Mining (Oct 2024)

“The secret to investing is to figure out the value of something – and then to pay a lot less.”

– Joel Greenblatt

Mining is an unpopular industry and is unpopular for very valid reasons. Management teams are prone to allocate capital pro-cyclically, destroying vast amounts of capital. Governments take advantage of the fact that companies cannot move a mine out of the country. And, operationally, mining is a difficult business. Many investors have been burned in the past, and vow never to get burned again, no matter the discount.

People are prone to hyperbole and exaggeration, frequently repeating phrases like “never” and “absolutely not.” Our philosophy discourages this binary thinking. The question is not “should we own this?” but “at what price is owning this worthwhile?” Emerging markets, unpopular industries, places with unfamiliar or challenging geopolitical situations – all these present specific challenges and lead to deep discounts and substantial bargains, creating the potential for outsized future gains. We’ll discuss how misanalysis further adds to the compelling values within this space.

This white paper (an update of our 2020 mining paper) explains how we value mining companies and why we currently prefer to own the mining companies, risks attached, to the physical commodities that underpin them. Pertaining to mining companies today, we see this binary thought process as extreme – an extreme that we are taking advantage of.

Not If, but How Much

There is a price for everything. Kopernik believes that investments should only be made once a reasonable estimate of a stock’s intrinsic value has been calculated. This process always begins with an analysis of the industry, including development of our proprietary industry templates. We analyze supply, demand, Porter’s Five Forces, material risks, primary valuation metrics, and key factors that will enhance a business’ ability to succeed within the industry. These factors differ from industry to industry; for example, some valuation metrics may be suitable for one industry but entirely inappropriate for another. In the case of mining, due to scarcity, the single most important driver is ownership of the material being mined. Usually, this means the more of the material, the better. Large deposits have the advantage of being able to produce over a full cycle (or, hopefully, much longer). Because mining is a scale business, size matters.

The most common way to value resource companies is net asset value (NAV) which usually means estimating five factors: the size of the resource, the speed at which the resource will be mined, the cost to mine the resource, the price of the commodity when it is mined, and the appropriate cost of capital over that time period. We believe estimating the future is a fool’s errand. Mining comes with a host of unknowns.

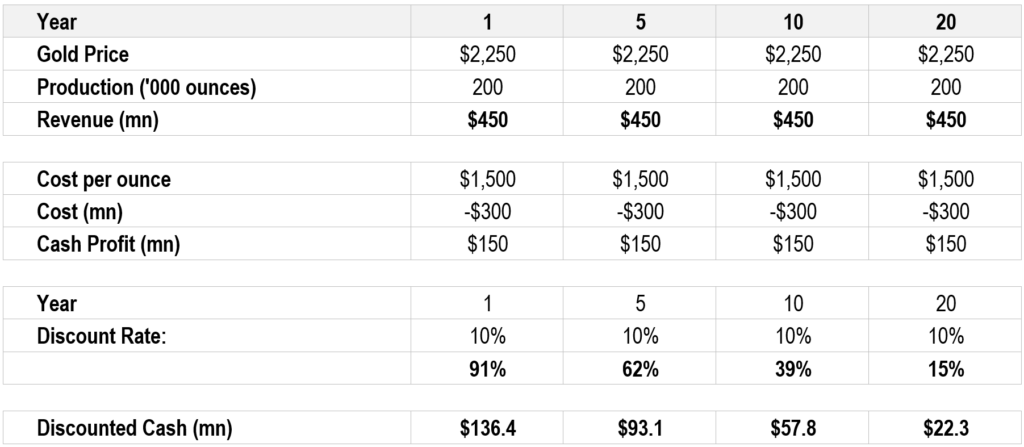

We have written extensively about the problems of discounting cash flows in a world of interest rate suppression, but it is worth a quick review.

“Time is what we want most, but what we use worst.”

-William Penn

As the theory of the time value of money states, the money you hold now is worth more than the money you’ll hold in the future because of its potential earning capacity. We concur. If you have $5 today, it is worth more than the exact same $5 a year from now, because you could invest it and earn returns over the 12 months between now and next year. Therefore, of course you would prefer the $5 now.

Discounted cash flow (DCF) models employ this theory to derive the value of a business, and many investors have been very successful using this technique. We argue, however, that DCF models have lost much of their effectiveness due to central bank manipulation. The central banks have subverted the market interest rate used to determine the discount rate. This has caused significant mal investment, which is impacting the cash flows that are being discounted. While they are highly appropriate for financial securities like bonds, where steady cash flows are expected, DCF models are a particularly poor tool for valuing companies that have volatile cash flow. After a quick discussion of the challenges of using DCF models, we’ll move on to the more important subject of the widespread misapplication of the DCF model, seemingly pertaining only to commodity-based industries.

A hypothetical example is helpful: an investor is given the choice between Company A, a gold mining company that is in production and has 10 years’ worth of resources to mine or Company B, a gold mining company that is estimated to start production 5 years from now but has 20 years’ worth of resources once the deposit becomes a mine. At the same time, the price of gold is reflecting a lack of demand in the market, and it may take time for prices to recover, but supply/demand and incentive price analysis suggests that it will recover to a price that is double current prices. Which company should the investor prefer? Using a DCF model, and a typical discount rate of 10%, investors would prefer Company A since a DCF model of distant cash flows would yield a very low value.

We believe this is faulty logic. There are several key flaws to the DCF model, all related to time:

- Time is the enemy of DCF models; depending on the discount rate, a DCF effectively gives very little value after year 20. This penalizes long-lived mines. We pose the question: If a company is going to go through the trouble of building a mine (not an easy feat), should we be indifferent if that mine operates for 20 years or 100 years? The easy answer is no, yet the DCF makes scant distinction.

- It is impossible to predict commodity cycles. There is a common saying in mining: “Mines earn 80% of their cash flow 20% of the time.” In a DCF model, the timing determines the outcome. If the timing is off, so is the outcome. Further, investors typically erroneously extrapolate current low prices into the future, falling victim to the psychology of cyclical markets.

