Optionality (Jul 2024)

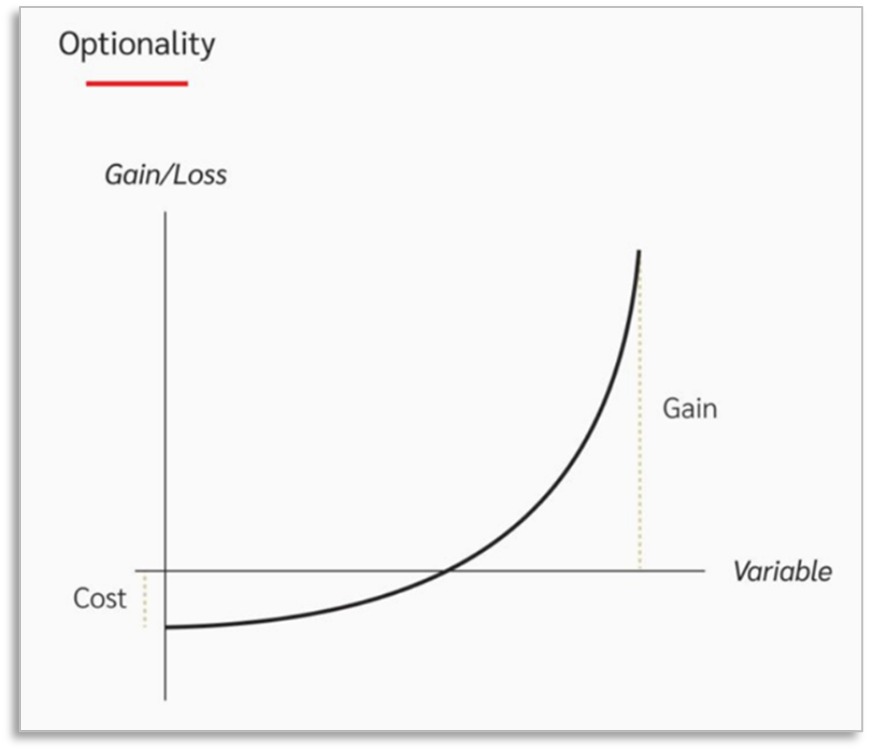

Mitigating portfolio risk in potentially volatile times via positive asymmetry

A math-lite discussion of why optionality is advantageous.

In this commentary, we juxtapose current valuations with the record high levels of risk in the economy and financial system, suggest that this fragile state of affairs requires an “antifragile” portfolio, and conclude with a discussion of asymmetry and the role of options and optionality in an antifragile portfolio.

“If you start from the premise that we are living in an uncertain world,

then optionality is the only way to outperform the average over the long run.”

-Nassim Taleb

“Risk means more things can happen than will happen.”

-Elroy Dimson

“All investing consists of dealing with the future, and the future

is something we can’t know much about.”

-Howard Marks

Uncertainty is the only certainty in life (except for death and taxes). As Elroy Dimson said, “More things can happen than will happen.” From an investor’s perspective, some things will be bad, but not all of them. Our main message here is that this situation, while undoubtedly creating risk, creates bountiful opportunities as well. Good things can happen too. The investment strategy that outperforms in the long run is one that is hurt minimally when things do not go as expected and benefits greatly when things work out in our favor. This is an antifragile strategy.

An antifragile strategy has optionality. Optionality, at its core, means having options, choices, different paths to success. Options, but, importantly, not obligations. Choices can be agonizing, but it is better to have agonizing choices than to have no choices at all. It is generally understood that optionality in life is a good thing, and that we should strive to increase it. We can increase our optionality by getting an education, staying out of debt, having a variety of skills, or any number of other choices. When one has options, one can limit the downside if things in life don’t go as planned, with the potential for great upside if they swing in one’s favor.

It is interesting that investors don’t demand the same of their portfolios. In fact, many investors end up building portfolios with negative optionality. At the extremes in the market, investors tend to extrapolate the past into the future indefinitely and fail to imagine any change of course. Valuations, as a result, need the status quo to continue.

Investing with the trend can be successful for a while. (It has been successful longer than any of us at Kopernik would have expected!) Of course, just because a wager is a poor one doesn’t mean that it will lose. Sometimes one can win repeatedly but eventually (predictably) the unpredictable strikes. A wiser strategy is the subject of this whitepaper. Investors should look to put themselves in a situation whereby they will be successful in many potential futures. It is not prudent to put all the eggs in one basket, especially in an environment that could move in extreme ways. How will technological innovation, unprecedented monetary policy, and changing geopolitical relationships disrupt the status quo? Like anything, there will likely be many exciting outcomes, and many unfortunate ones. Since we’ll undoubtedly have volatility in our future, options are nice to have.

As it goes with our investment process at Kopernik, options and optionality must be undervalued to be attractive investments. Thankfully, once the crowd does not see the need to hedge their optimism, patient, humble, and disciplined investors are able to buy optionality for a very cheap price; in some cases, for free.

“Confidence is a feeling, which reflects the coherence of the information and the

cognitive ease of processing it. It is wise to take admissions of uncertainty seriously,

but declarations of high confidence mainly tell you that an individual has constructed

a coherent story in his mind, not necessarily that the story is true.”

-Daniel Kahneman

Optionality helps manage uncertainties.

It has been well documented that humans, in general, abhor uncertainty. Humans make sense of a complex world through recognizing patterns, relying on intuition, and creating narratives. But while our biases, intuition, and mental shortcuts have helped us survive as a species, they can lead us astray as investors. Investors, particularly in the teeth of bull and bear markets, tend to use what Nobel prize-winning economist Daniel Kahneman refers to as System 1 level thinking (quick, instinctive and emotional), when they should be using System 2 (slow, deliberate and analytical). Investors tend to underestimate the role of chance and overestimate their ability to forecast. These tendencies (as well as many other cognitive biases) got investors into trouble in 1929, 1973, 1987, 2000, 2008, and 2021, and we would argue, today. These were (and are) times of extreme confidence in the future. Investors have constructed a narrative, and the prolonged momentum market has reaffirmed their beliefs. Trouble lies ahead when the crowd piles into one story.

