Money (Dec 2023)

The marketplace believes, almost unanimously, that economic weakness causes less inflation. We believe this tenet to be way off base, leading to tremendous investment opportunity (and, conversely, peril).

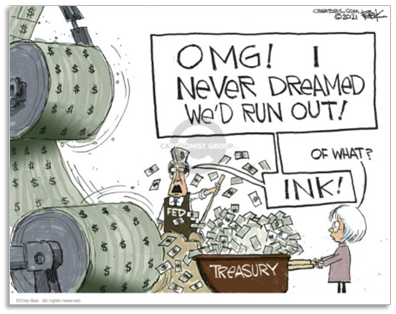

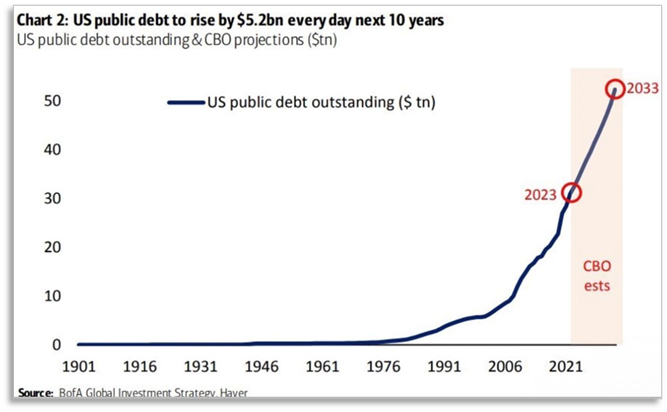

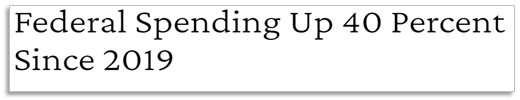

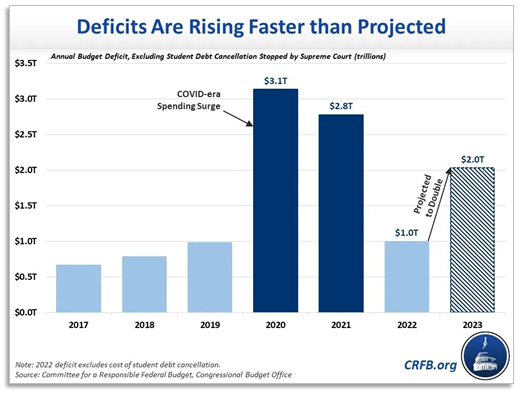

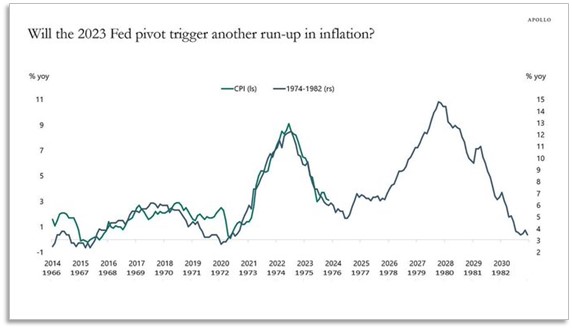

Yes, the CPI is rising at a slower rate and may continue to do so for a while. This is highly unlikely to last because the major governments of the world are a fiscal mess. In a nutshell, excessive spending incurs debt. Debt maintenance (in populist systems that can’t stomach austerity and borrow in their own currency) requires the conjuring of incremental money. Increasing money stock is the very definition of inflation. Therefore, excessive fiscal spending is inflationary. The U.S. alone is spending $2 trillion more than it is taking in. This number is per annum, during times of relative economic prosperity and peace. This monetary inflation finds its way into the prices of goods and services over varying times and magnitudes. For the long version, read on.

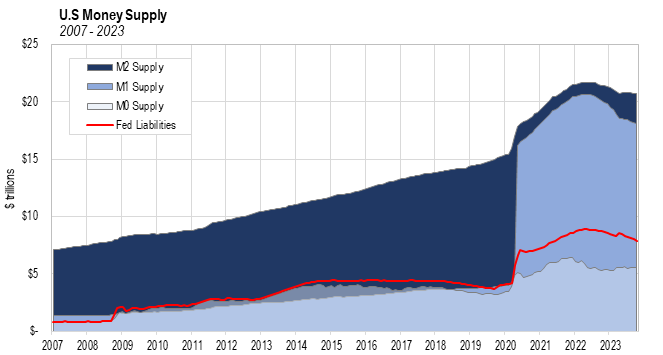

Post the recent trillion-dollar reduction in the money stock, supply is still up tenfold over the past 20 years. This recent reduction of money and concurrent evidence of a slowing economy is leading people to celebrate the end of inflation and the return of the “Goldilocks economy.” We believe this is a dangerous development. We’ve written repeatedly over the past three years about the Cantillon Effect, the premise that money is non-neutral, and thus, monetary inflation is not transitory but migratory, drifting from one asset/service to another, over differing timeframes and amounts. In this commentary, we take a step back to discuss the essence of money: what it is and why it matters.

“Money, get away

Get a good job with good pay and you’re okay

Money, it’s a gas

Grab that cash with both hands and make a stash

New car, caviar, four star daydream

Think I’ll buy me a football team

Money, get back

I’m all right Jack keep your hands off of my stack

Money, it’s a hit

Don’t give me that do goody good bullshit

I’m in the high-fidelity first class traveling set

And I think I need a Lear jet”

-Pink Floyd

The song “Money” was a big hit for Pink Floyd back in 1973, from their Dark Side of the Moon album, which sold over 34 million copies. There are numerous hit songs about money, many of which have their lyrics scattered throughout this missive. It is fair to guess that money may be the second most represented theme in songs, though it remains far, far behind love. It is clearly a topic that is very dear to many people. On Wall Street, even a hint of future “money” conjuring sets off a manic reaction. A recent issue of Almost Daily Grant’s relays the news that the mere conjecture that the Fed is done tightening and will resume printing next year led to the strongest market in more than three decades (based upon a standard 60/40 (stock/bond) portfolio which was up 9.6% during November). Generally, the more speculative an investment, the better the November and December (to date) returns. To get a sense for the magnitude of the Pavlovian response to the mere mention of more money, take a gander at the November/ December returns for the NASDAQ, ARKK, the Goldman Unprofitable Tech Stock index, or the plethora of crypto currencies.