- Most people will agree that gold is an excellent store of value. This leads us to the most important point that we wish to convey in this piece – that when the DCF model is applied to a real asset, investors have “flipped it upside down,” implying that gold (and other commodities) will lose value relative to dollars. Thousands of years of history suggest that it is the reverse that is true: fiat currency loses value relative to real assets. A gold coin today is highly likely to maintain its purchasing power in 10 years, 15 years, 100 years. Tremendous opportunities are created when others use a model that says that commodities pulled out of the earth today can be sold for a higher price than will be available if it is pulled out of the ground in 20 years. History and logic make clear that fiat currencies lose value relative to goods and services, not the other way around. It is worth taking note of the fact that when modeling virtually every industry, other than resources, analysts assume a price that rises over time.

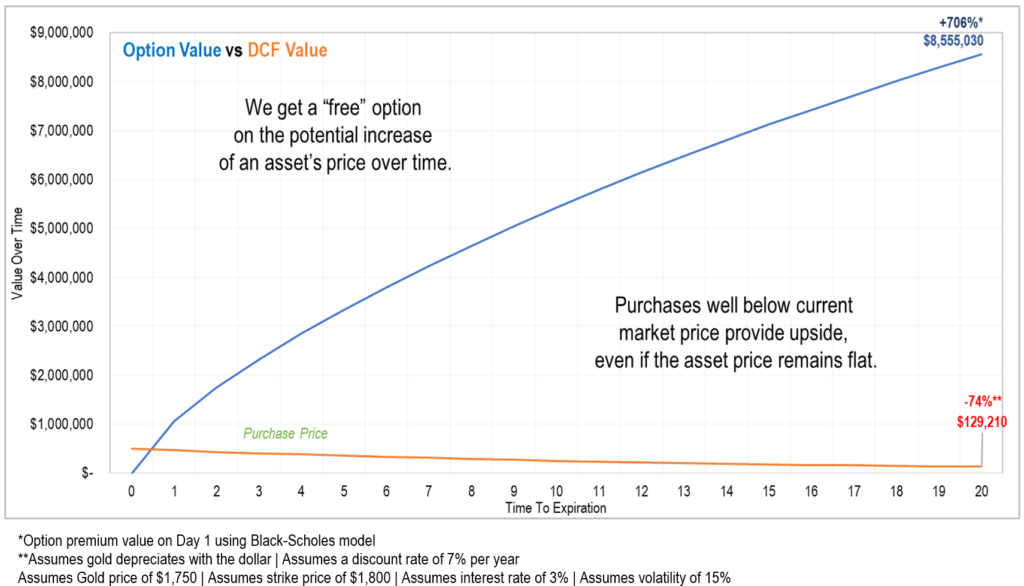

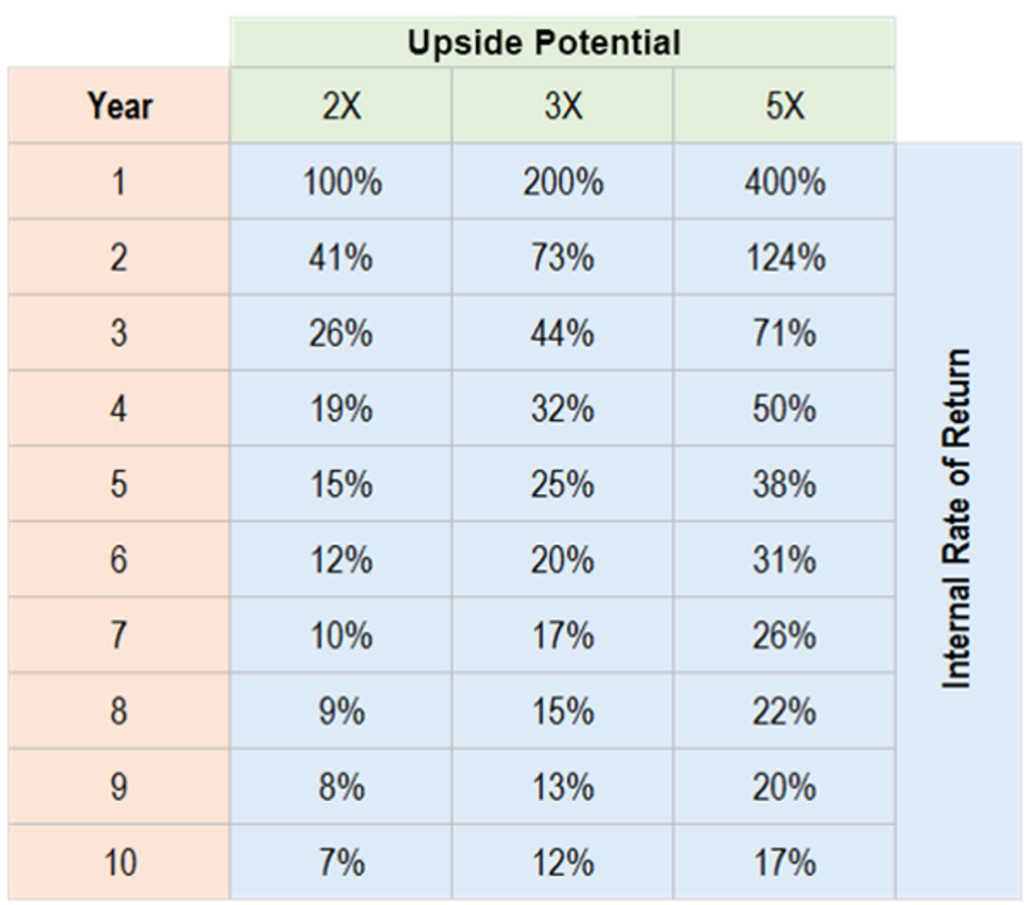

When dealing with underpriced goods, time is the investor’s friend. The longer the timeframe, the more likely prices are to revert to their intrinsic value. We often tell investors, parroting Rick Rule, that the last thing we would want a commodities company to do is extract all their material during the bad times, eventually being left with a hole in the ground where the resources once were when the good times come. For this reason, we prefer to include optionality-based models. To fully appreciate the difference between a DCF-based approach and an optionality-based approach, please refer to the graph below.