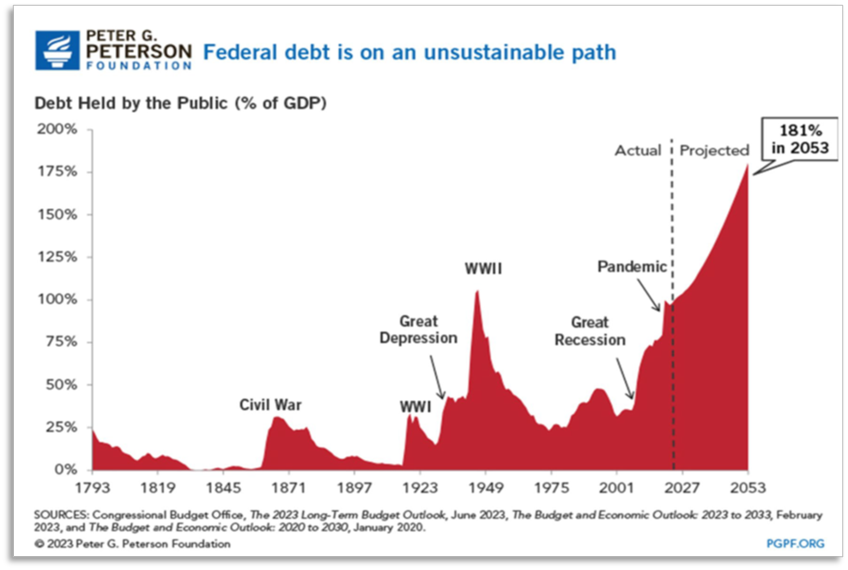

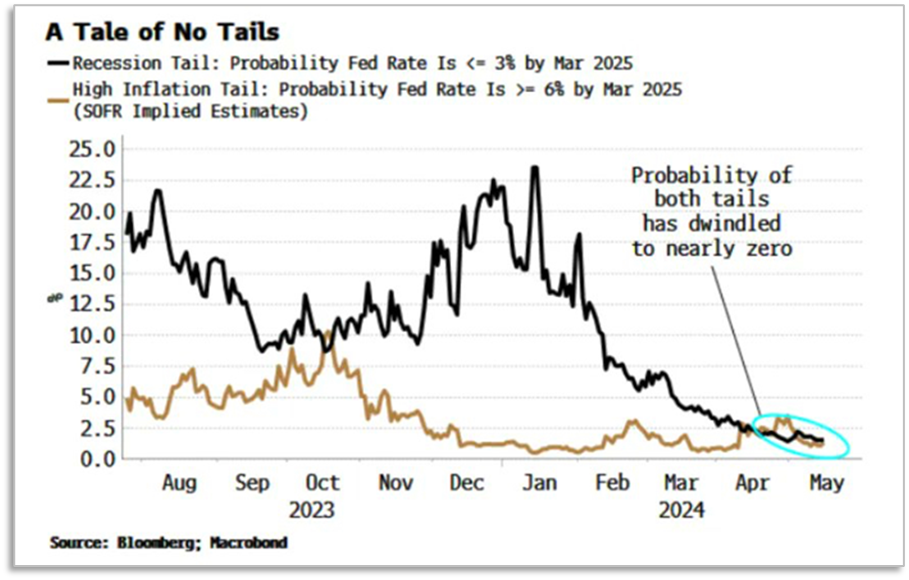

Today’s markets seemingly depend on things staying the course. U.S. GDP growth has been strong, but it has been propped up by an unsustainable amount of debt. For the current bull market not to fail, everything needs to be perfect: we need AI to be profitable, we need the Federal Reserve to ease while at the same time not fueling inflation, we need the government to keep propping up the economy without the bond market noticing the inflation. Quite a lot needs to happen—there is little room for error, or disorder.

And yet chaos, disorder, and volatility are the words of the real world. They are also the things that hurt fragile systems. Fragility depends on things following an exactly expected course. Therefore, when investors are spending countless hours of the day trying to figure out what the future will be, it is a fool’s errand. No one is good at forecasting. Investors should instead be determining how fragile a potential investment is. It is easier to determine fragility than it is to forecast the future. Ask yourself, “are you traveling on a highway with no exits?” If things don’t go as planned, are you going to have a rough year, or are you going out of business?

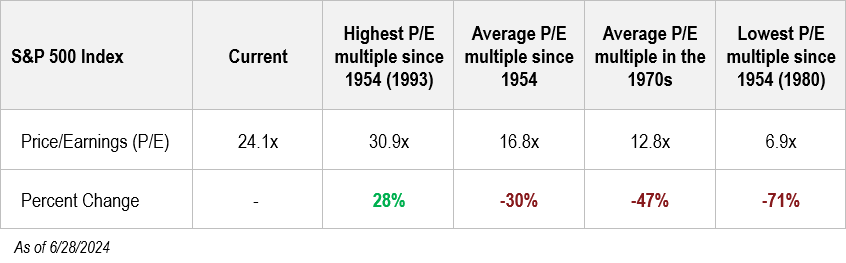

While anything can happen in the short term during a momentum market, what is the long-term upside if things go well? Comparatively, what is the downside if things normalize? Where is the asymmetry in today’s market? A glance at historic multiples gives us an idea.

Investors have put themselves into a fragile state and locked themselves into one future. But as Voltaire pointedly said, “Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is absurd.”

With certainty near peak levels, optionality is being mispriced. What follows is discussion on options pricing as well as market opportunities where options and optionality are significantly underpriced.

“Confidence is a feeling, which reflects the coherence of the information and the

cognitive ease of processing it. It is wise to take admissions of uncertainty seriously,

but declarations of high confidence mainly tell you that an individual has constructed

a coherent story in his mind, not necessarily that the story is true.”

-Daniel Kahneman

Optionality is mispriced. Prudent investors can benefit.

“Options, any options, by allowing you more upside than downside, are vectors of antifragility.”

-Nassim Taleb

A financial option gives one the right to buy or sell something at a price, for a certain period of time. The most one could lose is the premium paid, and one stands to gain multiples of their investment should things go in their favor. It goes without saying that everyone should want this sort of payoff diagram. Most of the time, however, options are too expensive. In fact, many smart investors have made a fortune selling options. Just like anything, price is paramount, and this includes options.

Black Scholes remains one of the most common models to price options. It is a scary looking formula, but the key inputs are quite intuitive. The 5 important drivers that increase the value of an option (from the perspective of a call option) are the following:

- Higher interest rates

- Increasing value of the underlying asset

- Lower strike price

- More Time

- Higher Volatility

Higher interest rates raise the value of an option; buying an option means putting up less capital up front, and the capital that is saved can generate interest. The higher the interest rate, the more that capital can generate elsewhere.

Increasing the value of the underlying asset also increases the value of the option as the right to buy at a given price is worth more. Similarly, a lower strike price allows the option-holder to garner more money at any given price of the underlying asset.