“Did I hear you say that there must be a catch?

Will you walk away from a fool and his money?

If you want it, here it is, come and get it

But you’d better hurry ’cause it’s goin’ fast”

-Badfinger (McCartney)

Let’s start by admitting that, like most everyone else, we are fans of money. Pink Floyd quotes the commonly repeated idea that “money is the root of all evil.” The quote has mutated over the years from the original, “the love of money is the root of all kinds of evil.” Kopernik believes that a better way to view money is as a horrible master but an excellent servant.

“Come on, come on, love me for the money

Come on, come on, listen to the moneytalk”

-AC/DC

An obvious starting point is by defining this thing called money. A quick perusal of the internet quickly makes it clear that this is less simple than one might suspect. There are varying definitions of money, which in and of itself is thought-provoking, but Wikipedia captures the gist of what is generally taught in economics classes:

“Money is any item or verifiable record that is generally accepted as payment for goods and services and repayment of debts, such as taxes, in a particular country or socio-economic context. The primary functions which distinguish money are as a medium of exchange, a unit of account, a store of value and sometimes, a standard of deferred payment.”

That is what we were taught, but if it sounds simple – think again. For example – “not so fast” say economists of the Austrian persuasion. Being a medium of exchange is the only requirement of money. Few forms of money are good stores of value or are consistent units of measure. By that definition, few things qualify as money, and they tend to be woeful mediums of exchange. Are they correct? We’ll come back to this, but first let’s look at other points of contention.

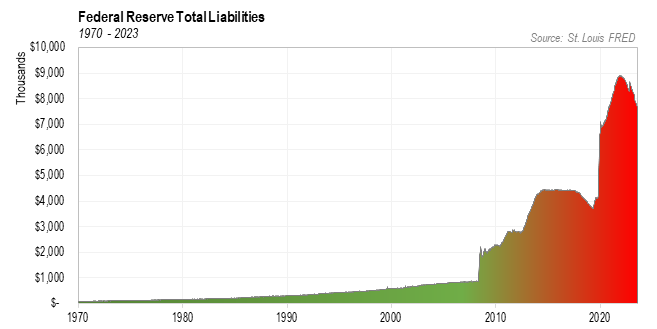

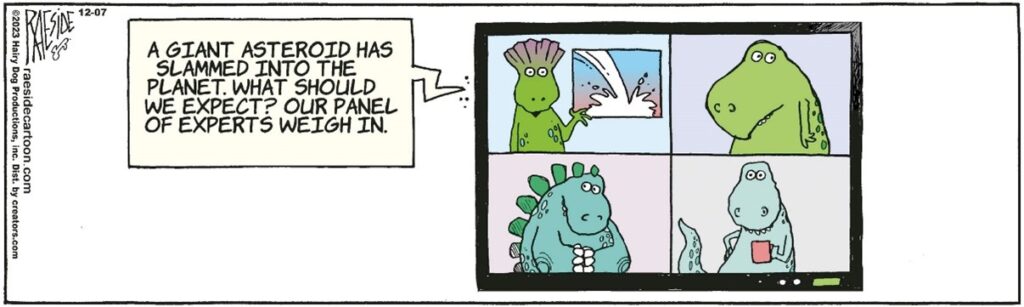

A little analysis yields an interesting point – when it comes to the subject of money, experts don’t agree and often aren’t even in the same ballpark. There is a plethora of proponents supporting the following definitions of money: the U.S. dollar (which isn’t so simple because it alone can be measured using M4, M3, M2, M1, M0, Fed liabilities), many of the other sovereign fiat currencies, gold, other hard assets, bitcoin, other cryptocurrencies, and probably infinite others. It’s not so easy and multiple definitions are defensible.

As a quick aside, throughout history, many different things have served as money, including seeds, seashells, copper and other metals, and of course precious metals. Below is a picture that I took at the Museo del Banco Central in Buenos Aires, highlighting the history of money, including the use of seeds and seashells, among other things. Certainly, the Argentine central bank is second to none in understanding the consequences of unsound money.

At Kopernik, we believe that gold is the least imperfect form of money, but that isn’t the point here. We live in a dollar-based world. It is currently the reserve currency, most commodities trade in dollars and many investment returns are dollar denominated. For purposes of this discussion, we will accept the Austrian view and use the dollar as money. Lest you think we are selling out, please understand that the valuable point that we hope to make is that, while it isn’t important what we call money, it is imperative that we are prepared and properly invested for a world in which fiat money is failing. Opportunity and peril are both abundantly present.

The Seismic Change of Monetary Debasement

One of the first things taught in macro-economics is the Quantity Theory of Money (QTM), which states that the price level is determined by the amounts and speed of money in circulation and the volume of production. The erroneous formula MV=PQ is the standard in use. The formula has been slammed by the recently discredited disciples of modern monetary theory (MMT; those believing that there are few constraints to the amount of debt and money that sovereigns can summon into being). We, at Kopernik, find the MV=PQ formula flawed but the underlying concept that nominal economic growth is a function of money growth to be both self-evident and empirically proven throughout history. As our eponym, Copernicus, observed a half-millennium ago, “we in our sluggishness, do not realize that the dearness of everything is the result of the cheapness of money. For prices increase and decrease according to the condition of the money. An excessive quantity of money should be avoided.” The idea was later popularized by John Stuart Mill, Irving Fisher, and of course Milton Friedman and Anna Schwarz, amongst others. The formula’s attempt to capture a real concept is flawed for multiple reasons, most notably because “PQ” (Price times Quantity) omits many of the most important real world factors: stocks, bonds, private equity, venture cap, cryptocurrency, art, and real estate (captured, but quite inaccurately). It is in these very items where many of the symptoms of the contemporary, inflationary, tenfold increase in the money stock can be found. “V,” representing velocity, is a solved for variable, meaning it changes to whatever is necessary to make the formula both technically correct and ultimately useless. And the variable “M” represents “money” and is the topic at hand.