Additionally, it is easy to put less import on time when central banks around the world have repressed interest rates to artificially low levels and suggest that they will continue to do so indefinitely. It was much easier to wait for capital to be returned when a 10-year bond yielded less than 1%. At the current 4.2% yield, it is a little harder, however the upside that we continue to expect for real asset companies is much higher than the rate of inflation, over the long term. Patience is justified.

Our Approach

As mentioned, we look at many valuation metrics when performing analysis. But given the flaws of using DCF models in an era of interest rate suppression combined with the specific peculiarities of the resource extraction businesses, it should be clear why we put little emphasis on it. When our approach is the most different from the mainstream is when we get most excited, because it is then when we have the largest opportunity for outsized gains.

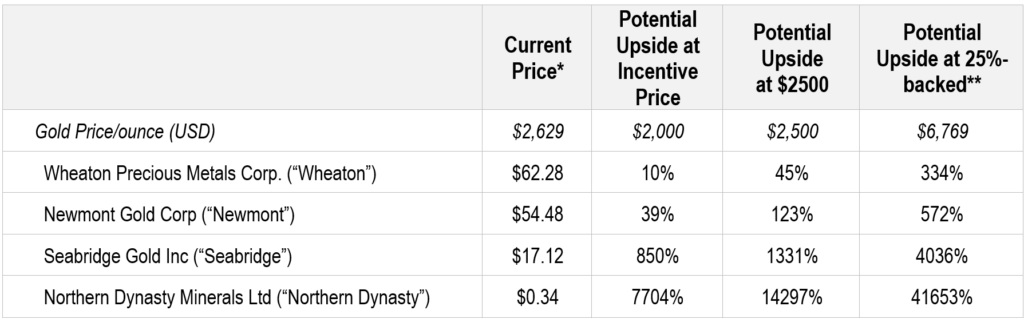

The table below shows the potential upside of four gold holdings at the incentive price for gold (the price at which we estimate it is economical to bring new incremental production online), the current gold price (around $2500/ounce as of August 2024), and the upside at 25% gold monetization (the arrangement under the Bretton Woods system). As the table shows, even at current prices, there is still substantial potential upside, particularly in producers and miners (less so in streamers/royalty companies). The figures shown are not risk-adjusted; our potential returns are lower, and our margins of safety are significantly larger for junior miners. For example:

- Wheaton (streaming company) represents claims on gold, largely protected from the aforementioned challenges inherent to mining. As such, we risk-adjust it moderately.

- Newmont (producing mining company) represents claims on gold with meaningful exposure to the many challenges facing miners. We accord a larger risk-adjustment factor to it.

- Seabridge (development-stage mining company) represents claims on gold with meaningful exposure to the challenges, plus the risks involved with getting a mine built. Therefore, we risk-adjust it heavily.

- Northern Dynasty (non-producing mining company) is similar to Seabridge, with the added headwind of trying to develop a misunderstood, and thus highly unpopular, property, meaning that the mine will be built years down the road, if ever. We risk-adjust by 85%.

**Represents potential upside if gold backed 25% of the U.S. monetary base (the arrangement under the Bretton Woods system).

Companies depicted in this chart are owned in portfolios managed by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. For illustrative purposes. Actual results may differ. Potential returns shown in this chart have not been achieved by any investors. This depiction is a hypothetical and Kopernik cannot guarantee the hypothetical scenario will occur. Future investments may be made under materially different economic conditions, in different securities, or using different investment strategies and, as a result, may differ significantly from the results portrayed. It is possible the markets, the assets, or an investor investing in this manner shown may perform worse than the hypothetical projections shown. The information used to create the hypothetical is believed to be reliable, but accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Investors should not rely on this information to make an investment decision. Scenarios assume a 50:1 ratio for silver, and 400:1 ratio for copper.

Importantly, we are 100% bottom-up investors. We like to figuratively “have our cake and eat it too,” by investing in stocks that have upside even if we are completely wrong on future fundamentals. They are undervalued at current prices and at incentive prices. While fundamentals argue for much higher prices, as bottom-up investors, Kopernik migrates toward stocks that are undervalued at incentive price, while gaining a “free” option on the probability that the upside scenarios actualize. We don’t pay for future expectations.

Opportunities Today: Why Miners?

Gold

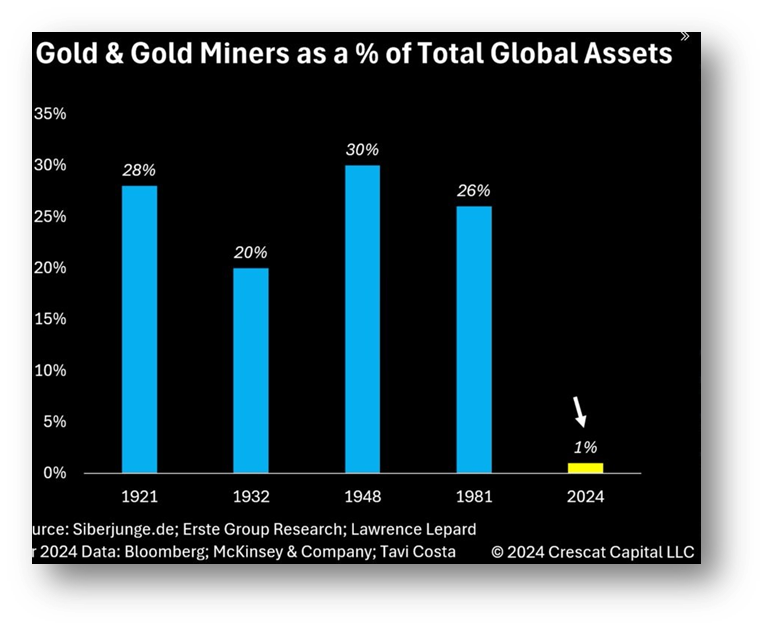

Because gold is scarce and hard to find, the key factor to success is ownership of gold, ideally lots of it. Finding a gold mine is incredibly difficult: only 1 out of 3,000 mineralized anomalies become mines1. Gold mining is a difficult business, yet priced very attractively, making it a prominent position within the Kopernik managed portfolios.