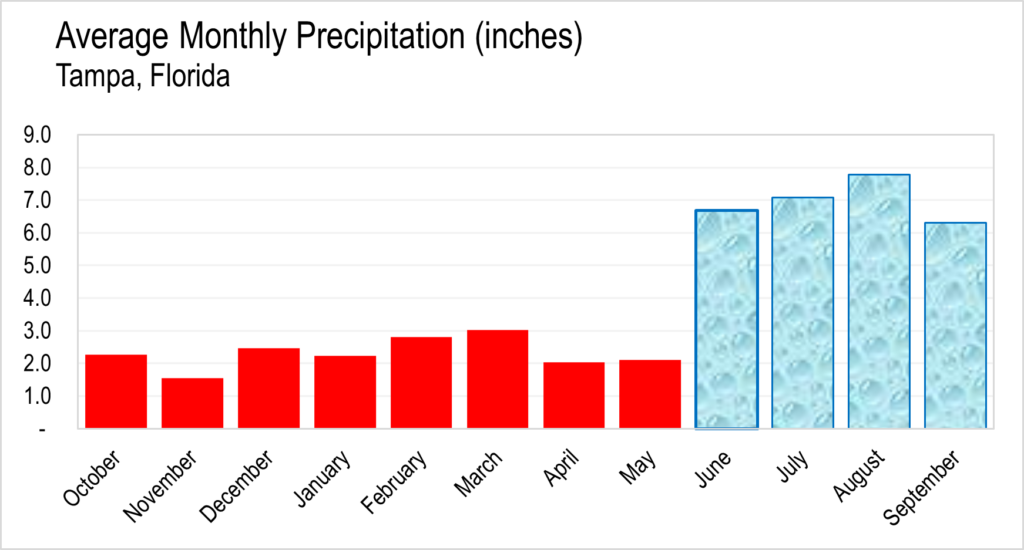

The two remaining, time and volatility, are important to explore further. In previous presentations, we’ve used a bet on the weather to illustrate these concepts. How much should one be willing to bet that it will rain 6” in one month in Kopernik’s home of Tampa, Florida? If one is sitting in October, the bet doesn’t look promising if it is for one, two, three, or even eight months:

But a yearlong timeframe is almost a sure thing. Thus, time has the alchemist’s property of turning something that was worthless into something very valuable. Time is our friend with options. The more time you have, the more time you have for things to change and your thesis to play out.

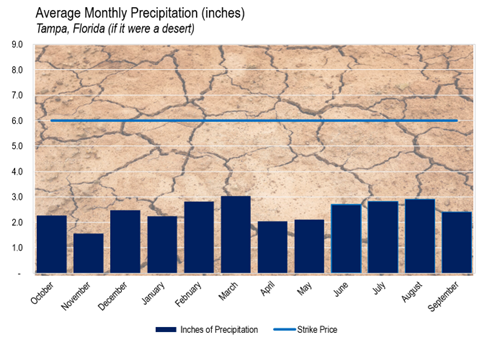

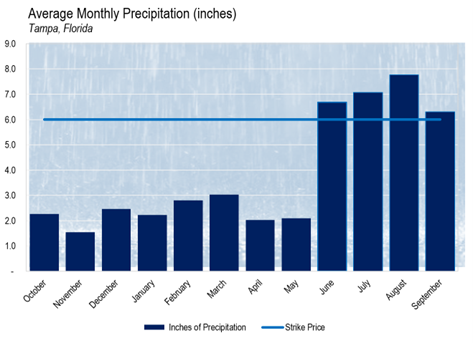

Volatility is another important driver of option prices. Let’s imagine that we make the same bet, but in a desert, where the average rainfall fluctuates between 2-3 inches year-round. There is no volatility, thus it is highly unlikely our bet of 6” is ever reached. More volatility increases the value of the option since the chance of the option expiring in the money is higher.

In a desert, such an option might be on sale cheaply, but it is not very valuable. But what if you could buy options from someone who thought they were living in a desert, but were actually living on a tropical island with a dry and rainy season?

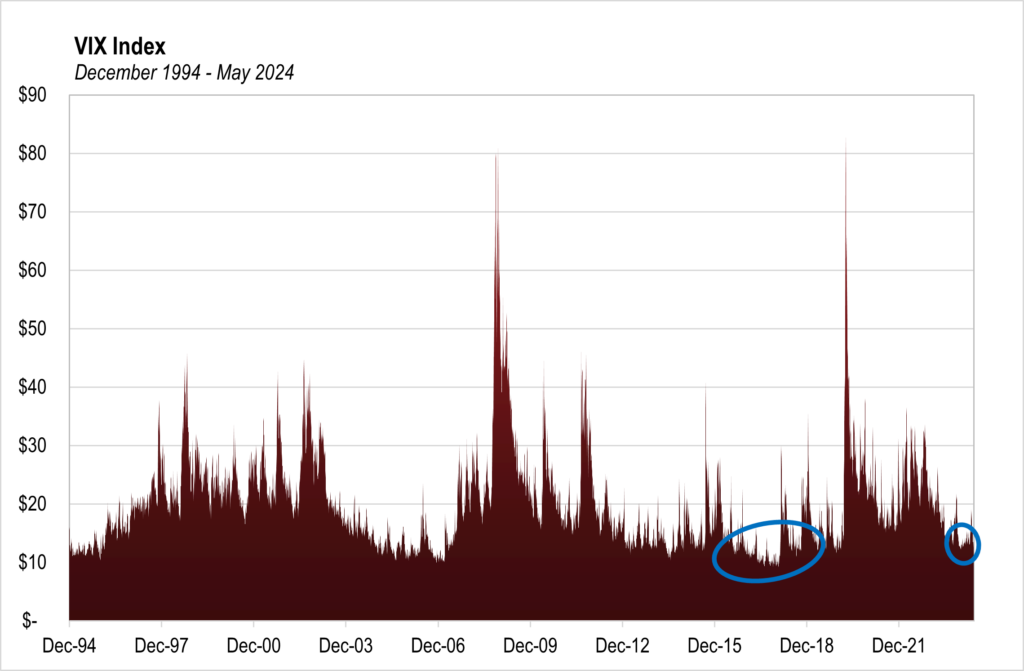

Hopefully you can see the connection to today’s market. The market today, with volatility near low levels, is saying that it doesn’t expect uncertainty or future volatility—implied vol is low, causing options to be cheap. At Kopernik, we have been buying put options on the S&P 500 Index on and off for the last seven years. In late 2017, we could buy options with implied volatility as low as 8. We lost premiums for several years as we rolled these options but made it all back in several weeks in 2020 when volatility spiked to above 50 and the index fell during Covid. That is the beauty of buying massively underpriced securities – over the long run, time works in one’s favor.