As prefaced earlier, in recognition that we still live in a dollar-based world, it is the quantity of dollars that belongs on the left side of the QTM equation, while goods and services, which importantly include hard assets, stocks, bonds, collectibles, and crypto, belong on the right side of the equation, as variables that are price-dependent upon the increase in dollars. Perhaps the equation should be M=PQ′, where M equals quantity of U.S. dollars (base money) and Q′ is the quantity of all goods and services (eliminating the self-serving V).

In other words, as Copernicus observed so long ago, growth in the supply of money increases the nominal size of the economy. Increases above the growth of quantity will lead to higher prices.

Having thus, in our opinion, vastly improved the formula, it is important to make another valuable observation. Since economics is so imprecise, small to medium sized changes to independent variables shouldn’t be taken too seriously, but seismic changes should command attention. The past 15 years has been a major quake.

As an aside, I may have mentioned in the past how my attitude toward economics has evolved over time. Feeling smug after acing a tough upper division class, I was devastated when the professor summed things up on the last day, “remember all the assumptions that we made back on day one? None of them apply in the real world!” That, combined with my experience in the real world (watching people’s errant fixation on small changes in M1 in the early 1980s) caused me to temporarily dismiss all belief in macro-economics. However, watching the events in 1980s-Japan and 1990s-TMT (technology, media, telecom), I came to realize that when things get way out of whack, it is time to take notice; logic will eventually prevail. 2008, 2021, and recent events solidify this premise. Following a tenfold increase in the monetary base, and the hint of more to come, this commentary seems timely. While we prefer M0 or Fed liabilities as the best measures, almost any measure of the quantity of dollars is off the charts. It is time to pay attention!

“Money don’t get everything it’s true

What it don’t get, I can’t use”

-Barrett Strong (Berry Gordy, Jr)

Sticking with the Austrian view that money needs only to be a medium of exchange, the dollar’s success has probably been superior to anything in all of history, especially in its current, mostly digital form. The pound, yuan, yen, euro, franc, etc. are all excellent media of exchange as well. All are readily accepted at most stores within their countries and, of course, by the issuing governments. But while fiat currencies, as money, are excellent media of exchange, one worries whether people have become too complacent about money’s inability to function as a “store of value.” This important trait is where fiat currencies have always failed in the past. Given the tenfold increase in the Fed’s balance sheet between 2008 and 2021 and the ongoing MMT (modern monetary theory) mindset in Washington (and globally), one must give serious consideration to the possibility that the dollar will fail spectacularly as a reserve currency, and a store of value, in the future. While focus here is on the U.S. dollar, it should be understood that most of the points apply fairly equally to all of the world’s major currencies.

Wikipedia continues with:

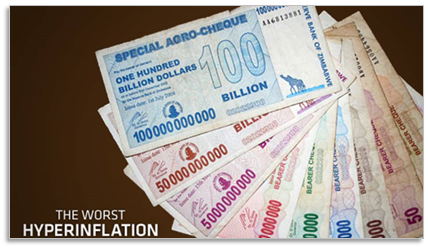

“Money was historically an emergent market phenomenon that possessed intrinsic value as a commodity; nearly all contemporary money systems are based on unbacked fiat money without use value. Its value is consequently derived by social convention, having been declared by a government or regulatory entity to be legal tender; that is, it must be accepted as a form of payment within the boundaries of the country, for “all debts, public and private,” in the case of the United States dollar. Contexts which erode public confidence, such as the circulation of counterfeit money or domestic hyperinflation, can cause good money to lose its value.”

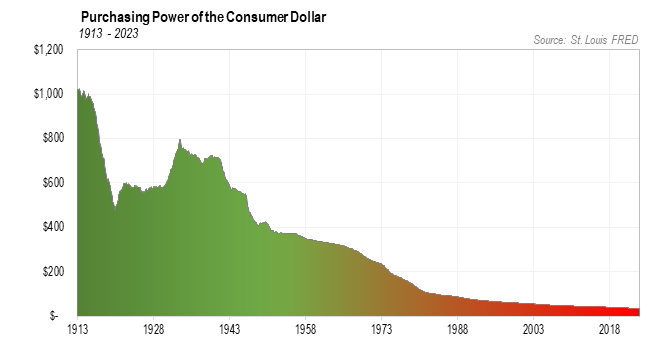

And lose value, the dollar certainly has. The charts below show that, as theory and logic predicted, it lost value in lockstep with the increase in the supply of dollars.

Yes, we are experiencing a drop in money supply now, but it is important to note that there have always been pullbacks but the broader trend is always upward. The table below shows that despite 8 years of decline, including the largest drop ever this year, the increase over the two decades was almost tenfold!

“You never give me your money

You only give me your funny paper”

–Beatles (McCartney)

And this 98% loss of purchasing power occurred during the “good times,” when the U.S. “empire” was the primary beneficiary of two world wars and developed the most prosperous economy and mightiest military every known. What might the rate of devaluation be in a QE-infinity world?