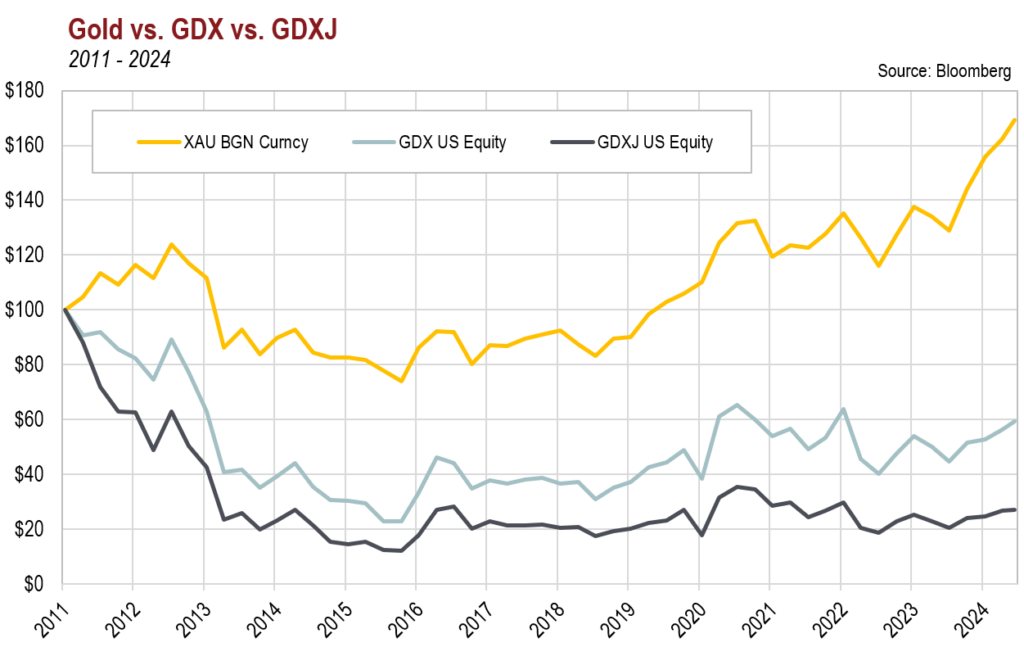

For more than a decade, the gold price has fared much better than that of the large miners (represented in the first chart below by the VanEck Vectors Gold Miners ETF – Ticker: GDX), which in turn have fared much better than smaller miners (represented by the VanEck Vectors Junior Gold Miners ETF – Ticker: GDXJ).

The gold price, after stagnating for many years, has begun to move higher as the effects of more than a decade of profligate central bank money printing migrate through the system. (For more on this, see our writings on the Cantillon effect, especially our 2023 commentary Proud Mary.) The miners have seemingly begun to catch up with the underlying commodity, but as the chart above (?) shows, there is still a lot of ground to make up. This presents numerous opportunities for investors.

Silver

Pure-play silver deposits are difficult to find, as silver is frequently mined as a byproduct of gold. Mining production has fallen in recent years, and demand has outstripped supply since 2021. Prices are extremely low; the gold to silver price ratio is currently 85:1. The fundamentals for silver are strong, and prices will need to rise to incentivize production. We anticipate that silver should trade at its long-term average ratio of 50:1, implying an outperformance from current prices. Many of the Kopernik managed portfolio’s gold companies have significant silver exposure as well. Seabridge’s KSM deposit has more than 400 million ounces of silver; Pueblo Viejo, a 60/40 joint venture between Barrick Gold Corp. and Newmont, has 150 million ounces.

Platinum Group Metals (PGMs)

Perhaps even more so than gold mining, PGM mining is a difficult business. Large new deposits are very difficult to find. Many mines are in regions with significant geopolitical risk—90% of the known world reserves of PGMs are located in South Africa, and that country accounts for 58% of global production. Corruption Watch, one of South Africa’s corruption watchdogs, claims that nearly 40% of the whistleblower reports it received in 2023 focused on the mining sector. Given the geology, PGM mining is very labor intensive, the mines are dangerous, and accidents happen with some regularity (although less often than in the past).

The risks are real and require diligent analysis and risk-adjustment. However, they do not make the industry uninvestable; indeed, there is a strong investment case for the PGMs, in our opinion. Investors must go where the platinum is.

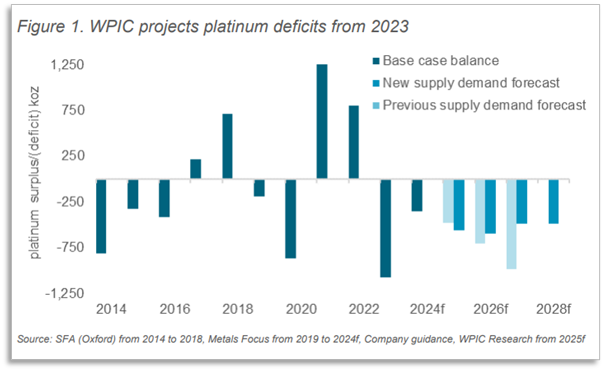

Unlike the gold price, which has reached all-time highs in recent months, platinum and palladium prices have continued to lag. As of this writing, platinum is down 52% from its 2008 high and 6% year-to-date. The palladium price has fared even worse, down 62% from its high in 2022 (and 15% year to date). Still, the investment case for these metals is compelling. Current prices are not high enough to incentivize mining companies to build. Most companies, in fact, are deferring sustaining capex. Eventually, prices can be expected to rise to the incentive price, timing unknown. The market is undersupplied currently, and deficits are projected to continue throughout much of the rest of the decade, according to industry groups.