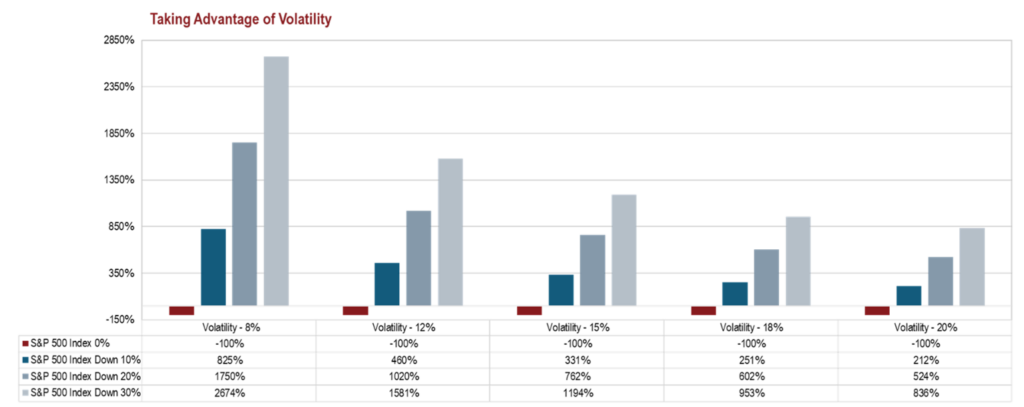

The table below shows the math for hypothetical implied volatility situations for a put option on the S&P 500 Index. Buying implied volatility cheaply buys time and increases the payoff. For example, if one were to buy an option with implied vol of 8%, that investor would break even or make money even if a market correction of 20% happened within 3 years; if the correction happened sooner, the return could obviously be large. On the flipside, if the implied vol is 20%, the correction would have to occur within 10 months and the return would be smaller. Thus, both options have antifragile payoffs – the downside is much smaller than the potential upside – yet the implied vol of 8% option has more optionality and is more antifragile.

The above scenarios are based on put options on the S&P 500. Inputs include a 2-month at-the-money option on the S&P 500 level of $5,123.41 as of 4/12/2024 and varying volatility levels. By varying the volatility levels, we impute an options price and can calculate the profit of the options based on differing level changes in the S&P 500 Index. In the S&P 500 Index 0%, this indicates a maximum loss of 100% of the premium paid for the options.[1] 1

“Risk never looks like risk when it’s generating a high return.”

-Howard Marks

Another important point—just because you buy an option does not mean that you have positive optionality. If the odds are not in your favor, and you are buying an option with high implied volatility, you are buying a very expensive security that is unlikely to play out and does not pay off enough for the risk taken. There are times to buy options and times to sell options. One popular trade now is shorting the VIX[2]2. On the surface, this might seem reasonable. (According to a recent edition of Jim Grant’s Almost Daily Grant’s, the S&P 500 has now gone more than 300 sessions without logging a single day 2% decline; the VIX has closed over 15 only twenty-one times in 2024 thus far—the three-decade average is near 20!) At current levels, we would argue that shorting the VIX is a fragile trade with negative optionality, since it likely will provide a lot of consistent gains until one day an event causes a complete wipeout of one’s capital: the equivalent of picking up dimes in front of a steamroller. Again, fragility is defined by how much you need something to follow an exact course. Those shorting the VIX need volatility to remain near lowest levels. If the markets start to price in less than utopia, their loss would be significant.

“The fool believes that the tallest mountain in the world will be equal to the tallest one he has observed.”

-Nassim Taleb

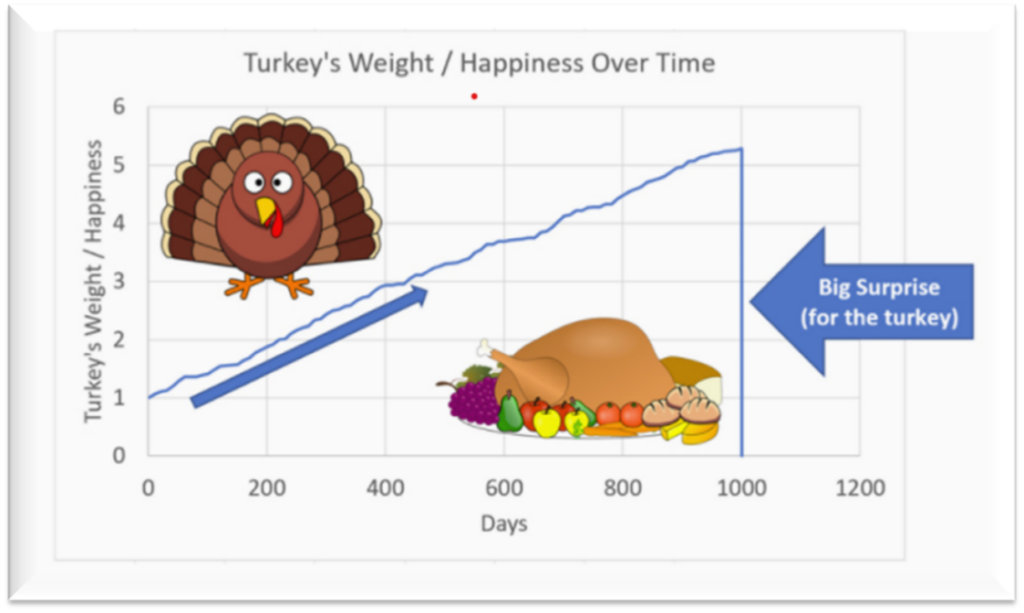

Investors suffer from a failure of the imagination that the future could look different from the past. The longer a trend has gone on, the greater the confidence that the trend will continue. It is like the proverbial Thanksgiving turkey, who every day receives food, water, and shelter from a nice farmer. For 999 days, the turkey is getting as much food as he can eat: daily evidence that the farmer is looking out for his best interests. The turkey’s confidence in the farmer is the highest right before Thanksgiving Day.

People tend not to prep for black swan events, or for disorder, or for a change in direction. Black swan events are by nature unpredictable, and we are unable to calculate the probability that they will happen, so many investors ignore their potential occurrence.

Eric Peters, CIO of One River Asset Management, relates a conversation that stresses the benefits of a different way of thinking:

“Why do people feel that to be a good leader, they must absolutely believe in one direction over another, one path over another, one person over another?” asked the investor, an allocator. “Why do most people feel they have to live in a world of absolutes?” We were discussing the illusion of certainty. “We live in a world filled with questions. And the best traders I’ve known have never been sure of anything.” The blessing and curse of this business is that it forces us to come to terms with how little we know. It is at once terribly humbling and awe inspiring, in that to maintain your balance you must continually seek to define a wide range of possible outcomes, possibilities. Which is an exciting journey, requiring imagination, and a recognition that world history is the story of chance, surprise.

“The most successful traders speak in probabilities of one thing over another. Not one dares pound the table and state something with absolute certainty. Something in our nature, or perhaps society, leads us to believe that to have gravitas we need to make grand pronouncements, appear definitive. Such statements are almost always wrong.” Yet we continue to listen, in a hopeless pursuit of certainty. “The best leaders amongst us seem to understand that their gift is not in pointing the way, it’s in taking input, maintaining flexibility, openness, adjusting enroute.”