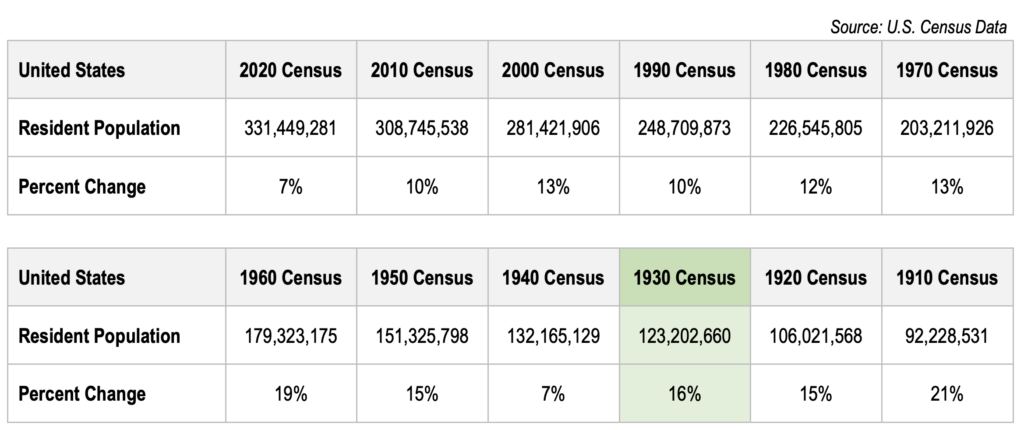

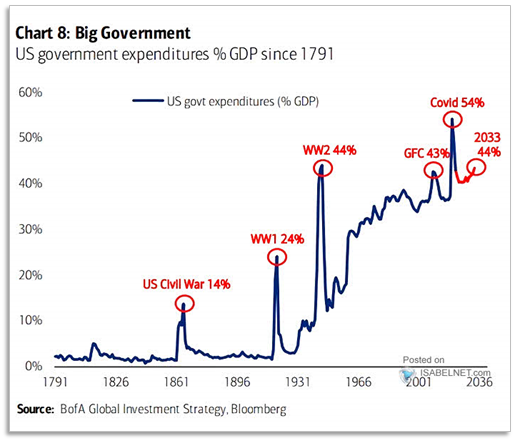

Granted, the fact that the U.S. experienced massive currency devaluation over the past three-quarters of a century is ancient history. Furthermore, it is often said that inflation is caused by growing populations or economic growth. Although it’s a widely held view, history and logic resoundingly state otherwise. It is said that people ignore history at their own peril. And regarding the hopes for economic growth panacea, we suspect that people are “majoring in the minors.” While growth can pressure the price of goods a little higher over the short term, the “big picture” point is that major inflations are always associated with very weak economies: Holland (1634), France (1795), Weimar Germany (1923), China (1935-49), the Soviet Union (1917-24), Hungary (1945), Venezuela (2013) and many other Latin American countries over the past century, Zimbabwe (2006), Armenia (1993), Yugoslavia (1944 and 1994), and so on. These were all associated with bad economies, often in the aftermath of war or popping of market bubbles. Meanwhile, the deflationary 1930s occurred during one of the fastest periods of population growth in U.S. history. Inflation is a monetary phenomenon, nothing more.

Closer to home, the purchasing power of the dollar has been quickly waning even prior to the QE turbocharging.

The Effects of Monetary Debasement

The point to be taken here is that since inflation is a symptom of fiscal profligacy (rather than of estimates of GDP or population growth), current fundamentals subject investors to great peril. Fortunately, they also have an opportunity to figuratively turn lemons into lemonade – or perhaps Dom Perignon? It is worth noting that those celebrating the recent return to disinflation are making a serious mistake by confusing a second derivative with a first derivative. While the rate of change has decelerated during 2023, the trend continues to be higher, as it has for every calendar year since 1954 in the United States. Rising prices, not deflation, is the historical norm.

“Perhaps it is one secret of their power that, having studied the fluctuations of prices, they (bankers) know that history is inflationary, and that money is the last thing a wise man will hoard.”

― Will Durant, The Lessons of History

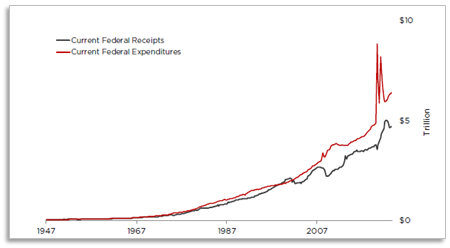

Furthermore, reckless fiscal policy invariably leads to spurious monetary policy. Regarding the likelihood of upcoming fiscal prudence, it is fair to point out that no major political parties in any major country espouse balanced fiscal budgets. Deficit spending is the lay of the land. Let’s look at fiscal policy, past and present, to further understand why this matters:

The aforementioned lemons represent the fact that inflation (as measured by CPI) has gone up every year for 70 years, money supply has increased tenfold over the past 15 years, fiscal deficits are at breathtaking levels (rarely seen without a recession or major war), and the will to eliminate deficits is seemly nonexistent worldwide. What would you say if an investor proposed to you the idea that a potential security would lose 98% of its value over the coming decades? Presumably, they’d be tossed out on their ear. But that is what has happened to holders of U.S. dollars over the past three-quarters of a century. In all likelihood, the next three-quarters century will be more of the same, at best. Jim Grant has pointed out that if the Fed achieves its 2% annual debasement goal, prices will rise nearly five times during an average person’s lifetime. In other words, 80% of their purchasing power will be eviscerated. The information below lends credence to the idea that actual results could be much higher than their 2% target.

“Oh, why do I live this way?

(Hey, must be the money!)”

-Nelly

And this projection is sans recessions. It should be clear that inflation is a likely part of our future.

“We think we know what we’re doin’

That don’t mean a thing

It’s all in the past now

Money changes everything”

-Cyndi Lauper (actually Tom Gray)

Having hopefully established that fiat currencies, with all of their positive attributes, can’t be trusted to maintain the value of our savings, and that this reality is unlikely to change in the near future, it’s time to move on to investment strategy.

