. Most of us in the investment business are smart, diligent, informed, and hard-working. Therefore, these are not competitive advantages but merely requisites for the job. Not panicking at the bottom, not succumbing to FOMO (fear of missing out, aka greed) at the top and, most importantly, doing the right thing for client portfolios even when doing so is unpopular (to the point of jeopardizing one’s career) is the key to successful investing, in our opinion.

Cicero believed that “justice is the crowning glory of the virtues.” Kopernik believes, perhaps naively, that during the 1980s and 1990s, and possibly the 2000s, the rule of law was improving around the world. For global investors, the figurative wind was at our backs. More recently, there’s increasing evidence that the rule of law has been breaking down everywhere. Trust in governments and institutions is at historically low levels. We bring this up, not to moralize, but to suggest that investing is all about trust. Paying multiples of estimated future cash flows implies faith in the future and an expectation of fair dealing. If we are correct, investors may start to prefer current inherent value to high multiples on future guesstimates and scarce money to money of which future value depends upon the integrity of politicians. Stay tuned.

Temperance, the fourth virtue, is particularly interesting to us now. Investors currently are exhibiting little patience. They want their cash flow immediately. Ask them to wait a few years and they will forego prospective doubles. This is allowing investors to own scarce, life-sustaining commodities at bargain prices.

Conclusion

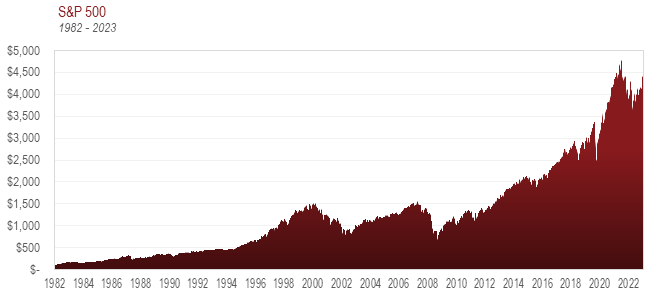

Thanks for allowing us to wax philosophical. This should be understandable in this truly extraordinary market. As this goes to press, the Nasdaq 100 is up 44% for the year-to-date, despite falling earnings expectations. This contrasts with the ACWI Value index’s 6.4% gain, as its earnings hit all-time highs. Certainly, as was the case in 1972 and 1999, this sort of bifurcation should cause one to contemplate.

Several years back it would have been hard to imagine a stock market going up in the face of interest rates at 5% and rising, money supply shrinking (somewhat) in the U.S., a de facto war with Russia in the Ukraine, tense relations with China, falling earnings, extremely unpopular presidential candidates from both parties, $2 trillion deficits as far as the eye can see, and many of the issues referenced above. Caveat emptor.

There are many ways to invest. The world favors the big companies, the connected companies. Things look good for them. There are numerous managers that will buy these stocks for you. This may prove to be successful. We will leave those stocks to the big and connected managers. As active, value-focused managers, we believe that the best time for our strategy is when few others even bother trying to assess inherent value. We believe that there have been few times in history where people were less focused on valuation. This bodes well. As was the case in 1999, we wish the growth investors well but expect that it will be hard for them to keep up with the returns that current fundamentals portend for value stocks. We remind people that the last time prior to the four decades of falling interest rates, the best returns came from agriculture, metals, energy, and emerging markets. Fundamentals appear to be equally supportive now. Fortunately, those are the areas that are deeply discounted in today’s market. We are thrilled with the quality of the companies and the attractiveness of the valuations in the portfolio. We believe that our moderate size and adhesion to stoic virtues will serve us well.

Thanks for your continued support,

David B. Iben, CFA

Chief Investment Officer

July 2023

“Remember that reputation and integrity are your most valuable assets

and can be lost in a heartbeat.”

-Charlie Munger

“Always take the high road, it’s far less crowded.”

“You need patience, discipline, and agility to take losses and adversity without going crazy.”

I just stumbled upon an article about “The Dress.” The viral internet meme from 2015 about the photograph of a dress that 57% of the population see as blue and black while 30% see it as white and gold.

It may come as no surprise – I see GOLD 😊

Important Information and Disclosures

The information presented herein is proprietary to Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is not to be reproduced in whole or in part or used for any purpose except as authorized by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell any product or service to which this information may relate.

This letter may contain forward-looking statements. Use of words such was “believe”, “intend”, “expect”, anticipate”, “project”, “estimate”, “predict”, “is confident”, “has confidence” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are not historical facts and are based on current observations, beliefs, assumptions, expectations, estimates, and projections. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to risks, uncertainties and other factors, some of which are beyond our control and are difficult to predict. As a result, actual results could differ materially from those expressed, implied or forecasted in the forward-looking statements.

Please consider all risks carefully before investing. Investments in a Kopernik strategy are subject to certain risks such as market, investment style, interest rate, deflation, and illiquidity risk. Investments in small and mid-capitalization companies also involve greater risk and portfolio price volatility than investments in larger capitalization stocks. Investing in non-U.S. markets, including emerging and frontier markets, involves certain additional risks, including potential currency fluctuations and controls, restrictions on foreign investments, less governmental supervision and regulation, less liquidity, less disclosure, and the potential for market volatility, expropriation, confiscatory taxation, and social, economic and political instability. Investments in energy and natural resources companies are especially affected by developments in the commodities markets, the supply of and demand for specific resources, raw materials, products and services, the price of oil and gas, exploration and production spending, government regulation, economic conditions, international political developments, energy conservation efforts and the success of exploration projects.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. There can be no assurance that a strategy will achieve its stated objectives. Equity funds are subject generally to market, market sector, market liquidity, issuer, and investment style risks, among other factors, to varying degrees, all of which are more fully described in the fund’s prospectus. Investments in foreign securities may underperform and may be more volatile than comparable U.S. securities because of the risks involving foreign economies and markets, foreign political systems, foreign regulatory standards, foreign currencies and taxes. Investments in foreign and emerging markets present additional risks, such as increased volatility and lower trading volume.

The holdings discussed in this piece should not be considered recommendations to purchase or sell a particular security. It should not be assumed that securities bought or sold in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of the securities in this portfolio. Current and future portfolio holdings are subject to risk.