To paraphrase Bruce Karsh, probable things fail to happen all the time, and improbable things happen all the time. Those who think they know the future are deluding themselves. Thankfully, the more delusional the crowd, the larger the opportunity set of positive asymmetric investments for patient, confident, rational investors. When the market loves one thing, it hates something else. When the money is all flowing to the top, other areas are ignored. Those market inefficiencies are where we find positive optionality.

We will spend the remainder of this whitepaper discussing the places where we see opportunities with positive optionality today. As we have discussed most of them elsewhere, we will be brief.

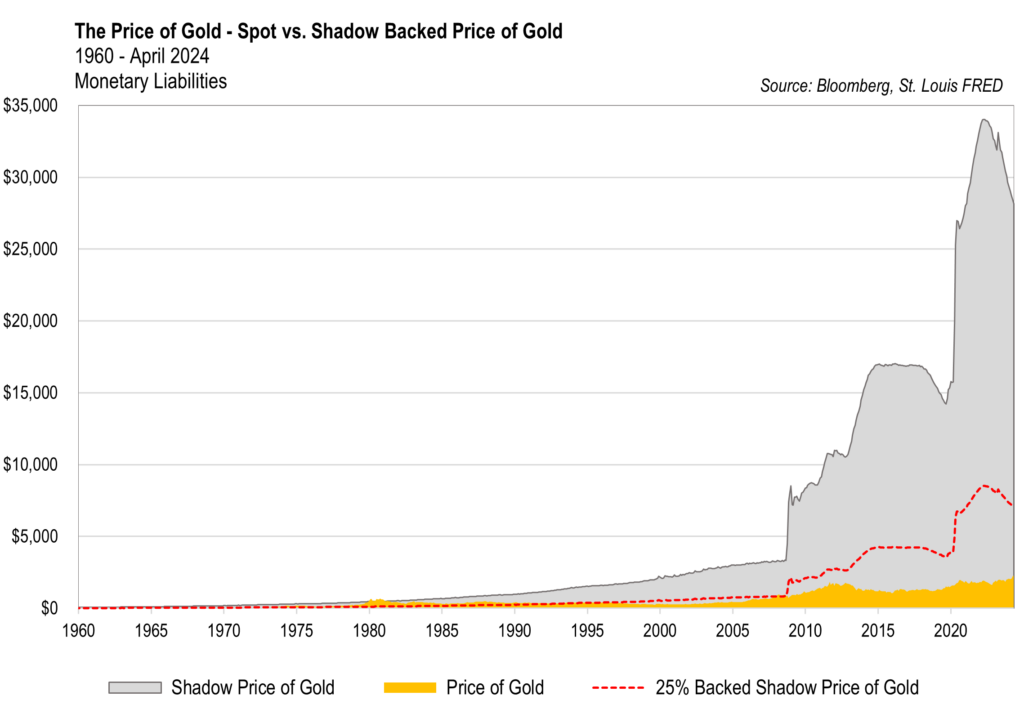

Gold

Let’s start someplace familiar to our readers—gold. As you likely have surmised from our previous writings and calls, we like the positive asymmetry in gold. Thousands of years of history show that gold is a good store of value; meanwhile, time has shown the exact opposite of fiat currencies. Over the long term, gold tracks the monetary base, yet this relationship has become distorted since 2008. In our opinion, the issue is not gold, but rather the absolute faith and trust in central banks. This faith is a decidedly cyclical phenomenon.

At Kopernik, we think of gold both as a commodity and as money, something we will discuss in detail in our forthcoming precious metals whitepaper. The gold price today is near its long-term incentive price (the price required to bring incremental production online) if it were viewed as a commodity, thus the downside risk is small. And from the perspective of gold being valued as money, there are numerous futures where gold could go much higher than it is today. The chart below shows how dislocated gold has become from the monetary base. We believe that gap will close.

While the fundamentals are positive for gold, gold miners offer substantially more positive optionality. The mining companies are akin to an option on top of an option. They are exposed to the optionality of gold and to the optionality that the ratio of gold miners relative to gold normalizes. There are further options as well: the possibility that the miners find additional ounces in the ground, that management teams engage in accretive transactions (yes, miracles can happen!), that technological advancements improve mining recoveries, etc. When it comes to miners, they are currently trading below what they are worth if prices stay the same and have the potential to be multiples higher if the gold price rises. Thus, they have limited downside with the status quo, and the possibility of outsized return should things change. This is the very definition of anti-fragile.

The companies with the most positive optionality are the resource-laden but non-producing companies that the market has left for dead. Why does this opportunity exist? We believe this to be due in large part to a misuse of the discounted cash flow (DCF) model in the mining industry. In our opinion, an optionality-based valuation model does a better job of capturing the value of the miners and does a much better job of valuing mining companies that are not in production. Please refer to our forthcoming mining whitepaper for an in-depth discussion.

Agriculture

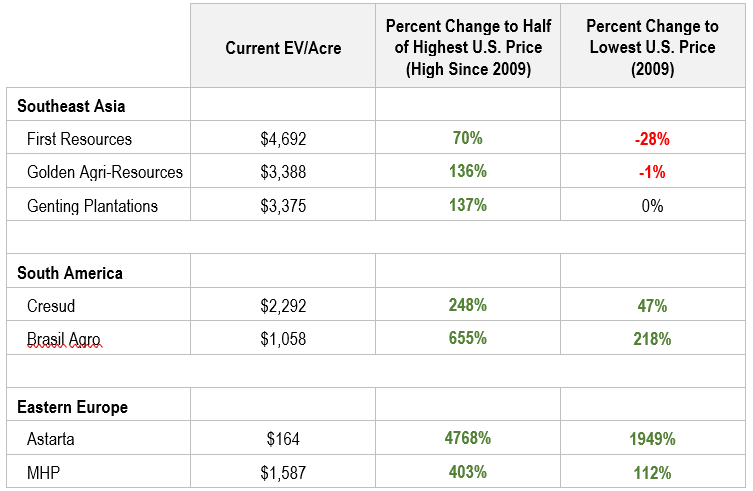

Like the gold miners, we value agricultural companies on their resources; in this case, their land. Agricultural land outside of the U.S. trades at a massive discount to land within the U.S. In some cases, land in emerging markets is trading well below where the U.S. traded back in 2009! It is difficult to imagine that land with some of the best topsoil in the world is worth a lot less than where the U.S. traded 15 years ago. Thus, the downside is protected while the upside is very significant. One can argue that EM land should not trade at par with the U.S., but even if we get halfway there, many of these companies are worth a lot more than they are trading at today.