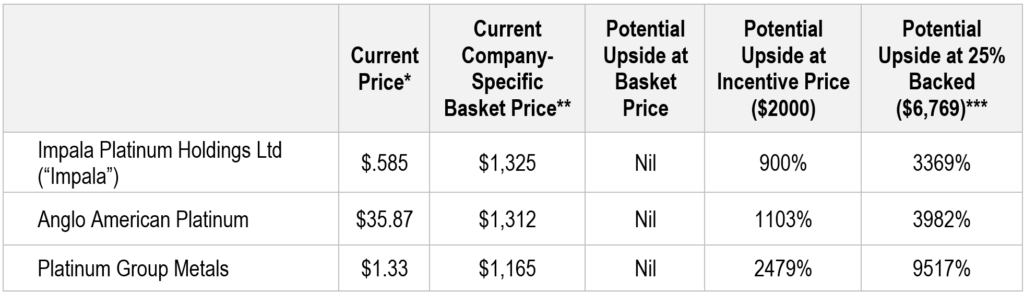

Similar to gold, platinum and palladium have money-like properties. They are scarce, divisible, noncorrosive, and attractive. As such, they have often traded at similar prices, if not premiums, to gold (see our precious metals whitepaper for more). The table below illustrates the upside potential we see in the Kopernik managed portfolio’s PGM producers. Platinum and palladium are often found together. These deposits also have rhodium and gold; thus, it is best to consider the basket PGM price when thinking about the incentive price. Further, we have included a scenario where precious metals may trade if valued as money.

**Basket price is company-specific and is calculated based on the percentage of gold, platinum, palladium, and rhodium within the orebody.

***Represents potential upside if gold backed 25% of the U.S. monetary base (the arrangement under the Bretton Woods system).

Companies depicted in this chart are owned in portfolios managed by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. For illustrative purposes. Actual results may differ. Potential returns shown in this chart have not been achieved by any investors. This depiction is hypothetical and Kopernik cannot guarantee the hypothetical scenario will occur. Future investments may be made under materially different economic conditions, in different securities, or using different investment strategies and, as a result, may differ significantly from the results portrayed. It is possible the markets, the assets, or an investor investing in this manner shown may perform worse than the hypothetical projections shown. The information used to create the hypothetical is believed to be reliable, but accuracy and completeness cannot be guaranteed. Investors should not rely on this information to make an investment decision.

Again, we should note that these scenarios are not risk-adjusted, and our potential returns could be lower. We require substantial margins of safety for each of these companies.

Uranium

In our last mining whitepaper, published in 2020, we argued that the dislocation between the miners and the commodities that they mine was just as pronounced in uranium as it was in gold. The uranium price languished between $20-$30/lb, and large miners had shuttered production at several mines. Uranium was decidedly unpopular, and the uranium miners were essentially radioactive.