Investment Strategy

As mentioned above, the lemons investors have been given can be turned into lemonade by those who recognize that while inflation hurts many investments it turbocharges others.

It is said that there are times to worry about return on capital and a time to worry about return of capital. Having established that a decade of zero interest rates and other malicious policies have created a “bubble in everything,” and that these high prices are especially misaligned with the decreasing stability of the world, it appears our current situation is a time to focus on return of capital. Furthermore, given the plethora of evidence of the two-thirds of a century decline of the dollar’s purchasing power, and the likelihood of much more to come, perhaps the old adage should be restated as, “there are times to ramp up one’s purchasing power and times to protect oneself from succumbing to erosion of purchasing power of one’s savings and investments.” We suggest that the bulk of one’s assets should be invested accordingly. We offer three suggestions below, the first of which focuses on maintaining purchasing power, while the second two detail ways that some of one’s portfolio could be positioned to yield significant gains, in nominal and real terms.

- Own Stores of Value. A debasing currency provides a backstop for real investments, driving their prices up over time in nominal terms. This has been addressed above, so we won’t rehash it here other than to reiterate that companies that have products and services that people need (as opposed to merely want), and have decent barriers to entry are best positioned to pass through pricing pressure and thus prove to be able to maintain their value.

“Tell me that you want the kind of things

That money just can’t buy

I don’t care too much for money

Money can’t buy me love”

–Beatles (McCartney)

- Be a Discerning Shopper. A debasing currency migrates through the system, affecting prices unequally, at different rates and times. (This is addressed in our forthcoming sister commentary – Don’t Cry for Me Argentina, and in our multiple commentaries on the Cantillon Effect.)

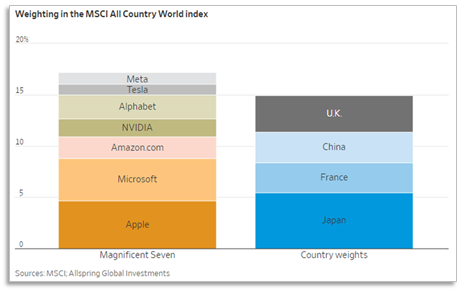

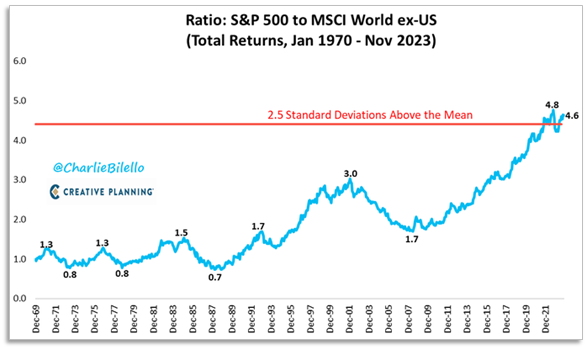

For example, if you own the popular ACWI (All-Country World Index), you have more invested in the seven most popular U.S. stocks than in the world’s 2nd, 4th, 6th, and 7th largest economies combined. That should make clear how askew the current valuations are. Industry by industry (with the exception of natural gas), bargain shoppers find it well worth the effort to shop beyond the U.S. border.

- Demand large, asymmetric potential returns, within a portfolio that is diversified across currencies, countries, sectors, industries, and management teams. (addressed below)

To compensate for abnormally high level of risk caused by lax monetary and fiscal policies

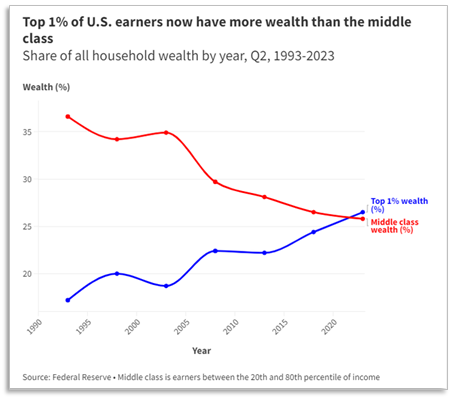

Money-printing increases risk in two obvious ways – by causing prices to get dangerously high and by tempting many into spurious investment prospects. Less obviously, it undermines society. By increasing inequality, and weakening the rule of law and moral underpinning, monetary inflation increases global tensions, class-warfare, and graft at the corporate and government levels; it leads to increasing concentration of power. For those who are interested in the support of this assertion, please refer to the appendix. We’ll spare the rest of you.

Returning to the investment implications of the current political ethos, the bad news is that risks are much more daunting now than they have been for decades. The much better news is that in this extremely bifurcated market, investors have seemingly priced 200% of the negatives into the valuations of many stocks (even as they accord 200% of the positives into their favored investments). This is very important. This means that the upside, when the risks don’t come to fruition, is twice as lucrative as it ought to be. This amounts to highly positive asymmetries of returns. For more discussion about risks and why they are best viewed on a portfolio level, please refer to the appendix.

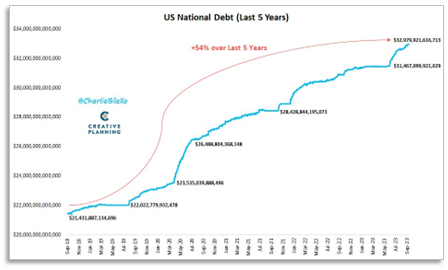

And since money printing is the almost certain aftermath of deficit spending, it should be clear that inflation should be top of mind for all investors. CPI is not inflation, merely a poor measure of certain symptoms of inflation’s effects in the consumer sector. So far, the symptoms of inflation continue to mostly reside in the financial sector, i.e. bull markets. History and logic dictate, and 2022 gave us a glimpse, that inflation will migrate from stocks and bonds into the broader economy. As to deficit spending, the U.S. government estimates $2 trillion (with a T) of deficits annually for the foreseeable future; worse if a recession hits or geopolitical conflicts continue to escalate. U.S. National Debt is now up a massive $1.5 trillion since the debt ceiling “crisis.” Over the last 3 months alone, the U.S. has added $500 billion PER MONTH to the national debt, on average. Over the last 5 years, U.S. debt is up a whopping 54%. Meanwhile, YTD interest expense just passed $800 BILLION.