Source: Bloomberg, Company Reports, Iowa Farm Bureau, Iowa State University

Iowa Low Price Since 2009 ($3,361/acre in 2009), Average Since 2009 ($10,886/acre), High (Also the Current as of 12/31/2023, $15,968/acre), Half of the Highest Price equates to $7,984/acre.

Emerging Markets

In addition to real assets, we see significant positive optionality in emerging markets domiciled stocks. We have discussed this at length elsewhere (see especially our February 2024 commentary Don’t Cry for Me Argentina), so we will not go into too much detail. The question to ask oneself is “what if the emerging market counterpart traded in line with (or even closer to) the U.S. counterpart? This isn’t an outrageous question. Many of these examples show that at one point in time, the emerging market company was preferred; now many have become seemingly uninvestable. Markets are famously cyclical.

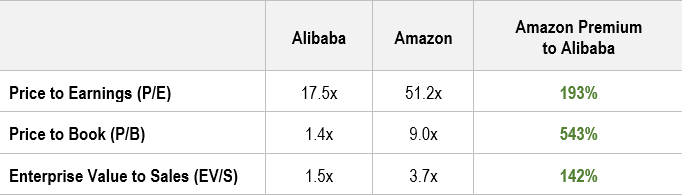

What if Alibaba traded like Amazon?

What if the Amazon of China traded like the U.S. Amazon? The companies were priced closely together for years, but they have diverged significantly. Alibaba has a 46% market share of e-commerce in China, compared to Amazon’s 40% in the U.S. There are certainly risks to investing in China—an uncertain economy and regulatory environment come to mind, as well as the probability that the country has already entered a recession. Perhaps the market’s dislike of China is a factor. What if sentiment on China changed? Might Alibaba come more in line with its counterpart?

Charts reflect the growth of $1000 for two or more comparable companies and do NOT reflect the performance of any particular stock within any Kopernik portfolio.

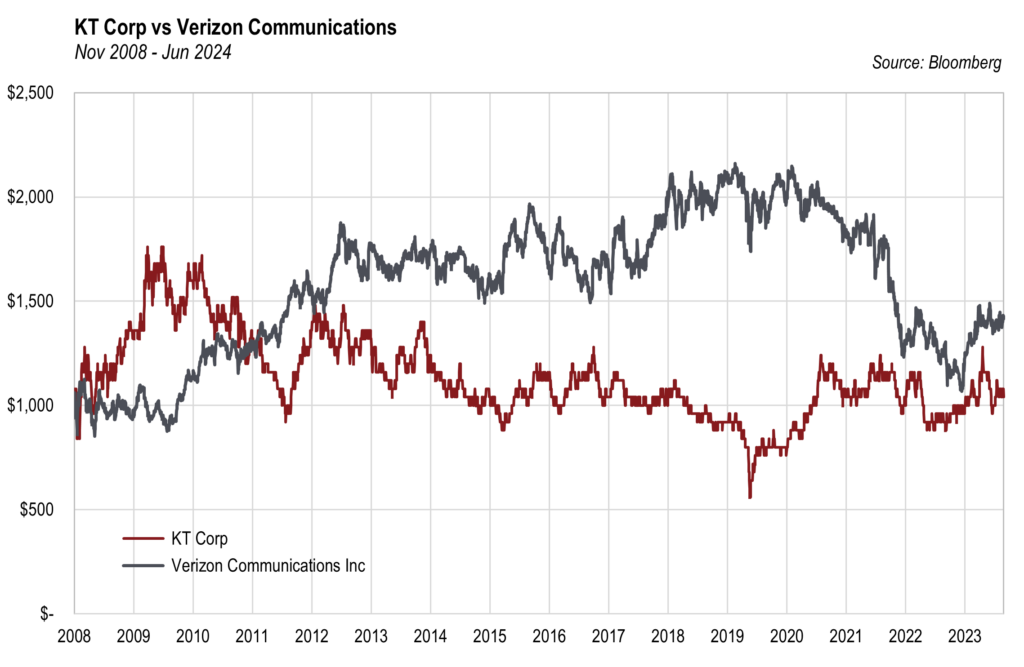

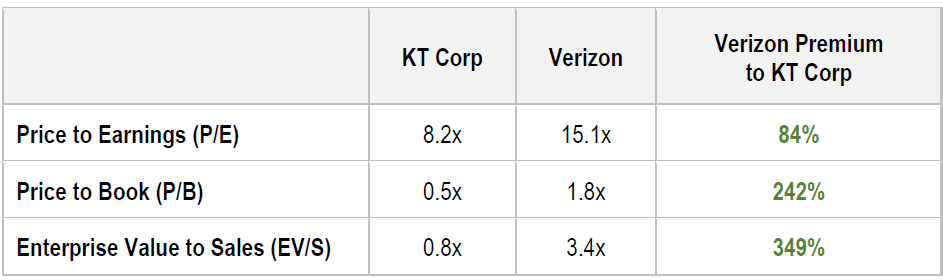

What if global telecom traded like the U.S.?

Studies have revealed that people would rather be separated from their spouse or their pet than give up their smartphone. Mobile phones have revolutionized how we communicate, whether through texting, social media, or video calls, and revolutionized how we access information—4.6 billion people around the world use mobile internet, and 4 billion of those people do so on a smartphone.[3]3 Yet telecom companies in the U.S. are significantly more expensive than their emerging markets counterparts. KT Corp (South Korea’s dominant fixed-line and second-largest mobile phone provider) is cheap on every single metric, including depressed earnings (when compared to other telecoms around the world). Can we imagine margins reverting? Can we imagine investors paying a decent multiple on their current earnings?

Charts reflect the growth of $1000 for two or more comparable companies and do NOT reflect the performance of any particular stock within any Kopernik portfolio.