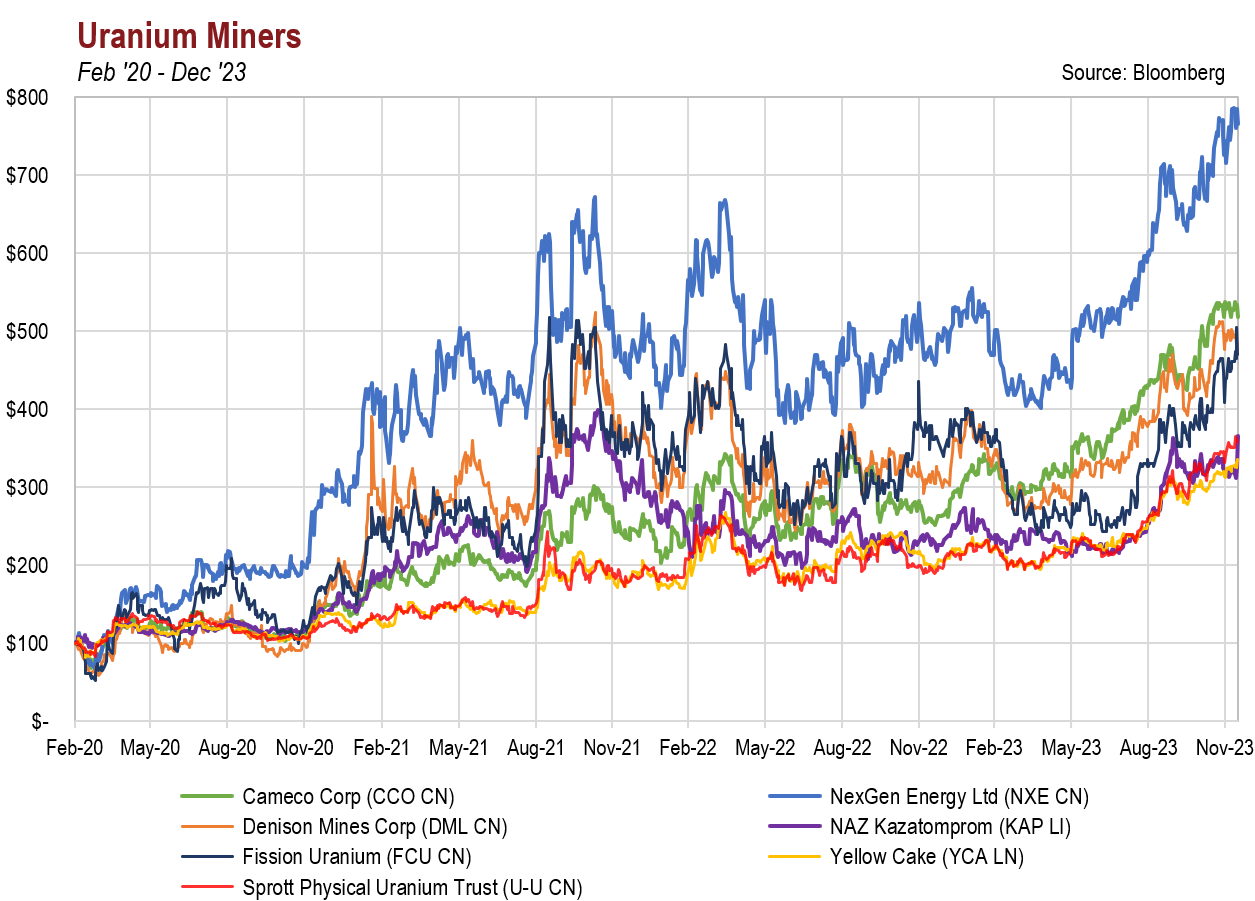

For 8 years between 2013-2021, we were decidedly not at the cool kids’ table, to borrow an analogy from our 2023 uranium whitepaper. Yet when popular opinion changed, it shifted rapidly and dramatically. This, combined with supply/demand dynamics that necessitated higher prices, has led to a surge in both the uranium spot price and the stock prices of the uranium miners.

We believe that one of Kopernik’s competitive advantages is behavioral – we are willing to buy unpopular stocks and, in doing so, are willing to accept career risk in order to lower the risk to the portfolio. Further, things can remain unpopular, and fundamentals can stay dislocated for an uncomfortably long period of time. As discussed earlier, one can afford to be patient when the potential upside is significant. Even though our investors had to wait 8 years for uranium to turn, we made substantial returns on many of our uranium holdings. Uranium is one example of how staying the course, and sticking to our disciplined research process, paid off.

The uranium spot price went from the mid-$20s/lb at the time of our 2020 whitepaper to roughly $85/lb today (peaking at over $100/lb. in January 2024). Stock prices went up significantly, as the chart below shows. Exploration companies sitting on large reserves went up the most: NexGen Energy Ltd, from bottom to top, went up 13x; Fission Uranium Corp went up 10x; and Denison Mines Corp went up 11x.

All other companies depicted in this chart are owned by portfolios managed by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC.

Chart does not reflect the returns of these particular holdings in a Kopernik managed portfolio.

Like what we see in gold miners (where the market is undervaluing non-producing miners sitting on large reserves), the non-producing uranium miners had the most optionality to higher uranium prices. In our opinion, other miners are well-positioned to follow a similar path.