We suspect that, á la the Nifty-Fifty circa 1972, today’s popular stocks will likely inflict larger than normal losses on investors for the reasons already discussed. And if not, the potential returns will prove unrewarding. But following many years of value stock prices lagging behind fundamentals in promising areas within emerging markets, energy, foods, industrial metals, and precious metals, the potential upside from here far exceeds the downside. This is accentuated by the fact that there has been a long period of under investment in capacity and that the tenfold increase in money supply is still in the early innings of working its way through the system. That portends very positively stacked returns in these industries over the next decade. Kopernik portfolios are currently amply invested in these well positioned areas. In addition to being quite attractively valued, we believe the portfolio offers highly asymmetric upside potential, substantial protection from inflation, exceptionally large margins of safety, and diversification across companies, industries, currencies, management teams, and countries. This is not the case for the popular indices. For more information on why we are excited about the prospective asymmetric returns of specific holdings, please refer to our other writings on our website or contact us.

We feel very fortunate as we enter 2024 because we see so many opportunities. The companies best positioned to do well during inflationary times are inexpensive enough to potentially outperform meaningfully even sans inflation. The volatile nature in which price increases roll through the system (just as Cantillon predicted) scares those who view it as risk but excites those who see opportunity. The misperception and resultant mispricing of securities during times of fiscal and monetary malfeasance has created the prospect of significantly positive asymmetric returns. We are thankful for the opportunity to serve you during these interesting times. Happy Holidays to all.

Cheers,

David B. Iben, CFA

Chief Investment Officer

December 2023

Appendix

The Case for Larger Margins of Safety

Permit me to issue and control the money of a nation, and I care not who makes its laws!

-attributed to Mayer Amschel Rothschild

The plan is to state the obvious, while drawing upon other commentators, having a little fun with this serious topic, and hopefully avoiding any “preachiness.” There is a lot of theory to suggest that manias resulting from excessive credit always have their “morning after.” As Ludwig von Mises said, “There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as a result of voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion, or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.” Obviously, easy money leads to rising market valuations, which in turn cause complacency, if not downright carelessness, on the part of investors. But beyond the obvious investment implications, there are broader, more consequential ramifications. Money printing also leads to greater levels of inequality, which often leads to societal problems. It is said that currency debasement leads to debasement of society. None of the political winds, globally, over the past four years rebut this theory.

Debasement of Society

Before getting into various quotes and theories, let’s step back and frame the discussion. Assuming one was to offer bribes to people if they were to commit a specific crime, what level of success might they have? For a $10 bribe, one can hope they would find very few takers. $100 might gain more than a few takers, whereas $1,000 would probably be eye opening. $1 million would likely demonstrate that the majority of humans have a price. $1 billion is a breathtaking number that I imagine few could resist. With that in mind, it should be clear that the corruption surrounding $1 trillion is probably worse than any of us can comprehend. The $4 trillion that the Fed and Treasury conjured out of thin air during 2020, and handed out to those of their choosing probably led to more corruption than anything else in recorded history. Worse, that $4 trillion was the icing on the $9 trillion-dollar cake. From 1913 until early 2008, almost a century, the Fed created less than $1 trillion. The magnitude of what they have printed since is staggering. It is understandable that students of history have been successfully predicting the current plethora of distrust, unrest, breakdown of the rule of law, concentration of power, and spike in global tensions. Certainly, these developments deserve the attention of all investors.

It is interesting that contemporary Neo-Keynesians approve of current policymaking. It is doubtful that Keynes himself would be amused, as illustrated by his famous quote below.

In 1921 he said:

“By a continuing process of inflation, Governments can confiscate, secretly and unobserved, an important part of the wealth of their citizens. By this method they not only confiscate, but they confiscate arbitrarily; and, while the process impoverishes many, it actually enriches some. Those to whom the system brings windfalls…become “profiteers” who are the object of the hatred…the process of wealth-getting degenerates into a gamble and a lottery. Lenin was certainly right. There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.”

It is also interesting that Lenin, a notorious communist, seems to have understood monetary theory better than the PhDs of today.

Here are various comments from others on this disturbing subject.

“At its most fundamental level, SocGen’s Dylan Grice notes that economic activity is no more than an exchange between strangers. It depends, therefore, on a degree of trust between strangers. Since money is the agent of exchange, it is the agent of trust. Debasing money therefore debases trust. Grice emphasizes that history is replete with Great Disorders in which social cohesion has been undermined by currency debasements. The multi-decade credit inflation can now be seen to have had similarly corrosive effects. Yet, central banks (repeatedly) continue down the same route. The writing is on the wall. Further debasement of money will cause further debasement of society. Dylan, like us, fears a Great Disorder.”

So says Tyler Durden (www.zerohedge.com) in edited excerpts from an article on his site entitled From Currency Debasement To Social Collapse: 4 Case Studies

Dylan Grice says, “And now the social debasement is clear for all to see. The 99% blame the 1%, the 1% blame the 47%, the private sector blames the public sector, the public sector returns the sentiment…the young blame the old, everyone blames the rich…yet few question the ideas behind government or central banks…I’d feel a whole lot better if central banks stopped playing games with money…All I see is more of the same – more money debasement, more unintended consequences and more social disorder. Since I worry that it will be Great Disorder, I remain very bullish on safe havens.”

“We have replaced the government and values of the American Framers’ Constitution with something shockingly different that we call ‘The Machine’,” says Craig Smith. “The Machine includes our mostly unelected ruling elite widely called the ‘Deep State.’ It includes the Federal Reserve, the unelected regulatory bureaucracy and opinion-shapers, our entangling globalist commercial and military alliances, and the Military-Industrial Complex that President Dwight Eisenhower warned us about in his chillingly prophetic 1961 Farewell Address.”