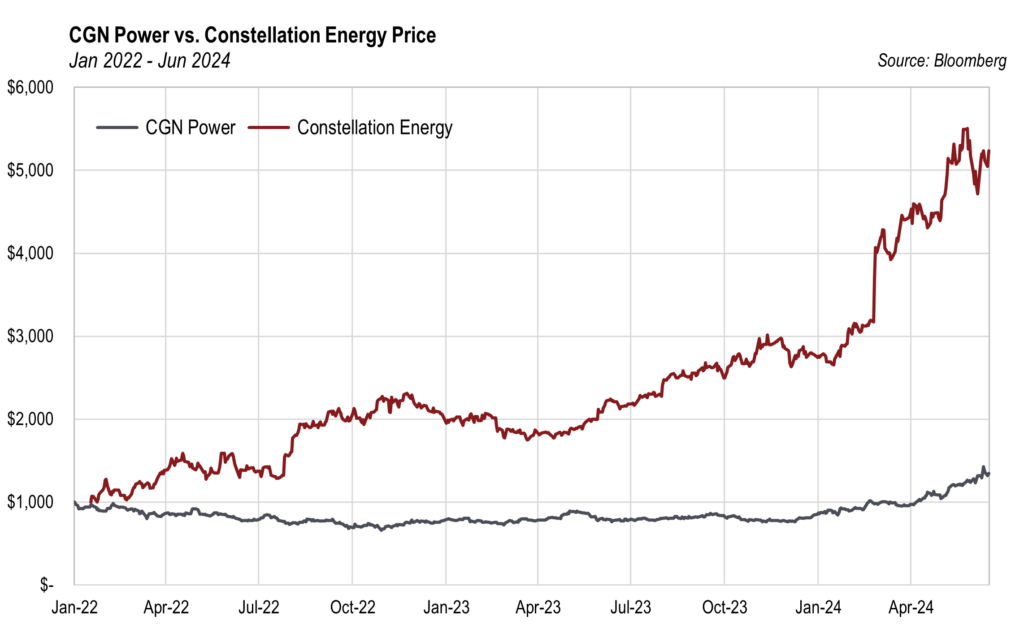

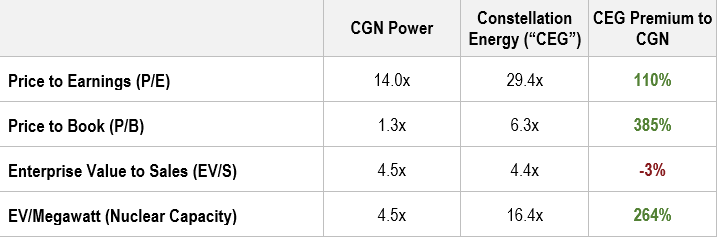

What if clean, cheap, carbon-free power in China was the same price as in the U.S.?

Nuclear power is a cheap and cleaner form of energy that is essential for a broad energy transition. Nuclear utilities have found themselves back in society’s good graces as the globe aims for greenhouse gas free electricity. CGN Power is a leading Chinese nuclear power company, and, even though it has newer, more modern nuclear plants, it trades at a sizeable discount to its peers in the U.S. What if the market assumed CGN was worth even half of Constellation Energy? The price gap between a joule of nuclear power in the U.S. and a joule of nuclear power in China appears to be narrowing; CGN has performed strongly recently and is now approaching our estimate of its risk-adjusted intrinsic value. Time will tell.

Charts reflect the growth of $1000 for two or more comparable companies and do NOT reflect the performance of any particular stock within any Kopernik portfolio.

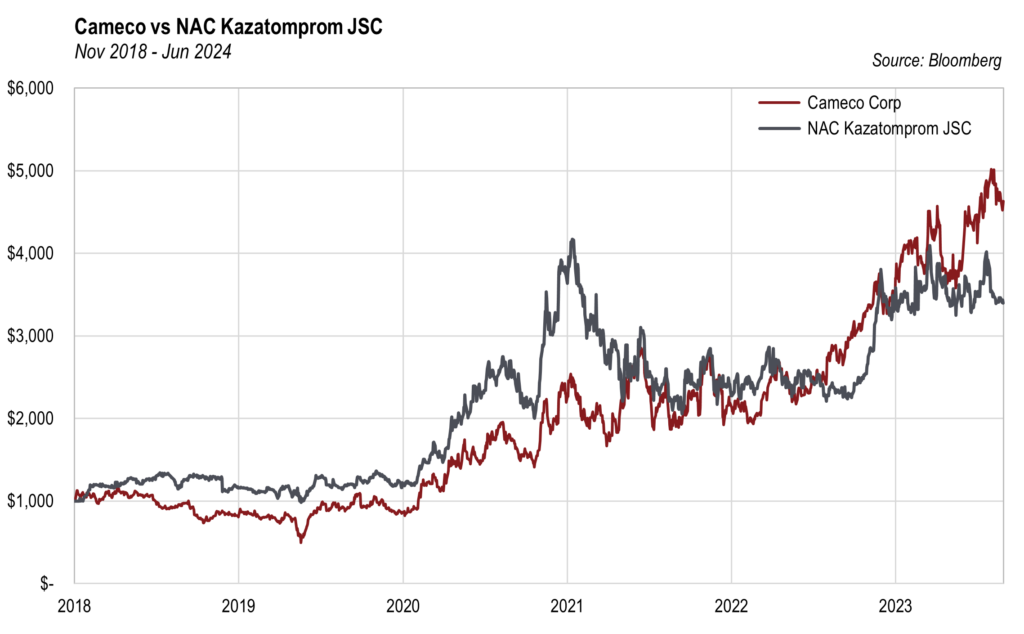

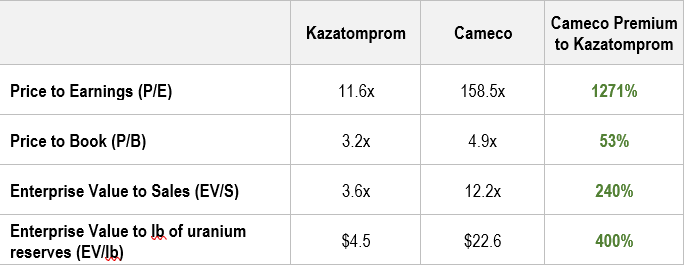

Kazatomprom is the world’s largest uranium producer; as the uranium price has risen and many miners have followed suit, Kazatomprom continues to trade at a discount. What if uranium in Kazakhstan traded like uranium in Canada? If many are thinking this is a stretch, it is worth pointing out that Kazatomprom traded at a healthy premium to Cameco as recently as 2021.

Charts reflect the growth of $1000 for two or more comparable companies and do NOT reflect the performance of any particular stock within any Kopernik portfolio.