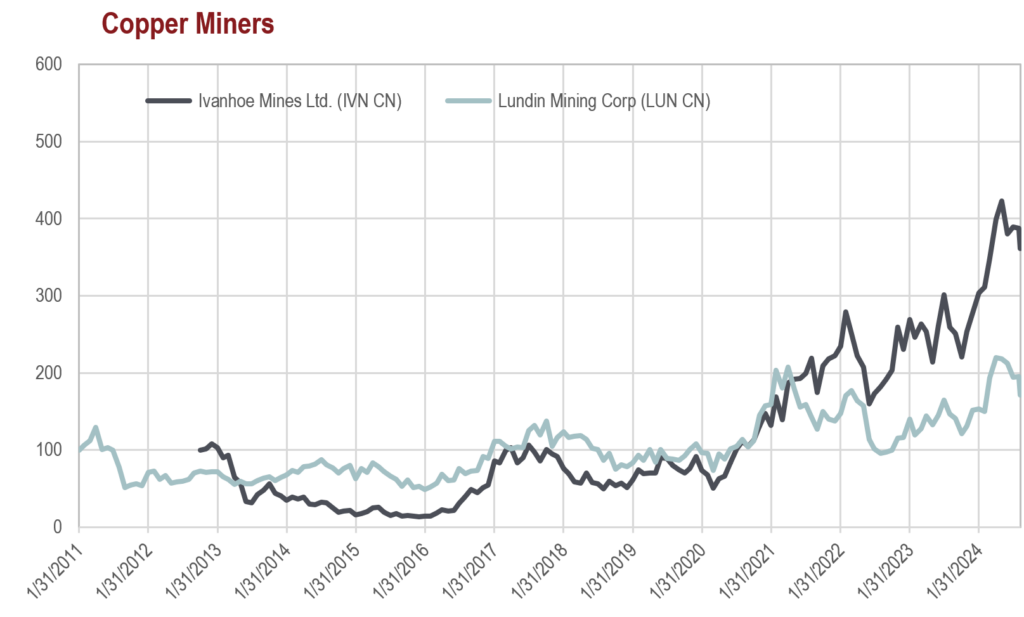

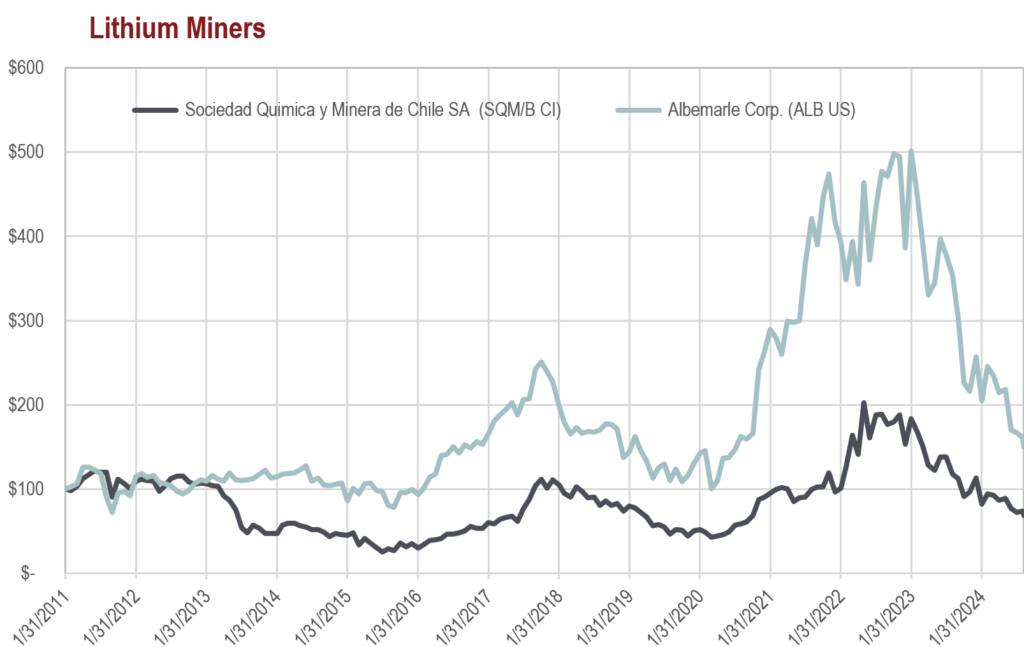

Copper and Lithium

We have been invested in copper companies for many years; many of the portfolio’s copper miners have approached their risk-adjusted values, and we have trimmed or eliminated the positions accordingly (more on that process below). Lithium companies are recent additions. The future demand scenarios for lithium are uncertain, and the ease or difficulty of bringing on new supply is uncertain. That being said, there were uncertainties when lithium was north of $80,000 per ton. Now, lithium is seemingly below the incentive price and below the marginal cost of production. Mines are shutting down and plans to build projects are being delayed. These are ultimately bullish signs for the lithium price and companies that own low cost, high-quality lithium deposits.

Unlike uranium, where the price languished at levels too low to sustain production for many years before rapidly rising to its incentive price, copper and lithium prices have see-sawed up and down, frequently alternating between extreme highs and lows as Mr. Market deemed them “ESG-unfriendly metals” before changing their minds to “ESG-friendly metals” and then enduring the resultant overproduction that sent prices back down. Lithium, in particular, has had wild fluctuations, going up more than 1300% between 2020-2022 before falling back to previous levels.

The prices of the miners have fluctuated as well:

Ivanhoe Mines IPO date 10/17/2012.

Chart does not reflect the returns of these particular holdings in a Kopernik managed portfolio.

As you have heard us say before, Kopernik views volatility as opportunity. As active managers, we take advantage of volatility to add and trim holdings, eliminating positions as they approach our estimate of their risk-adjusted intrinsic value.

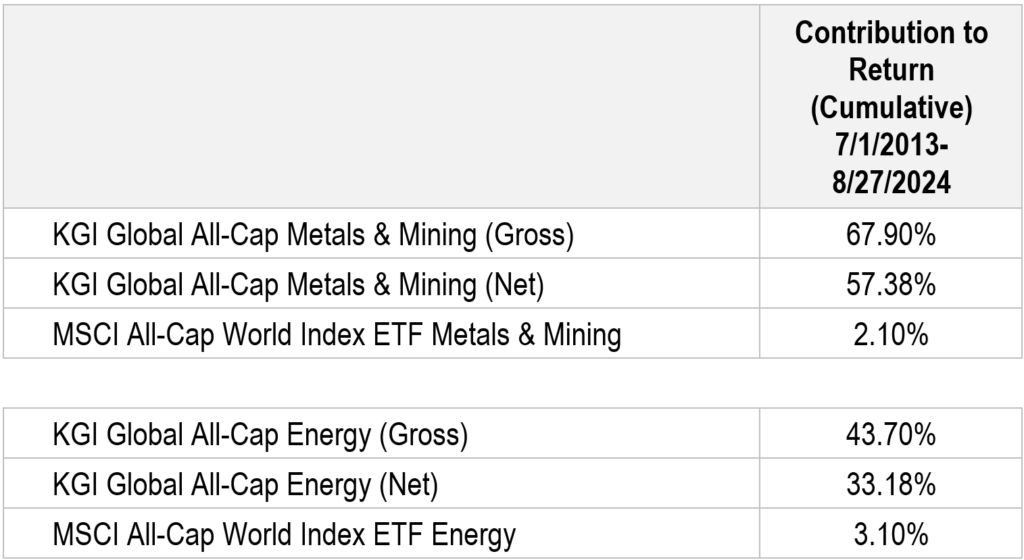

By using volatility to our advantage and allocating to the companies with the highest upside, we have seen significant outperformance in the Kopernik portfolio’s metals & mining stocks vs contributions by metals & mining to the MSCI All-Cap World Index benchmark. Energy stocks have seen a similar outsized contribution. As we discussed above, uranium miners were an area where we waited many years for the thesis to play out; being patient allowed us to take advantage of a massive market inefficiency.

representative account that we believe is reflective of the strategy.

Perceptions of Risk

While the upside potential for the miners is tremendous, it is imperative to consider the substantial risk inherent to mining. Kopernik views investment risk as the possibility of a permanent loss of capital. Some risks are systemic; with miners, the biggest challenge comes from business risks. Unlike systemic risks, business risks can be diversified away. It is extremely important to diversify across many different management teams, governments, currencies, geologies, geographies, chemistries, and companies. The market currently gives ample opportunity to do so, without sacrificing quality or standards. This is what we have done and encourage others to do.

No analysis of mining companies can be complete without addressing the formidable obstacles that they face. Management teams have collectively earned their reputation as destroyers of capital. They have a history of buying high, selling low, committing capital at inopportune times, diluting shareholders through serial stock issuance, options and warrants, and placing “growth” over economics. Geopolitical risk is rising, as it is for most industries in recent years, and is higher for miners as most countries have reevaluated the idea of letting foreigners extract their valuable resources without demanding a meaningful share of the economics. Also, due in part to a poor ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) track record, many countries have arguably swung from one extreme to the other in terms of their demands for mining companies. On top of this, costs are rising as the easy-to-mine resources have been mined. Remaining reserves often now reside on mountains, under glaciers, in remote deserts, deep in the earth, and/or in politically unfriendly locales. The chemistry, engineering, and geology have become increasingly complex. Stocks tend to be volatile, and many are in emerging and frontier markets. There are reasons that most people won’t touch them.