“Today Eisenhower would warn about the Military-Industrial-Financial Complex, because during the Clinton Administration the giant banks and related financial institutions replaced military contractors in a quiet coup d’etat and now are who our politicians look to for political campaign contributions,” says Ponte. “Hillary Clinton has good reasons she won’t release transcripts of the three short speeches for which financial giant Goldman Sachs paid her $675,000.”

While this quote focuses on Hillary, we note that both parties seem to be equally under attack for similar conduct. And of course, this is not a U.S.-only phenomenon.

“Money, it’s a crime

Share it fairly, but don’t take a slice of my pie

Money, so they say

Is the root of all evil today”

-Pink Floyd (Roger Waters)

From Marc Faber’s excellent Gloom, Boom, Doom February 2020 monthly commentary: “In last month’s report, I discussed Patrick Barron’s essay ‘The Hidden Link between Fiat Money and the Increasing Appeal of Socialism’. I explained that I hadn’t fully understood, until recently, that QE programs nurture and foster socialism, interventionism, and the expansion of governments’ involvement in the economy. What I forgot to mention is that ‘free money’ in the ‘wrong hands’ can also lead to militarism and imperialism. Ludwig von Mises explained the consequences of inflation presciently.

‘Inflationism, however, is not an isolated phenomenon. It is only one piece of the total framework of politico-economic and socio-philosophical ideas of our time. Just as the sound money policy of gold standard advocates went hand in hand with liberalism, free trade capitalism, and peace, so is inflationism part and parcel of imperialism, militarism, protectionism and socialism.’”

We’ve quoted Charlie Munger often in these commentaries. He had such a great mind and would have turned 100 years old next month. As was his style, the following quote is short and to the point:

And when pools of capital are made more accessible to some parties than others, many believe that money begets power, which begets money, which begets more money… It does appear that the Citizens United case back in 2010 has presented a good case study of the phenomenon. Presidents Washington, Jefferson, Hoover, and Eisenhower, among others, warned against allowing concentration of power.

“When there is a lack of honor in government, the morals of the whole

people are poisoned.”

-Herbert Hoover

If you run short of money I’ll run short of time

If you’ve got no more money honey I’ve got no more time

If you’ve got the money honey I’ve got the time

We’ll go honky tonkin’ and we’ll have a time

-Lefty Frizzell- Perhaps anticipating U.S. Congressmen in the 21st century

“I don’t believe the price of gold

The certainty of growing old”

-Don Williams

Perhaps most disturbing is the following quote which can’t be completely dismissed out of hand.

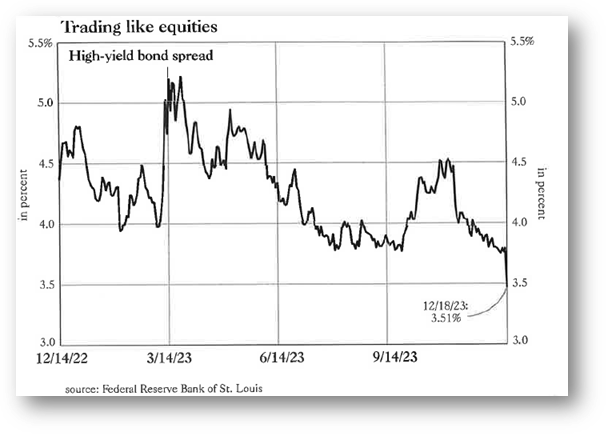

Not cheery thoughts. But, hopefully this hasn’t come across as a sermon, but rather as a reminder that investments are about trust; they are about belief in the future. A high PE (price relative to earnings) suggests that one is confident enough in the future to base decisions on earnings that won’t happen for quite some time. Low interest rates suggest that investors are confident that the currency of which a bond is denominated won’t be significantly debased in the future and that the issue will have the willingness and wherewithal to repay the money. Tight credit spreads indicate that investors are extremely confident of repayment.

Then there is the international picture. A previous commentary of ours made the case that the indebted “problem children” of yesteryear (the “PIGS”) are quickly being overtaken by the current problem children (the JIGS UP, Japan, Italy, Greece, Singapore, United States, and Portugal). It is amazing to see how comfortable investors have become with the formerly disdained PIGS. It remains to be seen when they will care about the rapidly declining fundamentals of the JIGS.

Therefore, in a world where the public is exceptionally unhappy with politicians on both sides of the aisle, trust is very low for the media, corporations, government, and academics. Where the central banks and governors don’t even pretend to care about responsible monetary or fiscal policy, it seems odd that prices for securities don’t reflect this lack of trust. Au contraire, valuations in this recently returned “bubble in everything” are near the most daunting ever.

If there was ever a time to focus on the return of purchasing power; on margin of safety; on outsized returns on successful investments, that would seem to be now. Speaking of which, the next section of this appendix briefly addresses the beauty of diversified positive asymmetry.