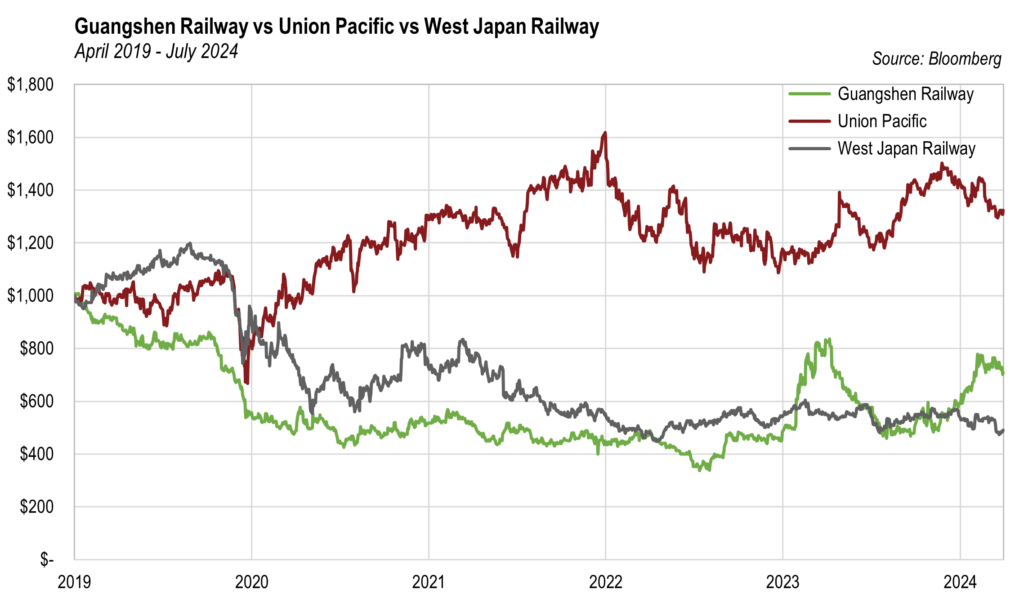

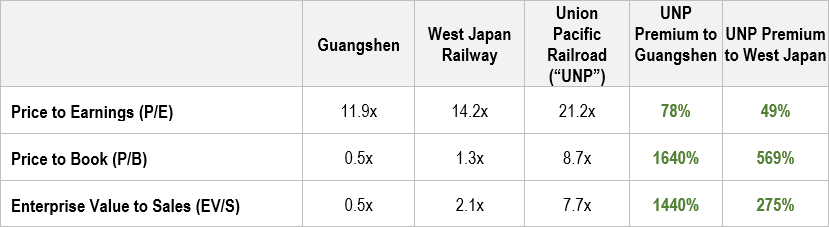

What if railroads elsewhere in the world began to trade closer to railroads in the U.S.?

Railroads in emerging and some developed markets trade at large discounts to railroads in the U.S. In China, Guangshen operates the Shenzhen-Guangzhou-Pingshi railway, which runs for 300 miles and connects the three largest population centers in Southern China (Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong). Railroads in Japan are world-class and provide some of the fastest, most efficient transportation in the world. Millions of people ride these trains every year. West Japan Railway operates the portion of Japan’s nation-wide railway network located on the western half of the island of Honshu and the northern tip of the island of Kyushu, including the cities of Osaka, Kyoto, Hiroshima, and Hakata. What if railroads outside of the U.S. began to approach the valuations of railroads in the U.S.?

Charts reflect the growth of $1000 for two or more comparable companies and do NOT reflect the performance of any particular stock within any Kopernik portfolio.

Conclusion

We live in an uncertain world where change is inevitable. That change is likely to be dramatic, accentuated by rapid technological advances, easy monetary policy, reckless fiscal policy, changing norms, historically-high valuations, and the fact that long periods of stability sow the seeds of future instability. These changes could be utopian or dystopian in nature.

Fortunately for active investors, the crowd’s behavioral heuristics have led to massive market inefficiencies. Many securities have been underpriced, leading to the likelihood of very positively asymmetric returns in the future. This seems like an inopportune time, in our opinion, to forgo choice, putting one’s portfolio into securities that are highly correlated to interest rates, or to one particular country, or heavily weighted towards expensive industries, requiring a “Goldilocks future.”

People understand that they should insure their house or their car. How much more important is to insure their nest egg? Fortunately, unlike homeowners insurance, financial insurance is seemingly unpopular and underpriced. Optionality is about choices and different paths to protect your investments and earn attractive returns. Building an anti-fragile portfolio via opportunities with mispriced optionality seems, in our opinion, to be the most reasonable path forward.

As always, thank you for your continued support.

Dave Iben, CFA

CIO, Lead Portfolio Manager

Alissa Corcoran, CFA

Deputy CIO, Portfolio Manager, Director of Research

Mary Bracy

Managing Editor – Investment Communications

July 2024

- The depiction in this chart of an S&P 500 put option is a hypothetical projection and Kopernik does not guarantee that the depicted scenario will occur at any time in the future. This hypothetical projection is shown for illustrative purposes only and does not reflect actual trading results. Future investments in put options may be made under materially different economic conditions, in different put options, using different investment strategies and, as a result, may differ significantly from the results portrayed. It is possible that the markets or the asset will perform better or worse than shown in the projections; that the actual results of an investor who invests in the manner these projections suggest will be better or worse than the projections; and that an investor may lose money by investing. Although the information obtained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, its accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Due to these limitations, investors should not make decisions to invest based solely on this information ↩︎

- The VIX Index is a financial benchmark designed to be an up-to-the-minute market estimate of the expected volatility of the S&P 500 Index and is calculated by using the midpoint of real-time S&P 500 option bid/ask quotes ↩︎

- GSMA, The State of Mobile Internet Connectivity Report 2023 ↩︎

Important Information and Disclosures

The information presented herein is proprietary to Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is not to be reproduced in whole or in part or used for any purpose except as authorized by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell any product or service to which this information may relate.

This letter may contain forward-looking statements. Use of words such as “believe,” “intend,” “expect,” anticipate,” “project,” “estimate,” “predict,” “is confident,” “has confidence,” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are not historical facts and are based on current observations, beliefs, assumptions, expectations, estimates, and projections. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to risks, uncertainties and other factors, some of which are beyond our control and are difficult to predict. As a result, actual results could differ materially from those expressed, implied or forecasted in the forward-looking statements.

Please consider all risks carefully before investing. Investments in a Kopernik strategy are subject to certain risks such as market, investment style, interest rate, deflation, and illiquidity risk. Investments in small and mid-capitalization companies also involve greater risk and portfolio price volatility than investments in larger capitalization stocks. Investing in non-U.S. markets, including emerging and frontier markets, involves certain additional risks, including potential currency fluctuations and controls, restrictions on foreign investments, less governmental supervision and regulation, less liquidity, less disclosure, and the potential for market volatility, expropriation, confiscatory taxation, and social, economic and political instability. Investments in energy and natural resources companies are especially affected by developments in the commodities markets, the supply of and demand for specific resources, raw materials, products and services, the price of oil and gas, exploration and production spending, government regulation, economic conditions, international political developments, energy conservation efforts and the success of exploration projects.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. There can be no assurance that a strategy will achieve its stated objectives. Equity funds are subject generally to market, market sector, market liquidity, issuer, and investment style risks, among other factors, to varying degrees, all of which are more fully described in the fund’s prospectus. Investments in foreign securities may underperform and may be more volatile than comparable U.S. securities because of the risks involving foreign economies and markets, foreign political systems, foreign regulatory standards, foreign currencies and taxes. Investments in foreign and emerging markets present additional risks, such as increased volatility and lower trading volume.

The holdings discussed in this piece should not be considered recommendations to purchase or sell a particular security. It should not be assumed that securities bought or sold in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of the securities in this portfolio. Current and future portfolio holdings are subject to risk.