However, volatility is not risk, and neither are stereotypes; simply because miners are stereotypically considered poorly run companies does not mean that all gold mining companies are. As Howard Marks so effectively points out, risk to some is different than risk to another. When those who can’t handle volatility dump those stocks to attractive levels, not only is the upside potential enhanced, but the risk becomes lower for those who view risk as the prospect of permanent loss of capital, as Kopernik does.

We have written before about the important subject of risk. One important point to reiterate is that if one substantially discounts to adjust for risk of an individual holding, a diversified portfolio of stocks which are risky on their own can be low risk. High positive asymmetry and diversification are the keys.

Management error is often a cyclical phenomenon. Management tends to get overly confident and throw caution to the wind at the top of the cycle. At the cyclical trough, they get overly cautious, sowing the seeds for the next upswing. With many commodities having recently suffered more than a dozen years of bear market, managements are generally being ultra-conservative. They are not tossing around capital. Few are investing at all. When the cycles eventually swing to the other extreme, prudent investors will be long gone.

To repeat, we utilize our fundamental, bottom-up research process and industry-tailored valuation metrics to find the best risk-adjusted investments, heavily discounting for the risks. While a producing company may require a 30-50% margin of safety, a development stage company may require a 50-70% margin of safety. One company in the Kopernik portfolio had a 90% margin of safety. In other words, in this instance, to compensate for potential risks, we would only invest at a price where the potential upside to our appraised value is ten times! When many stocks are going up, some substantially, a well-diversified portfolio can handle a few adversities and still provide attractive returns. Kopernik only invests in miners when the upside potential is significant, even after discounting the risks. The risk-adjusted upside potential currently is substantial. Many of the business specific risks are diversified away, and, as long-term investors, we are willing to be patient. We have shown the chart below elsewhere, but it is worth a reminder of the potential benefits of “weighting the wait.”

Conclusion

From a bottom-up standpoint, many commodities are vastly undervalued relative to history and to the price required to sustain production into the future. They arguably deserve a place in all portfolios. For those incorporating top-down factors such as unlimited sovereign borrowing and central bank currency issuance, the case becomes exponentially more persuasive. Physical holdings and/or holdings via ETFs or similar structures make a lot of sense. However, ownership of publicly traded owners/producers of resources currently offer much potential, even when heavily adjusted for risk.

Miners are fortunate to have control of certain resources and the tremendous optionality that comes with that. We believe that many companies in this industry are significantly underpriced because investors have grossly overreacted to legitimate concerns regarding the difficulty of mining, because they shun volatility and headline “risk,” and most importantly, because most investors have “flipped” their DCF models upside down, thereby affording the lowest valuations to long-lived resources, those most coveted within the industry. The risks that do exist can be managed through adjusting valuations and by diversifying them away across different management teams, governments, currencies, geologies, geographies, chemistries, and companies.

The magnitude of undervaluation of resource stocks tends to increase meaningfully with exposure to tough geographies, unpopular commodities, and especially with the duration of the expected production profile. As should be the case with all investments, the most important question to ask is: At what price do they become good investments? Fundamentals and history suggest that many mining stocks currently provide extraordinary investment opportunities. Inflation protection is an added bonus.

Investment Research Team

Kopernik Global Investors, LLC

October 2024

Important Information and Disclosures

The information presented herein is proprietary to Kopernik Global Investors, LLC. This material is not to be reproduced in whole or in part or used for any purpose except as authorized by Kopernik Global Investors, LLC (“Kopernik”). This material is for informational purposes only and should not be regarded as a recommendation or an offer to buy or sell any product or service to which this information may relate.

This letter may contain forward-looking statements. Use of words such was “believe”, “intend”, “expect”, anticipate”, “project”, “estimate”, “predict”, “is confident”, “has confidence” and similar expressions are intended to identify forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are not historical facts and are based on current observations, beliefs, assumptions, expectations, estimates, and projections. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and are subject to risks, uncertainties and other factors, some of which are beyond our control and are difficult to predict. As a result, actual results could differ materially from those expressed, implied or forecasted in the forward-looking statements.

Please consider all risks carefully before investing. Investments discussed are subject to certain risks such as market, investment style, interest rate, deflation, and illiquidity risk. Investments in small and mid-capitalization companies also involve greater risk and portfolio price volatility than investments in larger capitalization stocks. Investing in non-U.S. markets, including emerging and frontier markets, involves certain additional risks, including potential currency fluctuations and controls, restrictions on foreign investments, less governmental supervision and regulation, less liquidity, less disclosure, and the potential for market volatility, expropriation, confiscatory taxation, and social, economic and political instability. Investments in energy and natural resources companies are especially affected by developments in the commodities markets, the supply of and demand for specific resources, raw materials, products and services, the price of oil and gas, exploration and production spending, government regulation, economic conditions, international political developments, energy conservation efforts and the success of exploration projects.

Investing involves risk, including possible loss of principal. There can be no assurance that a strategy will achieve its stated objectives. Equity funds are subject generally to market, market sector, market liquidity, issuer, and investment style risks, among other factors, to varying degrees, all of which are more fully described in the fund’s prospectus. Investments in foreign securities may underperform and may be more volatile than comparable U.S. securities because of the risks involving foreign economies and markets, foreign political systems, foreign regulatory standards, foreign currencies and taxes. Investments in foreign and emerging markets present additional risks, such as increased volatility and lower trading volume.

The holdings discussed in this piece should not be considered recommendations to purchase or sell a particular security. It should not be assumed that securities bought or sold in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of the securities in a Kopernik portfolio. Kopernik and its clients as well as its related persons may (but do not necessarily) have financial interests in securities or issuers that are discussed.