“You’ve had enough, you ship them out

The dollar’s up, down, you’d better buy the pound

The claim is on you

The sights are on me

So what do you do

That’s guaranteed”

-AC/DC

“Talk me into losin’ just as long as I can win

I want the easy

Easy money

Easy money

I want the good times

Oh, I never had”

-Billy Joel

“Oh there ain’t no rest for the wicked

Money don’t grow on trees”

-Cage the Elephant

Diversified Asymmetric Returns

When “risk” is underpriced investors should be excited

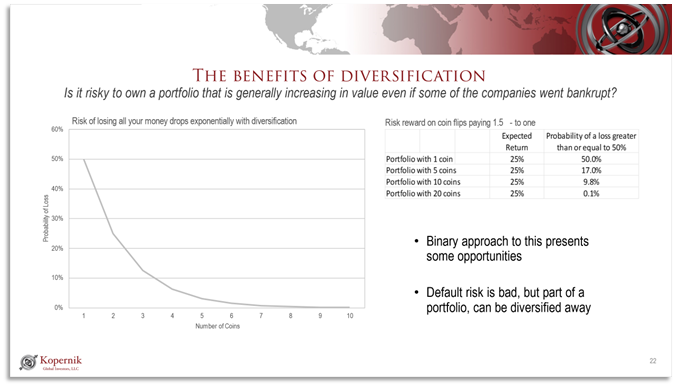

Diversification is an interesting topic. Some believe that it is an important part of risk management while others deride it as “deworsification.” Which is more accurate? Like most things, details and thought are required for the answer. A diversified portfolio of overpriced things will be just that – overpriced, and hence – risky. A portfolio of underpriced and uncorrelated securities portends good future returns with a level of risk that falls as the number of holdings (diversification) increases.

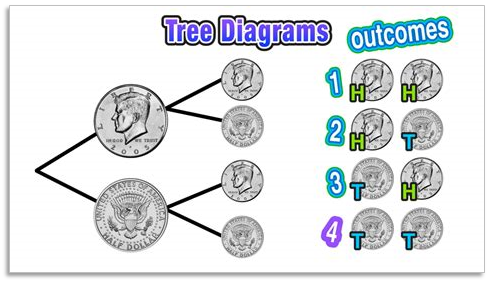

By way of example, if one were to wager on the flip of a fair coin to come up heads, there is a 50% chance that they will lose. The prospect of losing one’s money half the time is disconcerting, however, if the odds are strongly in one’s favor, the bet should be made. If tails cost $100, then heads deserve a $100 profit ($100 profit plus return of the $100 bet + $200 payoff). Half the time $100 would be won and half the time it would be lost. Now suppose that tails still costs $100 but the payoff for heads was increased from $200 to $300 ($200 profit plus return of the $100 wager). On average, the winnings would be $150 (winning $300 half the time and $0 half the time), hence an expected return of 50%. The good news is that the expected return is great; the bad news is that on a single coin flip there is a likelihood of a complete loss. Opportunities like this demonstrate the beauty of diversification. Given a two flip “portfolio” the odds of losing money fall from 50% to 25%. There are four possible outcomes (HH, HT, TH, TT). Only TT (tails on both flips) results in a loss ($200), while one of each lead to a $50 profit and HH leads to a $400 profit.

Eight flips reduce the odds of losing money to 14%. Three or more heads is profitable. With 50 or more-coin tosses, the probably of losing money is less than 1%.

Certain sectors of the stock market offer an even better deal than these advantaged coin flips. The odds of an adverse outcome (equivalent of tails) in the market is much less than 50% and the upside to our estimates of the upside when advantageous outcome (figurative heads) is much better than 150%. When it comes to emerging markets and “latent value” stocks, investors seem to have it backwards, believing that adverse outcomes are the norm. Due to their mass misconception, the marketplaces offer lucrative payoffs, in many cases more than $400 payback on our $100 investment. As the crowds rush to bet on tails, the smart investor will invest in an outcome of heads. While one flip of the coin is risky, two things are noteworthy: expected returns are still outstanding on a risk-adjusted basis, and as part of a diversified portfolio of similar but independent flips, the amount of risk quickly approaches zero, as the number of flips increases.

To summarize, diversification of attractively valued, uncorrelated securities effectively eliminates risk, while allowing for the attractive returns to be captured. The stock market offers much better prospects than the illustrative coin flips. The expected upside on many of our stockholdings are in the range of 4x, plus/minus, while the odds of a large loss are likely way less than that of a coin flip. We’ve found that losses have been rare over the past four decades. Please call with questions.

Important Information and Disclosures

The information presented herein is proprietary to Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is not to be reproduced in whole or in part or used for any purpose except as authorized by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell any product or service to which this information may relate.

This letter may contain forward-looking statements. Use of words such was “believe”, “intend”, “expect”, anticipate”, “project”, “estimate”, “predict”, “is confident”, “has confidence” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are not historical facts and are based on current observations, beliefs, assumptions, expectations, estimates, and projections. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to risks, uncertainties and other factors, some of which are beyond our control and are difficult to predict. As a result, actual results could differ materially from those expressed, implied or forecasted in the forward-looking statements.

Please consider all risks carefully before investing. Investments in a Kopernik strategy are subject to certain risks such as market, investment style, interest rate, deflation, and illiquidity risk. Investments in small and mid-capitalization companies also involve greater risk and portfolio price volatility than investments in larger capitalization stocks. Investing in non-U.S. markets, including emerging and frontier markets, involves certain additional risks, including potential currency fluctuations and controls, restrictions on foreign investments, less governmental supervision and regulation, less liquidity, less disclosure, and the potential for market volatility, expropriation, confiscatory taxation, and social, economic and political instability. Investments in energy and natural resources companies are especially affected by developments in the commodities markets, the supply of and demand for specific resources, raw materials, products and services, the price of oil and gas, exploration and production spending, government regulation, economic conditions, international political developments, energy conservation efforts and the success of exploration projects.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. There can be no assurance that a strategy will achieve its stated objectives. Equity funds are subject generally to market, market sector, market liquidity, issuer, and investment style risks, among other factors, to varying degrees, all of which are more fully described in the fund’s prospectus. Investments in foreign securities may underperform and may be more volatile than comparable U.S. securities because of the risks involving foreign economies and markets, foreign political systems, foreign regulatory standards, foreign currencies and taxes. Investments in foreign and emerging markets present additional risks, such as increased volatility and lower trading volume.

The holdings discussed in this piece should not be considered recommendations to purchase or sell a particular security. It should not be assumed that securities bought or sold in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of the securities in this portfolio. Current and future portfolio holdings are subject to risk.